JT Davis had reached his breaking point.

The then-20-year-old New Glasgow resident called his girlfriend. They'd had an intense discussion about transsexuality earlier that day, and the focus of the conversation had stayed with him.

When she picked up the phone, he said, "You know that thing you were talking about? I think I'm it."

"I know," she said.

That was how, six months into their relationship, they acknowledged Davis's identity as a female-to-male transsexual.

Davis, now 26, considered transitioning—the process of counselling, hormones and surgery that allows someone to live completely as a member of they sex they feel they are.

In 2005, he moved with his partner to Vancouver. The trans population was larger out there, and he thought he'd have an easier time going through with transition in a city where no one knew him.

He adopted a "skater" look, dressing in baggy pants and hoodies and binding his breasts flat. Right away, people perceived him as male. "A 12- or 13-year-old boy, but still male," he says. At a skateboarding event, security even patted him down for weapons and didn't notice anything strange about his physique.

"I tried to be really masculine, to be legitimate," he says.

But instead of starting therapy to get his "T letter"—after a certain amount of time in counselling, usually three months, therapists will write a letter recommending testosterone therapy for healthy candidates—Davis got depressed.

Loneliness and isolation, he now knows, brought on the depression. His support system was thousands of miles away in Nova Scotia. But he blamed everything on being trans.

He talked himself out of transitioning and held onto his identity as a lesbian. I don't really need to do it. I can live as a butch and be happy. In 2006, he came back to Nova Scotia the same way he left: still physically female, still mentally male.

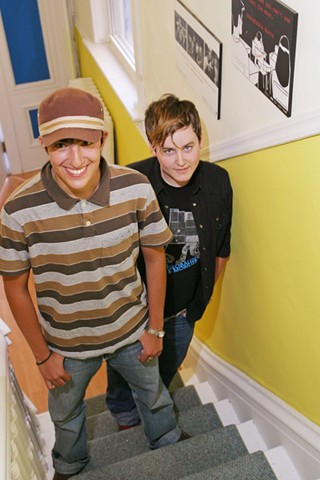

As support services co-ordinator at The Youth Project in Halifax, Davis shares his how-not-to-transition story with the trans youth who come to him for help.

"I've seen'em coming out at a younger age. The language is there. More supports are there," he says. "They're feeling a lot more comfortable to explore gender."

Twenty years ago, gays and lesbians crusaded for basic human rights—the chance to work without worrying about getting fired for being gay, not getting evicted when the landlord finds out a "roommate" is really a partner. In 2007, transsexuals are pushing for the same consideration.

Thanks to the age of connectivity, transgendered youth have a head start on their forebears. In the 1970s and '80s, most gay teenagers wandered the hallways of their high schools despondent in the belief they were the only ones there who were "that way."

Now, trans teens hop on the internet and hook up with each other on blogs, mailing lists and IM chat rooms. They know they're not alone, even if they are the only transsexual at their school.

They can turn on CNN or Oprah to watch video clips about trans kids and teens who, with their parents' and schools' support, live as members of their desired sex. Some medical practitioners even allow teenagers to take estrogen blockers and start surgical reassignment. That would have been unthinkable in 1987.

Davis says The Youth Project has also changed with the times, to reflect both the growing numbers of trans youth who need support and the acceptance that young people do indeed know their own identity.

For instance, The Youth Project used to be called the Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Youth Project, but it dropped the first three adjectives to include all identities along what's called "the rainbow spectrum." Signs posted throughout the centre ask visitors their name and pronoun preferences.

"Particularly in the past year, there have been so many more people coming in, asking for trans resources," Davis says, and not just the young people themselves, but their parents and teachers.

Medical figures put the ratio of female-to-male-identified people at one in every 100,000 biological females. That's far below the one in every 30,000 biological males given for the male-to-female population. Still, Davis says most of the youth who come to the project are female-to-male, or FTM.

The Youth Project has put on professional development workshops for teachers, health care workers and others who come in contact with trans youth. The sessions have attracted about 150 people. This month he's fielded calls from northern Cape Breton.

He's had teachers tell him about the trans kids they've had in their elementary school classes. It's clear: more authority figures recognize trans youth, and rather than sending them to the school psychologist for help in getting through their "phase," they want to give those kids support that says, "You're OK just the way you are."

The Youth Project just received $8,000 in funding to put more resources in place for trans teens and their supporters. Davis plans to use some of that money to publish an anthology of essays written by trans members who come to The Youth Project.

Yet, for all that, "they're still an invisible community."

Many of the youth he knows haven't begun a physical transition. Without parental support, permanent changes have to go on hold until they reach 19, the legal age of adulthood.

"They talk about it a lot," he says of the transitioning process. "I think there's a few that clearly want to."

But for some trans youth, transition is impossible. They don't want to lose their families, or they can't afford testosterone and surgery.

"That's a reality for a lot of people."

"I have a really deep-seated fear of losing the people that mean the most to me," Davis's friend, L. Gayoso, says.

Gayoso, a facilitator at The Youth Project and an employee of Venus Envy, comes from a South American, Catholic family. "Part of my fear of coming out to my family... is that they'll see as some kind of mental illness. I also worry that my family will automatically assume that, since I'm trans, I must be depressed. And that's just not the case for me."

Other young trans people simply don't want to transition, and Davis says their identities should be respected.

"Being trans is a lot of things. There are many ways of being trans."

Gayoso agrees.

"To be trans doesn't mean you have to transition with hormones and surgery."

Without the usual signs of masculinity, FTMs often struggle to be seen as men. Davis feels the pain every day.

After his return from Vancouver, he entered the professional world, where hoodies and baggy jeans didn't fly. The minute he began dressing more formally, he "passed" as male less frequently, despite wearing men's clothes and a tight surgical binder of double-thick, Lycra-reinforced material that his partner has to help him put on and take off.

The binders cover Davis's entire trunk, sort of like a corset, but a hair less restrictive. Binding like this produces a flat, masculine chest, but it doesn't come without a cost.

The binders restrict breathing and make him sweat. He sprinkles his body with corn starch to ease the irritation of perspiring in such an uncomfortable garment. "I put on so much corn starch, I feel like a baked good," he says.

"It's hard. You need to have a sense of humour.... But not passing doesn't mean I'm not trans."

In the seven years since he came out, he's realized that being butch is not enough. He's decided to transition despite his fears.

"It came to the point where I was just like, I don't care anymore."

This month he starts therapy to get his letter. He already knows which surgeon he wants to perform his chest reconstruction surgery, the sculpting of a male-appearing chest.

Gayoso goes back and forth about transitioning. S/he wants to be sure s/he transitions—or doesn't transition—for the right reasons.

Many trans youth who haven't started their physical transition feel pressure to start testosterone and get chest reconstruction surgery, s/he says.

"There's a lot of pressure to fulfill those things in your own life so that your identity is validated." S/he calls it the "not trans enough" syndrome.

Transition comes with too many myths. Gayoso knows people who believed taking testosterone would put an end to all of their problems. "I'm going to go on T and I'm not going to have all these insecurities," is how s/he summed it up.

Davis sees that kind of thinking every day. "I feel like we need to do a self-esteem workshop for trans youth," he says.

In the end, transpeople make decisions to transition based on their own complex, unique circumstances. In 2000, Davis just wanted to have society see him as male.

Now his choice comes out of a more intimate desire.

"To be able to be with my partner and not feel nauseous about my body would be amazing," he says.

He recognizes the good fortune in his life that will allow him to start transitioning—a secure job, support from his partner and friends, and the personal benefits that come with working at The Youth Project. They go a long way toward calming his worries about the changes that are coming.

Gayoso is also reaching the point where s/he feels s/he has to make some sort of physical change.

"Going to the beach and being able to take my shirt off..." s/he says, voice trailing off. "I think I'm coming to the point in my life where my own ability to be comfortable in my life outweighs the fear."

Brendan Dunbar freelanced this article for The Coast.