The annual CMHC rental housing report just came out, and one of its key numbers, the vacancy rate, will proceed to be tossed around for the next year when folks are talking about the housing crisis. But what does it even mean? And where do we go from here?

First, the TLDR: The overall vacancy rate in Halifax Regional Municipality increased a little bit (because of fewer students and slowing immigration), but prices still increased (because of steady demand, no caps on rental increases (at the time of the research) and not enough new units added to the market).

Here are some of the basics on what we’re actually talking about and why this report isn’t much of a reason to celebrate if you’re a renter.

- The vacancy rate is one of many numbers used to gauge the overall “health” of a rental housing market. (Whether the health of the renters or the health of the landlord is more important depends on who you’re talking to.) Report writer and CMHC analyst Kelvin Ndoro tells The Coast there's no perfect vacancy rate, but that the long-term historical average in Halifax is 3.8 percent.

- The vacancy rate tells us how many rental units at one time are sitting empty in a certain market (AKA Halifax in the month of October 2020). In this case, the lower the rate is, the harder things are for renters. When the number is low, that is an indicator that demand is high and availability is low.

- In 2019, Halifax’s vacancy rate hit a record low of just one percent. You didn’t have to be a data scientist to know that the situation was tough for renters in 2019; all you had to do was be in need of a place to live. A low vacancy rate looks like apartments being snapped up in seconds after being posted on Kijiji, landlords hosting bidding wars for units, and you telling every person you’ve ever spoken to you’re on the hunt for a new place, because word-of-mouth becomes an essential bargaining tool for getting a decent place to live. (Let us not forget about how systems that prioritize things like “knowing the right person” perpetuate systemic racism).

- This year’s report says that for the Halifax Census Metropolitan Area (CMA), the overall vacancy rate increased to 1.9 percent. (Still a tough rate for renters.)

- The report says there are two factors that affected this small increase and both were due to COVID-19:

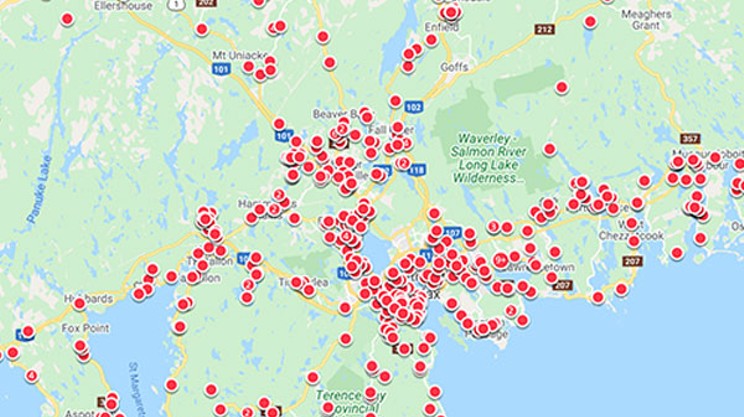

- The first is that online classes for university students in a huge university student town meant that apartments that were normally full of thousands of students each fall weren’t. The student theory checks out because the area that saw the highest vacancy rates was Peninsula South—which normally would be teeming with students vying for a decent apartment close to their school.

- The second is that thanks to COVID-19, immigration overall was down in Halifax (and across Canada), which over the past five years has been a big contributor to increased demand for rental housing. (This increase is twofold: 1. Halifax has seen record numbers of immigration in past years and 2. Newcomers are more likely to rent rather than buy a home.)

- More than just the vacancy rate, price is a huge part of testing the “health” of a rental market. Ndoro says price—and reducing the number of households that are paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent—is a more important focus than just moving the vacancy rate up and down.

- CMHC defines affordable housing for Canadians as housing that costs no more than one-third of their income. The 2020 data on how many of Halifax’s rental units are actually affordable for Halifax residents isn't available yet—but in The Coast’s 2019 rental housing survey 62 percent of the over 500 respondents said they weren’t earning enough money to see the city’s average rent hit their affordability threshold.

- Even with the vacancy rate increasing, the average price of a unit went up across the board. This throws a wrench in the commonly held economist stance on rental housing that increased demand increases prices, but decreasing demand will decrease prices. Ndoro says this is part of the delay in the market balancing itself out—a delay that just happens to regularly leave people in this city without a place to live.

- As per the report, the average bachelor apartment across all of HRM would run you $856 in October 2020. A one-bedroom on average was just over a grand, $1,016 (where do u live????), two-bedroom units jumped to $1,255 and over three-bedroom units increased to $1,455. On average, prices increased 4.6 percent. This might be fine if everyone in Halifax got a 4.6 percent raise last year. But considering how many people lost jobs this year—and those who kept theirs are now considered lucky, and lucky employees don't get raises—the chances are pretty slim. (Since 2016, the price of a one-bedroom has increased 20.2 percent. Minimum wage has only increased 13 percent since then. The proposed bump this April still lags behind what's needed to keep in line with rent increases.)

- 4.6 percent is also just the average increase, which is the result of some people’s rent being increased 20, 30 and 40 percent, combined with some people’s rent not being increased at all.

- The province’s protection for renters announcement didn’t come until November 2020, meaning the cap on rent increases at two percent won’t show up in any of this data—even though it was retroactively applied to September. Ndoro says next year it will. And here’s your reminder that as per the rules, no rental unit in HRM can have its price increased more than two percent a year until February 2022, or the end of the provincial state of emergency. (Not even if the unit changes owners. Tell your friends).

- There were more new units added to the market (something that’s necessary if HRM is going to catch up and then keep up with its increasing population) this year than last year, but not enough to balance the scale and keep price increases in tow. (This is in part because, often, the new unit added to the market is a higher-end unit, and comes in at a higher price regardless of market demand.)

- Interestingly, there were more empty units (a higher vacancy rate) in cheaper and older units, even though the market is still really tight. This “likely speaks to their inferior quality and need of renovations or redevelopment,” says the report. A nice reminder that yes, even renters have standards.

- And remember that CMHC’s data only surveys rental units that are in buildings with three or more units. So that two-unit house you live in on Hunter Street—which is a significant part of the housing stock–isn’t included. Regional council has pledged to build its own database of rental housing units in hopes of doing better than having “no idea” how many rental units there are in HRM, but that won’t be ready for a while and will require cooperation from landlords to offer up their info.

That's a lot of info, and enough for now. The Coast will keep coming back to this report and the layers of information tucked away in it over the next few weeks as we aim to help renters understand how the situation they’re in got so bad, and makes its humble plea to the decision-makers in this province (the large majority of whom are not renters) to take some extra moments to think about the humans who live in this city that find themselves first, locked into a rent they cannot afford and then, without a home at all.

What can you do now? We’ll have more info on this later, too. But for now, you can join the province’s recently launched housing affordability commission portal and share your thoughts.