On her path to a prestigious clerkship with the Supreme Court of Canada, Naiomi Metallic overcame many obstacles, including two fussy babies. Born near the Listuguj, Quebec reserve to a French-Canadian mother and a Mi’kmaq father, Metallic boarded a red-eye flight from Halifax to Ottawa for an early morning round of clerkship interviews in 2005.

“There was a baby near me on the plane who cried most of the way,” she recalls. “And the friends I stayed with in Ottawa had an infant who was sick. So I didn’t get much sleep.”

Undaunted, Metallic blazed through a rigorous interview process and ultimately landed a position with now-retired Supreme Court justice Michel Bastarache, who was recently appointed to administer the class-action sexual harassment lawsuit against the RCMP. In doing so, Metallic became the first known person of aboriginal heritage to secure a clerkship with the nation’s highest court.

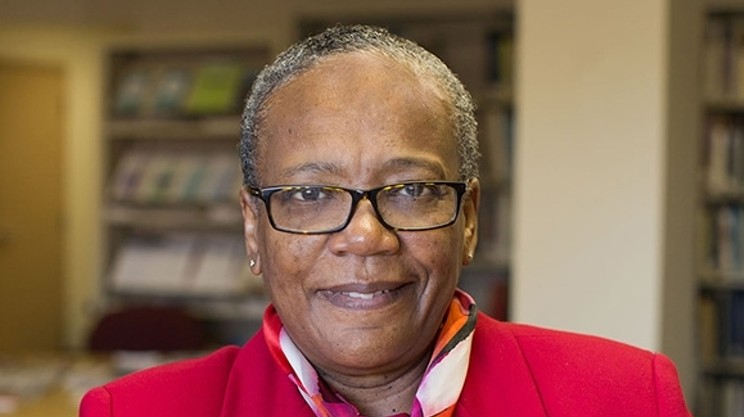

Today a tenure-track professor at the Schulich School of Law at Dalhousie, Metallic, 35, is poised to impact a generation of attorneys. Herself a Dal alumnus, she holds the university’s inaugural Chancellor’s Chair in Aboriginal Law and Policy. Dal officials recently celebrated Metallic’s landmark post (and Mi’kmaq History Month) with a festive reception for her at the law school. Back at her Dal office, Metallic sits at her desk across from a sleek, black leather sofa that she bought (secondhand) to provide a cozy resting place for her students. “Gotta have a comfy couch,” she says.

The office walls display a sign that reads “Pisgwa” (“welcome” in Mi’kmaq) and a walking stick that Metallic received, she says, “after winning a big case.”

She beams when discussing her upbringing on the Listuguj reserve (population 3,000) with two sisters. Her mother, Madeleine Morissette, toiled as a nurse. Her father Emmanuel, who passed away in 2008, was chief compiler of the Metallic Mi’kmaq—English Reference Dictionary that bears his surname and has been hailed as a milestone in aboriginal lexicography.

“My parents worked hard to give us opportunities,” says Metallic, noting that she was bused off-reserve to attend an English language school. “I took piano lessons, played basketball and volleyball. Of course, I met kids who thought of life on the rez as nothing but poverty and despair.”

An undergraduate English and philosophy major, Metallic says she envisioned a writing career and had “no intention whatsoever” of becoming an attorney. However, impressed by Metallic’s stellar grades, administrators at Dal’s Indigenous Blacks and Mi’kmaq Initiative (IB&M) encouraged her to apply to law school.

“From the beginning, Naiomi took on leadership roles,” says Michelle Williams, director of the IB&M program. “She was always very firm in her convictions and advocacy for marginalized groups.”

Still, Metallic says she felt like an “imposter” at the Supreme Court. “It was difficult to believe that I really belonged,” she explains. “I’d look around and think, ‘It can’t be little old me from a reserve, who has this important job.’” Metallic says she was especially grateful for the embrace of Madeleine Redfern, the first Inuk to clerk on the Supreme court and the current mayor of Iqaluit, Nunavut.

“I’d been at the court a little longer than Naiomi,” Redfern says. “We both saw the value in sharing our unique knowledge, experiences and perspectives as Indigenous clerks to our respective judges.”

“Madeleine bolstered my confidence in an environment where misconceptions about First Nations still exist,” Metallic says.

Speaking candidly about his own background, Justice Bastarache says he was surprised to learn of Metallic’s insecurities.

“As a law student, I was the only Acadian and felt...a bit intimidated by the group of students who were from the same prep schools and living like they had already made it, and had a large income to prove it,” he says. “I was clearly an outsider. Naiomi had a more difficult minority status than mine to cope with and surely felt she had to prove herself.”

In addition to teaching courses on Indigenous governance, Metallic (who also holds advance law degrees from Osgoode Hall Law School and the University of Ottawa) has crafted an ambitious plan designed to elevate Dal’s profile on Indigenous affairs. The strategy includes helping other Dal faculty incorporate First Nations content into their teaching, developing cultural immersion camps and organizing a conference on Indigenous languages.

Monisha Sebastian, a third-year law student, says that Metallic has prompted her to “think big” about her career.

“She’s shown me that I have numerous options as an attorney,” says Sebastian.

“And what I’ve learned in her class about Indigenous law will shape whatever path I choose.”

As Canada strives to address the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Metallic has much to offer as an accomplished, politically engaged attorney.

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” she says about prime minister Trudeau’s pledge to “reset” Indigenous relations.

In the meantime, she has a lot of work to do at Dalhousie, and with downtown law firm Burchells LLP where she was an associate attorney and will remain on staff as counsel.

Despite her hectic pace, Metallic makes little use of her office couch. Instead she “unwinds” by also working as a server at Picnic, a Dartmouth eatery owned by her chef husband.

“It’s the only time I get to see him,” she quips.