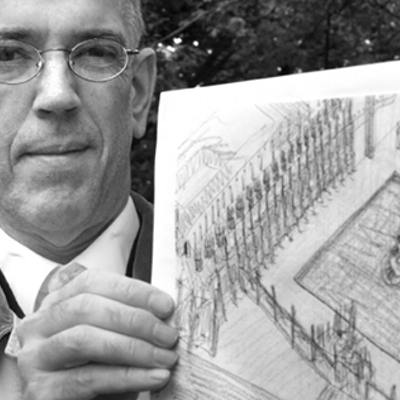

Hours before Jean-Pierre Gauthier's Machines at Play opens at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, the gallery is chaos. Yellow ladders loom among pushcarts of tools and cleaning equipment. Gauthier's work fills the air with honks, scratches of graphite, gurgling bubbles and piano flourishes.

It's a bit much for Gauthier, the 2004 Sobey Art Award winner. But the atmosphere suits the exhibition---a survey show of Gauthier's kinetic/found object/audio installations from 1997-2006, organized by the Musée d'art contemporain de Montreal.

Brooms, tools and a tool box, soap bottles and other janitorial themes dominate the show. It's a perfect metaphor for the Montreal-based artist. Although meant to keep things clean and orderly at their work, janitors' lives are seldom so neat and tidy. Gauthier strikes this same dichotomy in the restrained chaos of his work.

"I like to have systems that aren't linear. Life is something like that also," he says. "It refers to living and creating. My process is all about randomness and chance---the way things meet together."

In Gauthier's "Marqueurs d'incertitude," bug-like objects with graphite legs draw on the walls. Although the shape they create is determined by motors and other restraints, Gauthier can't anticipate the drawing: "I make them, see what it does and accept that as it is. It's like I'm making children."

Each piece in Machines at Play shares this principle. Creating technically and aesthetically refined pieces, Gauthier relishes his lack of control over the work. In "Chants de travail," Seussian instruments cycle through a random sequence of play. With his "Instants angulaires" series, networks of suspended plastic broom handles, filled with tiny granules, dance unpredictably. In "Le son de choses," sounds from quiet kinetic sculptures are randomly amplified in headphones. His motion-sensor piano, "Battements et papillions," is limited to a set amount of keys.

Gauthier, like the janitor, exists as a spectre in his work. Personal and biographical elements are obscured by the sound and motion of his environments. This continues for the viewer. You're invited to participate, but the pieces remain removed. Rather than illustrate life's visage, Gauthier depicts the random and busy soul. "The motion, the sound, all the dimensions and the references too---I try to bring them to another level."

Yet ghosts from Gauthier's past haunt his work. His life-sized, soap-scented janitor's room, "Le Cagibi," was inspired by friends who went through breakdowns. "It comes from a person that was very close to me [whom] I lost a couple years ago. It was his ghost. It started at that time. It's something that comes up very often," he says. "It's a loss, a grieving from that. And it goes to the sadness of the piano. It has this sorrowful quality."

Out of loss and change Gauthier harnesses permanence. The audio component is central to this, but often derided as noise. But as Gauthier points out, "noise is something you hear if you don't have a trained ear." He knows his sounds aren't traditional music, and he doesn't want his piano to play like a musician, because "that would be boring." He wants to teach the viewer to hear the sounds of universe. "The work has to be able to surprise me anytime. If it does that to me after three months of working on it in my studio, of course it's going to do that to someone the first time someone sees it. What I want [viewers] to experience is what I feel from the work."