On a recent Sunday afternoon in May, Michelle Coffin’s doorbell rang. Leaving her apartment to answer it, she was surprised to find her upstairs neighbours already in the shared vestibule of their building. Just beyond them stood the Liberal MLA seeking re-election in her riding, Labi Kousoulis. Next to him, to bolster support, was federal Liberal MP Andy Fillmore.

It was a casual doorstop cold-call, par for the course in the campaigning run-up to a provincial election. But Kousoulis, Fillmore and the party volunteer who joined them that day must not have

Standing in the entryway, Coffin’s blood ran cold.

“I thought I was over it,” she says. “Then Labi ended up on my front door.”

Three years earlier, almost to the day, Michelle Coffin lay crumpled on her bedroom floor, trying in desperation to call out the open window of her south end apartment for someone, anyone, to call the police. But no one heard her, or no one heeded her call.

Her boyfriend, Kyley Harris, was standing over her, kicking her in the legs. Moments earlier, after hours of arguing over text and in person, Harris had raised his fists. “You want to fight?” he said. “I’ll fight.”

That’s when Coffin gave up. “I just stood there while he punched me.”

The unseasonably mild weather

“I hit my head on the treadmill on the way down,” she says blankly, pulling a long yellow sweater around her small frame while recalling the punch that felled her.

“I saw stars while I was falling.”

Eventually, she managed to stand up, grabbed her phone and dialled 911. She almost didn’t call. When she finally did, she hung up as the

“My boyfriend just assaulted me.”

Michelle Coffin hasn’t come forward with what happened to her until now. She didn’t want to

Nevertheless, a version of this story has been told many times over. Kyley Harris is fired from his job with the Liberal Party in 2014. He pleads guilty to assault. Several months later, he’s quietly rehired in a background role as a researcher and then—in the kickoff to May’s general election—Harris is promoted to the Liberal’s central campaign communications director.

It is two weeks later that Labi Kousoulis, the Liberal MLA incumbent in Halifax Citadel–Sable Island, arrives at Coffin’s door.

On that Sunday afternoon, when Coffin’s own MLA candidate explained to her, a victim of domestic violence, why her abuser, the man who punched her in the face and kicked her while she lay on the ground, deserved a second chance, she decided enough is enough.

She’s done with other people’s narratives. Michelle Coffin wants to tell her story.

“We’ve got two problems in this city,” a cop told her that night, back in 2014. They were both sitting in her apartment, waiting for paramedics to determine whether her nose and jaw were broken. “Drunk driving and domestic assault.”

Two days later, her nose still bleeding on-and-off, Coffin showed up at the hospital. She had a black eye, and a ball-shaped nub on her forehead—the remaining imprint of a fist.

“Who did this to you?” an emergency room doctor asked in concern.

At the time, Harris was

Harris would later plead guilty, receiving a conditional discharge and nine months probation.

Fast forward three years.

As the provincial election is called, Harris’ name shows up at the bottom of a press release announcing the Liberals’ campaign communications team. He’d been promoted, back into his old position as party spokesperson.

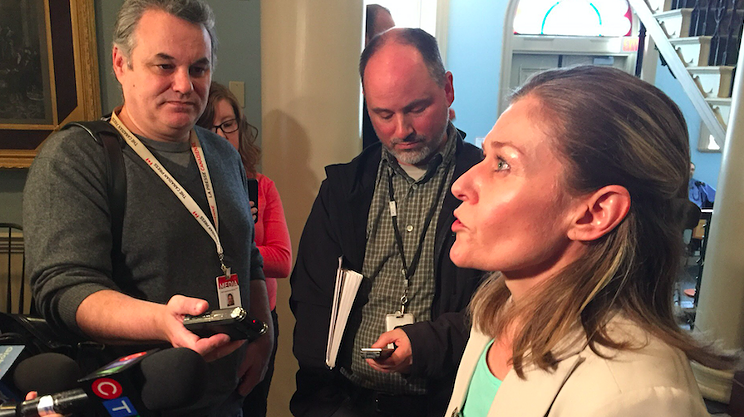

When The Coast first broke the news of his re-hiring, the Liberals and Harris refused to comment. A week later, after the story was picked up by other outlets and mentioned on social media by then-federal Tory leader Rona Ambrose, Harris offered his resignation. In a letter to the party, the communications director said he could not allow his colleagues and McNeil to continue to be punished for his actions.

Ironically, Harris’ job title was one Coffin herself once held. As a Liberal Party faithful, she was first brought on as a member of the communications team in 2001, when Conservative John Hamm was

“He was fast, and he was accurate,” Coffin grants, “and a good writer.”

A petite woman, with blonde hair and steely eyes, standing not higher than five feet tall, Coffin’s voice belies her physical stature: she speaks directly—punctuated with sharp questions, often asking for clarifications.

She came to politics naturally, growing up in Sydney where “the Liberal Party dominated.”

Barbara Emodi, a long-time caucus staffer with the NDP who has been sitting alongside Coffin on political panels for years, describes her as “highly reputable.” Progressive Conservative strategist and fellow pundit Chris Lydon agrees.

“She’s unflappable,” he says, highlighting Coffin’s strength and dry wit. “You have to have a combination of confidence and humility to survive in that racket...and obviously, it served her so well in that sphere.”

When the election was called, Coffin steeled herself. Because Harris was back in the news, she knew to expect her name and the story of the attack to resurface. She also knew—always the spin-buster—that the other parties might use it as leverage during the campaign.

“It’s an easy target,” she says with a shrug.

“What I hadn’t prepared for,” she adds more sternly, “was the Liberal candidate coming to my door.”

From her experience as a political insider, Coffin knew the paperwork a party will arm its candidates with when they’re out knocking on doors. The lists of names and corresponding addresses come attached to notes identifying previous party supporters and voters. So when the doorbell rang that Sunday afternoon, she was taken aback. She had never expected to hear from a Liberal candidate again. The conversation that followed would push her to break her silence.

She stood at the back of her apartment’s entryway, listening to Kousoulis and Fillmore answer her neighbours’ questions.

“My heart started beating out of my chest,” she recalls. “My hands were sweating.”

Something stirred in her. She decided to speak up.

“What are your views on domestic assault?” she asked, without identifying herself as either a former Liberal staffer or the woman attacked by Harris. “What are your views on violence against women?”

Kousoulis answered right away. Without mentioning a name, he reportedly said “that individual” is no longer in the position. The candidate went on to say that Harris struggled to find work after his sentencing, and McNeil had wanted to offer help.

“The premier called all of the women’s

Coffin’s neighbour, Corissa Gagnon, confirmed Coffin’s account of Kousoulis’ words.

Coffin concluded that Kousoulis either misspoke, was parroting a spoon-fed Liberal talking point, or was knowingly lying to her face.

Several domestic violence

“I can tell you our

The Liberals aren’t commenting on the matter further. Neither Kousoulis nor Fillmore responded to multiple requests to reach them with questions about the incident. David Jackson, spokesperson for McNeil, likewise didn’t respond to questions left for the premier. The Liberal Party, on behalf of Kousoulis, only offered a brief emailed statement.

“

Her own MLA candidate stood at her door and told a victim of domestic violence why her abuser, the man who punched her in the face and kicked her while she lay on the ground, deserved a second chance.

tweet this

“It’s still there,” Coffin says.

There were fights. When the fights became violent, Coffin says she fought back. On the night she called 911, buttons were popping off Harris’ shirt as Coffin pulled on it, struggling to make eye contact.

“I thought I could make him stop.”

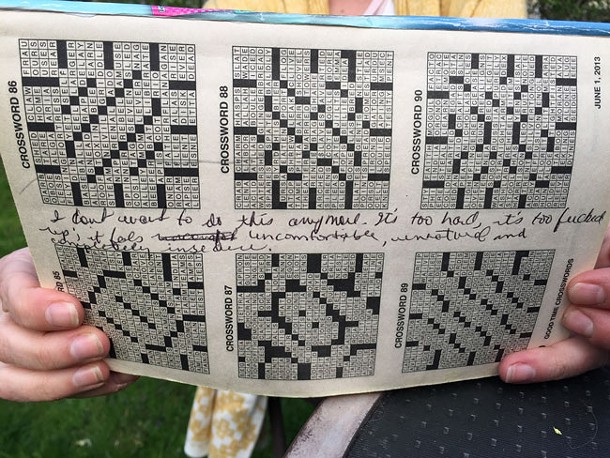

Many of the details of the attack on May 9,

“I tried and tried and tried to make things normal,” she says about the relationship, “to make things work.”

After two years, she was invested. They loved each other. She didn’t want to give up. She stayed, and she didn’t tell anyone what was going on.

Since the Ghomeshi trial, sexual violence has launched into a prominent national discussion—and deeper still, into the public consciousness. But some say domestic violence remains a hidden, lived tragedy.

In 2015, the Canadian Labour Congress and Western University released the results of a joint study on domestic violence in the workplace. It found that one-third (33.6 percent) of respondents reported experiencing violence from an intimate partner. The study was commissioned partially because of the lack of research on domestic violence across the country.

“We did this because there is almost no data on this issue in Canada,” the report reads.

An outdated trope is that stories like

Some groups are more vulnerable than others. According to a 2010 report from the NS department of justice, women aged 15-24 and those with lower incomes are more likely to experience violence from their partners. Indigenous women in Canada have spousal assault rates three-and-a-half times greater than non-Indigenous women. But the research also shows that, like cancer, intimate partner violence doesn’t discriminate.

To detractors who may doubt the prevalence of these crimes, let’s take a look at the statistics. Eight percent of women in Nova Scotia (or about 21,000 individuals) have experienced physical violence from their partner, according to the DOJ’s numbers. But for the sake of clarity, let’s narrow that focus. We’ll just stick with the Liberals. Instead of just looking at party members or elected officials, let’s narrow the focus again. There were six women in

In the Liberals’ 2017 campaign platform, the government commits to “ending gender-based violence” upon re-election.

“We must also work to prevent domestic violence from happening in the first place,” it reads.

“Our plan will create a continuum of programs to address domestic violence, focused on primary prevention and providing victims support to rebuild their lives.”

Noble goals, but undercut by what sociologist Ardath Whynacht says is a problematic message to survivors, sent by the former government’s decision to rehire Harris.

“Stephen McNeil has essentially told every victim of domestic violence that if their partner says they’re sorry, you should let them back in the door,” says Whynacht. “That’s scary.”

When personal accounts of domestic assault—or the latest term, adopted by McNeil’s government, of “intimate partner violence”—are made public, either through the courts, media or social media, the reactions are increasingly predictable.

One is of support. Victims come forward to acknowledge and reinforce each other. There’s an evolving language, even a movement around praising courage among those who speak out. The word “victim” is being replaced with “

The other school of thought is delivered in a torrent of judgements. These women somehow brought it on themselves. It’s the spurned ex-girlfriend narrative. The “crazy bitch” write-off.

Coffin spent three years following the attack trying to keep her name out of the media—an attempt which, despite rigorous efforts, failed repeatedly.

“I don’t believe that the most intimate relationship that I was in...was anyone else’s business,” she says, “and I didn’t want it out there for public consumption.”

Federal legislation allowing victims of intimate partner violence to request a publication ban in court cases has since passed. But it came a year too late for Coffin.

She repeatedly asked journalists, even some she knew from the legislature, to keep her name out of the news. It didn’t work.

To understand Coffin’s resistance in being named by the media one need only look to her career. Beyond the personal ramifications are the impacts on Coffin’s professional life. She isn’t invisible to the public eye. A part-time professor, she teaches in the political science departments at Saint Mary’s and Dalhousie University, where she was voted Best Teacher in 2014 by the Dal Student Union. She’s been providing political commentary to media outlets for years, including as a panellist on CBC Radio’s “Spinbusters” segment (next to

“Nothing for me professionally could change,” she says. The bills weren’t going to stop just because she had been assaulted. “I had to carry on.”

The deeper irony is that the assault is the exact kind of story Coffin would’ve been managing from the inside in her previous job as communications director. Strategizing potentially unsavoury and even damaging stories, and coming up with plans on how to frame them to the media, was part of her role.

While Coffin had

“I haven’t been back to the Legislature in three years,” she says, with longing.

After the incident made the news, word got around the party fast. Coffin claims there was an abrupt isolation that came with it.

“I worked for Stephen. I was his first director of communications. I know half of cabinet...Never once has any Liberal contacted me. Not one.”

Waiting to appear on her regular “Spinbusters” panel at the CBC Radio studios on Mumford Road recently, a Liberal cabinet minister Coffin knew passed through the hallway where the panellists were waiting.

“He pretended I didn’t exist,” she says.

It’s the kind of interaction her fellow “Spinbusters” have witnessed.

“The fact is, I’ve seen her being

Lydon says he knows of friends among the New Democrats and Tories who reached out to Coffin when news of the attack broke. But among Liberals, he says, it was as if she had “vanished.” He still can’t make sense of their silence.

“Perhaps institutionally, they picked the person they wanted to defend, and the person they wanted to cut loose.”

“People are embarrassed. People avert their eyes,” she says. “They don’t want to acknowledge it happened.”

It can happen to anyone, says

“People need to understand the price you pay when the old boys’ network closes ranks against you.”

The experience has been duplicated over and over again for Coffin, even outside the legislature; running into old colleagues at the grocery store, watching them turn away from her. She says it’s left an enormous impact.

“I felt very alone.”

About a week after Harris was sentenced in the spring of 2015, Coffin came face to face with some of her estranged colleagues at a mutual friend’s wedding. One of them was then-justice minister Diana Whalen. They talked about the attack. Coffin claims Whalen told her the things had been harder for Harris since “Kyley took the brunt of it.”

Whalen denies that version of events. While she can’t recall the conversation exactly, Whalen tells The Coast she “can’t imagine saying that.” She thinks Coffin either misheard her or remembers events differently. The interaction was “unpleasant,” Whalen admits. It was noisy and chaotic.

“I was trying to calm her down,” says Whalen.

There’s a perception that women in politics stick together. The reality is more complicated.

“I don’t know Kyley in any close way, so I don’t know any of the circumstances around what happened,” says Whalen. But, “if he admitted he did wrong, he did the right thing.”

The self-described feminist and former MLA says when she was handed her cabinet position, she wanted, more than anything, to address problems surrounding victims of domestic abuse and sexual assault.

And change is coming, Whalen promises. Now that the Liberals have won a second mandate, plans for a court designed to handle domestic assault cases—modelled after a successful version in Cape Breton—should be up and

As for Harris’ re-hiring, Whalen only says, that “you can’t vilify people for life. That makes sense to me.”

Coffin says she isn’t against rehabilitation or even second chances. In fact, when she learned that Harris had been re-hired, she reached out to the premier’s then-chief of staff, Kirby McVicar.

“I had a lot of guilt about how my actions would impact him as a parent,” Coffin explains. So she “proactively” emailed McVicar to say she was relieved that Harris’ employment meant a return to stability for his family.

What she didn’t expect was the government to be “arrogant” enough to put Harris back in his old job, serving as a public face of the party with his name attached to campaign press releases.

In an emailed statement to The Coast, Harris says his actions three years ago were “disgraceful.” While he’s “surprised and dismayed” that Coffin is now making public the details of her story, he insists that he’s changed since that night.

“Throughout this process, I have grown in my understanding of the incident, myself, my mental health and the types of relationships that make up my life,” Harris writes.

“I’ve now lost my job twice over this. I accept those consequences and I continue to seek ways to make amends for what I have done.”

The attack is something Harris says he deeply regrets, and will always be sorry about.

“I have

“I am deeply sorry for the profound negative impact my actions had on Michelle and her life.”

Three days after the assault, Coffin called the Victims’ Services number listed on the business card provided by responding officers. Her chief concern was fear that her name would get out to the public.

“Why?” she says the person on the other end of the line told her. “Papers don’t report on domestics.”

Her partner worked for the premier, she explained. The papers would report on that.

“Oh my god!” the Victims’ Services representative told her. “You have to tell the premier!”

The unsolicited advice was one of the many

“I didn’t have a lawyer. When you’re a victim, you don’t have your own lawyer,” Coffin says.

Three different Crown attorneys handled the case at court, which is a common occurrence. Cases are assigned to courtrooms, not lawyers. While one Crown attorney will prosecute the trial itself, multiple attorneys are often used for administrative appearances like arraignments, plea bargains and bail hearings.

But the process left Coffin feeling like she had no one to contact when she had questions. She says the PPS redirected her to police, who in turn had no information about the court case. There was no one in her corner.

“If they could have, they would have folded me up, put me in an evidence bag and taken me out when it was convenient.”

In the end, Coffin learned of Harris’ sentence just like every other Nova Scotian—by watching the news.

The hardest part was watching others describe what happened. The Liberals, the courts, the media: everyone had a version of events that wasn’t hers.

“Everyone has had a chance to tell this story—about me—but me,” she says. “And now I’m reclaiming it.”

The decision to go public wasn’t taken lightly. “I’m terrified,” Coffin says. “It’s only been in the last few months I’ve even told close friends what happened.... Some people will be hearing about this for the first time.”

That’s often the scenario when women report situations of violence, says Becky Kent. She sees it every day in her work with Transition House.

“People don’t realize they’re immediately thrust into judgement that they somehow caused this,” Kent says. “Quite often in that scenario, they become very isolated and they lose their voice.”

People discredit, invalidate and make excuses for the abuser, says Whynacht. We refuse to accept someone we know would hit their partner. The denial can lead people to actively protect the assailant, instead of the victim.

“We are often more concerned with defending the aggressor than we are with providing support and resources to victims of such violence,” Whynacht says.

Women who are victims of violence are often shut out of their own communities, adds Kent—be it friendships, family or from co-workers. The safe space that women used to cope with being in a violent relationship—even if it was done in secret—is suddenly taken away.

“They are

“To then face discrimination, judgement and criticism in your public life

Ironically, Coffin had company in that isolation from Harris. After all, they’d spent three complicated, painful years in each others’ lives.

“The only person in it with you is the person who punched and kicked you,” says Coffin.

They had a shared goal. Both of them wanted it all to be over.

“You align yourself with the person who can understand—in this case, my abuser.”

From her professional—and personal—experience, Coffin knows coming forward with her story puts her in a vulnerable position. There will be those who will accuse her of trying to attack the party she’s been loyal to for much of her career out of a desire for revenge. It’s not the case, she insists. Instead, this is a call for change.

“I’ve had a lot of time to reflect on my experience and put it in its place,” Coffin says. “I’ve also been able to step back from it and

She’s someone who knows how politics works, knows the players and knows the court system.

“I’m on the radio,” she says. “I teach it!”

And still, Michelle Coffin was utterly unprepared for what would follow after calling 911.

“I understand that I have some influence from my experiences and from my situation, professionally,” she says. “I can only imagine how someone who doesn’t have my background, or my education would feel.”

Above all, Coffin hopes coming forward now will help spark a desperately needed conversation both within and beyond Province House.

“There’s been a lot of talk about sexual violence...but there’s still so much stigma around domestic violence,” she says. “We need to start talking about this.”

It’s dark in the backyard now. The only light is coming from the neighbours’ windows and the streetlights beyond them. Coffin smiles.

“I think I’m gonna try to relax tonight,” she says. “I’ve earned it.”

The little dog’s barks are becoming more anxious and frequent.

“Don’t worry, Mo!” she calls up to the window. “It’s alright.”

———