My heart is racing. I'm sitting across a conference table from P, a social worker, in the meeting room of the Elsipogtog child and family services centre. He pushes a thick file of papers towards me, held together with an alligator clip. I've asked for these pages, because I need to know more than what I've known about myself, growing up here.

"How many people ask for their files?" I say to P, who watches me read as I begin to flip through the pages.

"None," he says.

I undo the papers from the stack and lay them out in chronological order. Month by month, year by year; it's like laying out pieces of a puzzle, the full image of which should be a version of a young me.

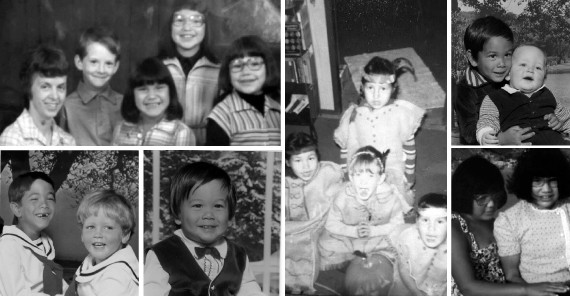

"The children were left alone, mother has been gone five days and has not returned," reads a report marked APPREHENDED, dated 1974. I would have been four years old.

These reports from the early years are confusing. I've blocked a lot of this out. I'm reading about my life for the first time. I thought I lived with my mom until I was seven. I find myself meeting my younger self through the pens of social workers. These papers say I've been a ward of the state—a foster child—since I was three.

"Mother was single mother with chronic alcoholism and no means to adequately care for children as she was frequently hospitalized due to drinking," reads an entry from 1975, signed by another social worker. "The house...is so deteriorated that it is not possible to return the children at the present time."

Flip.

"The children...have moved so often recently I expect they feel that this is the normal kind of thing. I told Mrs. M that I hope they will not have to move again unless it be to an adoption home as they have been moved too often," reads another recording from 1975.

Flip.

"Esther has been working very hard. Her marks are very good," reads my January 1979 report card, using my nickname. In 1981, when I was 11, I was sexually abused by a man from my community. My biological sister, who I was living with, was also being abused at the time. When kids in my community tried to talk to the adults about these things, it seemed like the first thing they'd say was: "Gepuniegsuwe!" or Would you stop lying! Between 1973 and 1981, I was placed in 10 different homes.

Flip.

"Esther tries hard but her skills need more work. I think we should seriously consider another year in Grade 5. Keep trying Esther," reads my 1982 report card. I remember not being able to listen to teachers. I would be thinking about the things that were happening to me at home and that there was no one to talk to. The school assigned me tutors. I didn't know how to tell them it wasn't the learning that was difficult.

Flip.

When I was 15, I lost my mom. I was with her that night. She was drinking and smoking cigarettes. My older brother was there, arguing with her. She wanted me to stay with her, but I was scared I'd get in trouble with my foster parents because I wasn't allowed to be around her when she was drinking.

The next day, I woke up and heard the fire alarm—at that time we had sirens at the fire station that you could hear clear across Elsipogtog. I didn't think anything of it, so I went back to bed. But then my foster sister ran down the stairs, woke me up and told me that my mom's house was on fire. I looked out the window and could see smoke coming out of the windows of her house.

Days later, during her wake, they let me go sift through the house. I could see her hand prints on the bedroom window, trying to break out. I felt alone, that things were never going to be the same again.

"Esther's plans to move back to her mother's have been shattered by her death. Work on this," reads a report from 1985.

Flip.

Although she struggled with her own past, and the sickness of alcohol, I always knew my mom loved all her 12 children. Behind the alcoholism there was a very beautiful, amazing, humble woman. She was still my mother, no matter what. Through these papers in my hand, I learn that social workers approached her more than once, asking her to put us younger kids up for adoption, telling her that there were off-reserve families ready to take us. She always refused.

Growing up I was mad and angry at the world. I didn't like that I was taken away from the love I could have gotten from my mom, if only someone had given her a chance and helped her out with her addiction. Instead, the immediate solution was to take us all away, split us up. I would see families with tight bonds, mothers and fathers and children laughing, and it would break my heart that I never had a chance to have that as a child growing up. Instead, I learned dysfunction, which translated into how I raised my own children. I thought this type of dysfunction was just the way of life.

I go home with this file, driving four hours from New Brunswick back to Halifax. Stopping in Sackville, at a diner, I start to weep at the table. When I get home, I crawl into bed, get under the covers with the pages and cry for the rest of the evening.

Flip.

Children all across Canada are taken from their families for all sorts of reasons. Comparing child apprehension on reserves to cases in the rest of the country, there are similar numbers of reports involving sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse or exposure to domestic violence. It is only in the area of neglect, due to "poverty, poor housing and caregiver substance misuse," that Aboriginal children are overly represented.

Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nation Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, notes that it is the glaring gap in funding between on-reserve child welfare—looked after by the federal government—and provincial child welfare, which looks after everyone else, that accounts for disparate apprehension rates of First Nations children. According to Blackstock, there are more First Nations children in foster care and permanent care than there were at the height of the residential school travesty. Prevention and family rehabilitation work cost money, money the reserves are not allocated by the federal government. And yet they are expected to provide child welfare services on par with the provinces in which they operate.

"One universal truth across all cultures is that the best place for children to grow up is in their families," says Blackstock, speaking at an event in early February in Halifax. "First Nations children, with the inception of Canada and even before, have always received less services on-reserve, but are judged as if they received more."

In 2007, Blackstock and the Assembly of First Nations presented a complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Commission based on this massive gap in funding. A tribunal was convened. Under the Canadian Human Rights Act, the tribunal has the legal authority to make a determination of discrimination, and order remedies. Seven years on, after the federal government spent over three million dollars to have the case dismissed on technical grounds, final arguments have been heard and a tribunal decision is expected this April.

In September 2014, I drive from Halifax to Ottawa. There's a gathering there of about 70 Aboriginal adoptees from across Canada. As children, mostly as newborns, between the 1960s and '90s, they were among the tens of thousands of Aboriginal kids who were placed in non-Aboriginal—mostly white—homes across the country, and the world.

In 1983, Patrick Johnson used the term Sixties Scoop to describe this particular phenomenon, in his publication Native Children and the Child Welfare System. The Department of Indian Affairs' statistics acknowledge that over 10,000 children were scooped during this time, but the number is possibly tens of thousands of children higher. The department's statistics refer to "Indian status" children only, while status itself may or may not have ever been recorded by social workers.

At the gathering in Ottawa, the coordinators tell us that people will be sharing their stories, which may be intense and emotional. They let us know that if we can't handle what is being spoken about, that there is a sacred fire outside where we can pray, and that there are elders who will be available to smudge us.

We break into four groups, and sit in circles. Each person gets a chance to talk about their upbringing, what happened to them and what they went through. Some people have the strength to share their stories. Others, when it comes to their turn, can only say their name. They gasp for air. In their faces, I can see that they don't know where to start. They've never talked about these stories to anybody, and this is the day they've been waiting for, to take this off their chest. These are adults, in their 40s and 50s, stolen from their culture, language and families. They start to speak, but the words don't come out.

I meet Colleen Cardinal, one of the coordinators for the gathering. Originally, Colleen is from Saddle Lake Cree Nation, in Alberta. Through research and investigation, Colleen managed to trace her own story. As an infant, she was removed from a hospital in Edmonton. At the same time, her two older sisters were taken from her parents' home. She and her sisters moved from foster home to foster home, until finding permanent adoption in a non-Indigenous household in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, over 2,000 miles away.

"That home that we were placed in had two non-Indigenous parents and they had their own biological son, and he was two years older than me," says Colleen. "Both my sisters and I were placed into this home and that home was really pretty violent for us, lots of physical and sexual violence was experienced there.

"It was really a household where we were put to work. We did all the work for the house, all the household chores, the family laundry, any kind of physical labour that needed to be done, my sisters and I did it all. And our brother, their son, didn't really have to do anything. When it came to physical punishment and sexual abuse, he was left untouched. He never had to worry about being molested or being hit. It was my sisters and I that had to always constantly worry about this. When we would come home from school we would dread what would happen next."

In our interview, which you can hear more of accompanying this story online at thecoast.ca, Colleen talks about the abuse, and running away from home, hitchhiking to places at a young age. She wasn't safe where she was, but in running away from the abuse, the act of running itself isn't safe. You're going to wind up meeting the wrong people.

"We all ended up running away from home by the time we were 15 years old because we just wanted to get away from there," says Colleen. "I remember at one time my sisters and I caught a bus to town, like a school bus, and we went to the children's aid society in Sault Ste. Marie and said: 'You know, our dad beats us, and we're scared of him and we're scared to go home.'

"They brought us right back home and they didn't listen to us. It's a horrible feeling as a child to not have other adults listen to you or take you seriously and put you right back in that really scary situation, so we just learned not to talk about it, and we just ran away. That was my experience in that home, and the effects that we experienced were long-lasting into our adult lives. That violence carried on into our lives and, you know, you're 15 years old out there in the world trying to survive and you're having all these things coming at you, like racism."

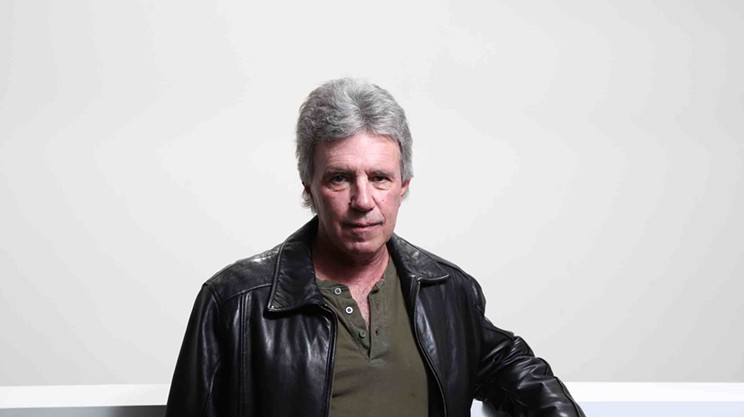

Andrew MacDonald was also adopted away at birth to a non-native family. The family was under the understanding that they would be receiving a "Caucasian" baby. When he was not "white," they thought there was something wrong with him.

"I was adopted under the pretense originally that I was going to be a white child," says Andrew. "I guess the social worker, after they had me for about a year, contacted my family and told them I was a native adoptee. I guess my parents had brought me to the doctor before that and they thought I had jaundice, which is a liver condition where your skin turns yellowish and you get darker. The doctor told them that he thought I was native as well."

Andrew was adopted as an infant from Bathurst, New Brunswick. Once, in passing, a social worker mentioned to him that he was Mi'kmaq/Maliseet, but his birth certificate still says Caucasian. He wants to find his roots, but the Department of Social Development in New Brunswick won't give him any information on who his biological parents are, or where he's from. They tell him that his biological mother signed a disclosure veto, which, under the provincial Family Services Act, means that his records are sealed from him.

Now, at age 39, he shows me a letter from the department, telling him to try for his records again in five years. By that time his biological mom might be dead, the letter says, and he would be able to ask the next family contact in line for permission to access his file.

Andrew talks about not fitting in. He has these non-native roots, which aren't really his. They're the adopted family's roots. And at the same time, he's trying to find his own roots. Sometimes what he sees, though, in singing with drum groups, or doing ceremonies, isn't what he wants to find.

"Most Indians grow up on a reserve, and they fight to get out of it," says Andrew. "With me it's kind of the opposite. With me I grew up off the reserve in an Inuit community in the north and I came south for university. It changed my life. And I've been fighting to get back into the reserve ever since. And as a result there has been a lot of turmoil in my life and a lot of negative things, because our people aren't the healthiest people in the world.

"It's been a trying experience, that's for sure. It's not one that is going to be over overnight. And there's a lot of work we have to do, and it's our own responsibility to work on ourselves, to try to make the best of what we've got."

Towards the end of the gathering in Ottawa, it feels sad. In the beginning, there was a distance between all of us. Then, as the days went by, the laughter started. We've just formed this bond, sharing these very personal stories, sitting together strategizing and learning how to cope with this.

Slowly, I'm watching the adoptees learn pieces of their culture. The doors are slowly opening for them. And then just like that, its time to go.

The plan is to reunite Sixties Scoop adoptees every year. As we wrap up, we have a giveaway of items we've specially brought to share. I give Colleen Cardinal an eagle feather. The feather represents who we are, from the tip to the end. It's almost like a lifeline that tells our story. Sometimes, in a feather, there are broken pieces, things that are not perfect. This usually represents how your life is going.

I speak to the adoptees in my language, Mi'kmaw. I start off by saying how honoured I am to be here, and that what I needed to share was that whatever they lost, that they can find it again and they were not alone. That they can learn their language. Learn their culture. And be proud of being Aboriginal people. That I would never forget each one of them and their stories.

The reason why I spoke in my language was so that it would help them see that speaking the language is so important—the foundation— and they can relearn it all.

There are two worlds out there and these adoptees are stuck in the middle. If I were to have gotten adopted out, I would have been like Andrew MacDonald or Colleen. I would have had the education. I might have had a better future. I would have become something. With that, maybe I could have gone back home and helped my community. But I have my culture. My language. Teachings. And the knowledge that I got from my elders. These just strengthen me more and give me more determination to keep fighting for hope, really, that life can turn around to a better path than what I've been through. Amugpana Gawasgatun Egmimajuawaganm. You've got to turn your life around.

Prime minister Stephen Harper has "apologized" to residential school survivors, and Sixties Scoop survivors currently have lawsuits against the federal government of Canada, at various stages in Ontario, British Columbia and Saskatchewan. These apologies seem false though, because funding to on-reserve child welfare is still far below the rest of the country, and children are still being scooped. The government has fought so hard against this even being acknowledged, and spent millions to ignore it. And at best, lawsuits only get some money for individuals.

The pain and suffering isn't just going away though. A lot of people have committed suicide, in my community, and in other native communities, over all the suffering, because they just can't handle the pain. Like Colleen and Andrew, and myself, there are some who have the strength to overcome it, but there's some who can't. Money isn't going to bring back identity, culture or language. And that's what this country has stolen and continues to steal.

Amugpana Gawasgatun Egmimajuawaganm. You've got to turn your life around.

Sixties Scoop

Listen to Annie Clair talk with Sixties Scoop survivors Colleen Cardinal and Andrew MacDonald