It was a dark and stormy night in Halifax, which meant the event hosted by Dalhousie's Roméo Dallaire Child Soldier Initiative was delayed, as its namesake founder was stuck on the tarmac at Stanfield airport.

On Monday, hundreds of Haligonians of all ages gathered at the Rebecca Cohn auditorium for Children’s Rights Upfront: Preventing the Recruitment and Use of Children in Violence.

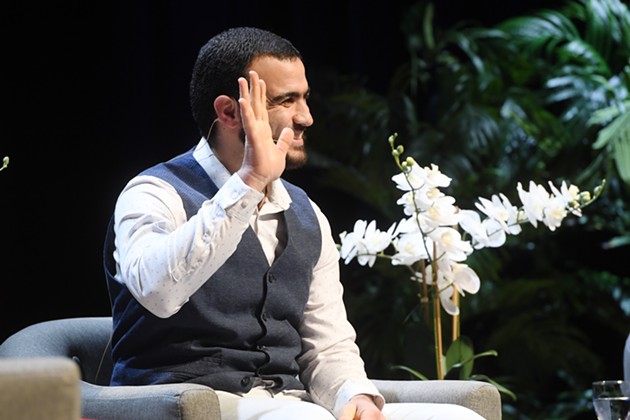

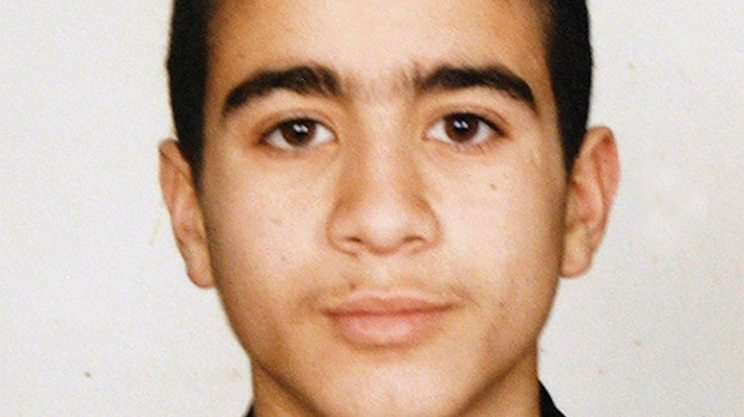

The event, a conversation between child soldiers Omar Khadr and Ishmael Beah, was lined up in advance of February 12 the International day against the use of child soldiers.

Security was tight, which meant there was a long wait to get inside from the rain— giving ample opportunity for the attendees to be heckled by a vocal veteran. The medals on his jacket indicated he’d been to Afghanistan, maybe more than once.

“I thought this was the city that named a ferry after Chris Stannix?” he shouted. It is—in 2014, after public voting the city named the Woodside ferry after the soldier killed in Afghanistan in 2007.

The interesting parts of the conversation at Dalhousie centred around the difference between Omar Khadr and Ishmael Beah, in how the two men are treated. As a child soldier coming out of Africa, it was easy for Beah to earn sympathy. Years of Sarah McLachlan-scored commercials conditioned Canadians to feel sympathy for child soldiers in his part of the world. Khadr's reception by Canadians has been decidedly different, a point which Beah himself made.

“If Omar Khadr was your child, would you feel differently?” asked Beah. “I don’t want your sympathy if it’s selective.”

One of the issues facing Khadr is that he was brainwashed as a child into fighting for al-Qaeda. The veteran outside the event believed that his colleagues have been abandoned by the federal government, with many of their ranks homeless, struggling to access benefits and ending their suffering by their own hand.

Khadr, goes the argument, is undeserving of the $10.5 million settlement he received for the violation of his rights as a citizen after 10 years of imprisonment in Guantanamo Bay. And the human-rights argument for giving him a payout doesn't wash with veterans who have lost friends to al-Qaeda or government neglect.

Of this resentment, Khadr said: “It’s hard to forgive when people think you hurt them directly," adding “My critics are human. They are in pain and need help.” When asked what he would say to the veteran outside, he said “I wouldn’t say anything...it’s a free country.”

Beah spoke of how recovering from his time at war took years. He says it’s unrealistic to think that a single conversation will change anyone’s point of view, but it starts the process. “I’m really proud of what happened tonight,” said Beah after the event. “Otherwise we’re just polarized. Everybody just clings to their version of the story and nobody can contest it.”

For the veteran in front of the Cohn, perhaps shouting into the wind was part of a healing process. Maybe it’s an expression of anger that of the two men, only one is seen to have been adequately compensated by the government for being a Canadian who suffered through war.