Those questions came front and centre when architect Brian MacKay-Lyons went on CBC’s Information Morning to blast the city’s selection process for an architect for the library. He was followed on subsequent shows by Phil Townsend, HRM’s director of infrastructure and asset management, by Paul Frank of JDA Architects, a firm still in the running for the library contract, and by myself.

I have also independently interviewed MacKay-Lyons and Townsend, as well as other city staffers who were on the selection committee and otherwise involved in the process. I’ve also reviewed the documents (linked to, below) and looked at a number of buildings in Halifax built by various architecture firms under consideration.

How the city selects an architect

As per usual city procurement procedure, to find a architect for the library, the city sent out what is known as an expression of interest---basically, it’s asking “Who’s interested in getting this job? If you’re interested in getting the contract, show us that you have some expertise in this, and you’ll get considered.”

The actual expression of interest asks the interested firms to submit the following information

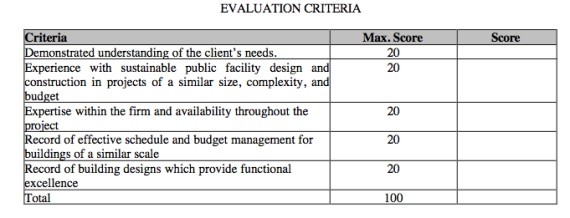

a) Experience of the firm as lead architect with buildings of similar scale, complexity and budget, emphasizing the firm’s record of meeting estimated budgetsAnd, according to the document (Page 9), “Individuals or Firms expressing interest in this project shall be evaluated based on the weighted criteria listed in Appendix A, Evaluation Criteria. Parties not scoring 80% or more on the listed criteria will not proceed to Phase II - Request for Detailed Proposal.” (emphasis added--I'll come back to it.) The criteria listed in the Appendix are as follows:

b) Identification and resumes of personnel to be directly involved in the project: principal, project architect, others expected to perform work including those of affiliated firms

c) Experience of the firm in public library construction

d) Experience of the proposed personnel with similar facilities

e) Demonstrated experience in sustainable architectural design

f) Approach to understanding of HRL and HRM’s needs

g) Description of the firms design and project management philosophy

h) Reference from recent similar projects, including full contact information, original budget, and final cost.

There are a couple of things worth pointing out in the expression of interest. First, under “project scope” (page 7) is the statement that “International design input would be considered an asset.” We’re not told why international input would be considered, but maybe that’s something architects would understand. Regardless, the including of international designers in the architectural team is not later considered a criterion for evaluation---so the statement just kind of hangs out there, raising questions that some bias may be at play.

In actual fact, of the 13 responses to the expression of interest, the six submissions that were “short-listed” for final consideration by the evaluation committee consisted of a local firm collaborating with an out-of-province firm, as follows:

Shore Tilbe Irwin (Toronto) with JDA (Halifax)Brian MacKay-Lyons, whose firm responded to the expression of interest but was not short-listed, says the focus on firms from out of area means that the library will be designed by people not familiar with Halifax and its culture, and the local partnering firm will have no significant input. (Listen to MacKay-Lyon’s interview with CBC here.)

Diamond- Schmitt (Toronto) with Lydon Lynch (Halifax)

Schmidt Hammer Lassen (Denmark) with Fowler, Bauld & Mitchell (Halifax)

HOK (St. Louis/Toronto) with Lydon Lynch (Halifax)

Moriyama Teschima (Toronto) with Barrie & Langille (Halifax)

KMPB (Toronto) with WHW (Halifax)

Paul Frank of JDA Architects, whose firm is still in the running for the library project, says that’s not the case. (Listen to Frank’s interview with CBC here.)

I have no idea how to evaluate those competing claims.

The second thing to note about the expression of interest is the statement that “Parties not scoring 80% or more on the listed criteria will not proceed.” But, in actual fact, the six architectural firms that were “short listed” included two teams (Diamond- Schmitt/ Lydon Lynch and KMPB/WHW) with scores of 72, and one (ShoreTilbe Irwin/JDA) with a score of 78. (See the full “pre-shortlist evaluation” here.)

The evaluation team whittled the shortlist of six down to four finalists, who may now proceed to the next stage in the selection process. But one of those four teams, ShoreTilbe Irwin/JDA, scored less than the 80 percent called for in the expression of interest.

"Among the evaluation team, there was a clear split between four and two," says Townsend, explaining the decision to reduce the "long shortlist" of six down to the "short shortlist" of four.

What of the seven firms that didn’t make any shortlist?

After some back and forth with city officials, the best answer I could get is that they weren’t rated at all. Rather, the selection committee looked at all the submissions and judged them as either worth evaluating or not. Those judged not worth evaluating---including MacKay-Lyon’s---were simply set aside.

I asked Townsend for paperwork on those decisions, but he said the paperwork, which consisted of the committee members’ “notes,” contained properitary information on the firms, and so could not be made public.

"It was a pass/fail criteria," says Townsend. "But based on in-depth discussion of the proposals---not a scored discussion, but a discussion where everyone looked at the overall quality of all the submissions."

I can find no description of the pass/fail process in any of the documents outlining the search for an architect for the library.

It’s easy, and sometimes unfair, to pick out a few contradictory or unclear statements in a complicated procurement procedure, but for a project of this size, and especially with regard to seemingly clear evaluation considerations, the process that the city went through for the library architect doesn’t seem as clean as it should have been.

MacKay-Lyons’ complaint

Without having access to the evaluation documents, MacKay-Lyons’ concerns did not raise much beyond the “there’s something fishy here” stage.

The procurement committee consisted of Judith Hare and Susan McLean, CEO and deputy CEE, respectively, of the Halifax Library; Andy Filmore, project manager for HRM By Design; and Terry Gallagher, an architect whose primary job for the city is as project manager for various construction projects.

MacKay-Lyons doesn’t fault the inclusion of library professionals on the committee, and he has respect for Filmore and Gallagher, but says they don’t have the expertise that is required for the project.

“The people making the decisions should be knowledgeable about the complete range of issues that are relevant,” he says. “So, most cities in Canada, if they’re going to do a building of this sort---like in Montreal, they just build a wonderful library. They had a jury that, for sure, included librarians, but was also peer-juried.

“The idea of peer jury proposal calls, or for competitions, is essential,” he continues. “We have professions because there is specialized knowledge. That doesn’t mean that the non-professionals don’t have a contribution to make, or an opinion that matters. In my opinion, a jury for a project of this significance for the city needs to be composed of the users, people who run the library, but also people who have deep interest in the city and in urban design and architecture. A proper peer jury situation has people of distinction, of stature that’s national at least in their field.”

Gallagher, says MacKay-Lyons, is “not a person who practices architecture and isn’t in the profession for the most part, and hasn’t the experience to be on that jury, if it’s about architecture.” And Filmore “has a master’s degree in urban design, and I would say has some qualification to be on the jury. [But] I’m not sure how much input he really had. The criteria for judging by the jury were not properly thought out either.”

Beyond concerns about the make-up of the committee, MacKay-Lyons, says the emphasis on paired teams---one local and one from out of the area---will result in a building that isn’t appropriate for Halifax.

“One thing that is absolutely clear is that no one who knows this city or understands its culture or even loves it, will be designing this building,” he says. “If the process continues, there will be a hand-off in some corporate office, in Toronto, likely, to a junior staff person who will design the building for our city of the century.”

Both in his interview with CBC and in conversation with me, MacKay-Lyons suggests that Judith Hare has a personal desire in seeing that HOK, is selected as the architect for the new library.

HOK was awarded the most recent two architectural contracts the library issued---for design of the Keshen Goodman Library in Clayton Park and for a “space study” for what would be required for the new central library. The space study might be relevant---for a building that has yet to move past the conceptual stage, the expression of interest has an interesting particular requirement for square footage: exactly 108,896 square feet. Make of that what you will.

MacKay-Lyons is quick to say he doesn’t want to be accused of “sour grapes” for not being selected. He certainly doesn’t need the money---his firm has plenty of work, including designing Canadian embassies. His intent in going public with his concerns, he says, is that he wants the best building for Halifax.

In defence of the city

City officials, obviously, have a different opinion.

Townsend defends the selection process in regards specifically to MacKay-Lyons.

“One thing we have to keep in mind through this process is there’s a difference between a respondent and the response,” says Townsend. “The evaluation team are charged with evaluating the responses---so everybody has the responsibility, when they submit their response [to the expression of interest], to spend the required time on it, to make sure they are selling themselves as best they can, because they’re being compared to other responses.”

One question considered by the committee, says Townsend, was “Did the response add any value to the expression of interest? It’s very easy, and in many cases it’s a pitfall, that firms regurgitate the information that you provided to them in the EOI. Well, we’re not stupid. We know this information, we already wrote it down. Don’t rejig it, and paraphrase it and send it back to us and think we’re going to think you’re brilliant. You have to add some value. We want to see what is your insight into this. We’re not looking for a design; we’re just looking for that spark that says, here’s a firm who’s really thought about this, they understand the context of it, they’ve taken the time to read and have chosen to add some value in their response. Those were the kind of criteria the team was considering in that pass/fail citeria.”

Although Townsend doesn’t say it outright, he implies that MacKay-Lyons simply submitted a crappy application.

Since I don’t have the responses to the expression of interest, and the paperwork the committee produced isn’t public, there’s no way for me to evaluate the issue.

As I see it, the city’s procurement process reflects a reaction to the ill-fated Point Pleasant Park design competition. You’ll recall that, after the destruction wrought by Hurricane Juan, there was private money made available for a competition to redesign the park. Many international firms produced designs, all of which fell flat with the public---the designs called for pulling out entire sections of the forest and building all sorts of structures and pouring concrete. The public reaction was so negative, and so vocal, that the entire process was ditched, and another---essentially the same process we’re now using for the library design---was put in its place.

“We’re very, very concerned about the public consultation piece of [the library design]---and this is not lip service,” says Townsend. “We understand how important this building is to the community. We can’t expect that four teams are going to be able to go out, do in-depth public consultation, effective public consultation, and come back with designs that are reflective of that. (Listen to Townsend’s interview with CBC here.) "We don't want to parachute something in here," he continues, explaining why a design competition wouldn't work. "It's a backwards way of getting public opinion---show them four designs and say, 'which one do you like?' instead of saying, 'let's have some conversations so we can develop a design that you do like.'"

Whatever problems might exist in the implementation of the city’s procurement process, it does give the city plenty of opportunity to drive it the direction desired by city staff, such that it’s unlikely that there will again be a public outcry to the degree of the Point Pleasant Park.

Certainly in the case of the park, the result is a pretty decent, understated plan that has wide acceptance by the public.

What is a good design?

But a park left mostly in its natural state is a very different thing than a public building in the middle of the city. Somewhere along the line, seemingly everyone who talks about the library has decided that it will be “an iconic building,” whatever that means.

The problem is that opinions about what’s a good library design differ---every person has a different opinion Architects might like one thing, the public generally might like something else. And opinions change over time. The city might like a building when it’s proposed, but hate the actual structure.

The most famous example of changing tastes is probably the Eiffel Tower, which was universally condemned as a monstrosity when it was constructed, but is now seen as a beautiful, elegant structure.

How do we work our way through all these issues for a library building? You can hand the whole thing over to professional architects and get something the public hates. Or, you can give the project to a subcommittee of city staffers and get a building that is so bland and nondescript that it doesn’t offend any sensibilities. Brian MacKay-Lyons says that the city’s system is flawed and should be interrupted, lest it result in the latter. Townsend says the city will come up with something interesting and important.

I’ll leave the question for another day, except to note that we, the public, do have some information, in the form of local buildings that have been designed by the various architectural firms under consideration. They are:

HOK/Lydon LynchWe will each have different opinions about these structures---personally, I abhor Purdy’s Wharf and the Metro Centre, but like the Seaport Farmers’ Market and NSCC, but plenty of others will no doubt have an opposing view.

Seaport Farmers’ Market (not yet constructed)

Waterside Centre (not yet constructed)

Keshen Goodman LibrarySchmidt Hammer Lassen /Fowler, Bauld & Mitchell

Citadel High

Metro Centre

Rebecca CohnMoriyama Teschima / Barrie & Langille

NSCC in DartmouthShore Tilbe Irwin/JDA

Purdy’s Wharf

Ken Rowe School of Management at DalBrian MacKay-Lyons

Computer science building at Dal

What’s needed at this point, seems to me, is a much larger public conversation about the library, and if nothing else, MacKay-Lyons has certainly generated that.