When Halifax resident Mary Thibeault died in her St. Petersburg, Florida, winter home, she left an estate valued at over half a million dollars and a will naming 13 people and five charities as beneficiaries. One of the beneficiaries was Halifax mayor Peter Kelly. Thibeault called Kelly a friend and valued his judgement: In addition to naming Kelly an heir, she chose him to be both executor and trustee of her will, responsible for distributing Thibeault's wealth to the other heirs.

Thibeault's estate is not especially complex. There are no property title disputes, and nobody has come forward to say that Thibeault owed them money before she died. Typically, such simple estates take about 18 months to work through probate---the legal process of distributing an estate---and they unfold in a straight-forward manner: the court recognizes the executor, the heirs are notified, an inventory of the estate at the deceased person's death is taken, property is sold off, money is distributed to heirs and a final accounting is submitted to the court.

But Mary Thibeault's estate has not moved successfully through probate. More than seven years have passed since Thibeault died on December 7, 2004, and there has been no full accounting of her estate. Some heirs have received some of their inheritance, but are expecting more. One heir has died waiting for his full inheritance, others are in ill health and one is very elderly, nearly 100 years old. Charities named as heirs have not been notified that they are to receive part of the estate, and have not received a dime.

Thibeault's will and the probate file related to her estate are public documents at Nova Scotia's Probate Court. But there is no indication in the file what is causing the delay. To find out, The Coast has interviewed dozens of people and examined hundreds of documents over an 11-month investigation. We have obtained Mary Thibeault's personal bank records, from both before and after her death, and have examined correspondence to and from Peter Kelly's lawyer.

That investigation reveals that one reason the Thibeault estate remains open is that, after she had died, Kelly transferred over $160,000 from Thibeault's personal bank account to himself. The transfer of that money has become a sticking point in negotiations to settle the estate, with some heirs insisting that $145,000 of it be returned to the estate, while Kelly says he will do so only if the heirs keep secret about it.

Tuesday evening, after the city council meeting, The Coast approached Kelly and told him we intended to go to press Wednesday with an article about the Thibeault estate that contains serious allegations against him, and we wanted to give him an opportunity to respond.

"That's in the hands of the lawyer," said Kelly. "You need to talk to the lawyer."

Wednesday morning, we called Kelly's lawyer, Harry Thompson, and told him Kelly had directed questions about the Thibeault estate to Thompson.

"First of all," said Thompson, "he's my client, and ethically I'm bound by solicitor-client privilege, and anything that is public you can find at the office of the registrar of probate in Halifax."

We then asked Thompson if he would answer further questions.

"No. No, I won't," said Thompson. "I know it frustrates your work, but nonetheless we jealously guard that relationship with every client."

A friendship develops

In 1945, Mary Thibeault and her husband, Joseph, bought the Prince's Lodge Motel on the Bedford Highway. The motel was a small building high on a bluff to the west of the highway, overlooking the Bedford Basin. The couple lived in one of the units until Joseph died in 1984, and some time later, Mary had an apartment/office space built closer to the road. She managed the motel, without employees, until she was into her 80s. She sold the motel in 1998 for $600,000, and soon after the property was developed into the apartment complex now known as Prince Edward Estates.

Mary Thibeault was friends with Peter Kelly's father, Mort, and the elder Kelly would often bring his son along when he visited the motel. As Peter became an adult, he too became a close friend and advisor to Thibeault.

The motel was a seasonal operation, and Thibeault wintered in Florida, buying a trailer in the Venetian Mobile Home Park in St. Petersburg. After she had sold the motel, Thibeault moved into a small apartment in King Andrew Tower, a seniors' complex on Main Street in Fairview, where she spent her summers.

Kelly was deeply involved in Thibeault's affairs. Dorothy Clarke, the owner of the Florida mobile home park, tells The Coast that Kelly travelled several times to Florida to help with upkeep of the trailer. In 1995, when he was mayor of Bedford, Kelly spoke on Thibeault's behalf at Halifax city council about a zoning issue regarding the motel property. And beginning some time before Thibeault's death, Kelly managed Thibeault's money and was in possession of her chequebook.

Thibeault wrote the final version of her will on October 30, 2003, and named "my friend, Peter Kelly" as both an heir and as "executor and trustee" of her estate. Kelly was to receive five percent of the estate and he was charged with disbursing the rest of the estate to the 17 other heirs---five charities and 12 people---who were each to receive either five or 10 percent of the estate according to Thibeault's instruction.

"It is my direction," Thibeault said in the will, "that my Executor shall be entitled to a minimal fee for services rendered with respect to my estate. It is my intention that the specific gift provided for in the Will to my Executor is in lieu of executors' fees aside from the the minimal amount stated herein."

While the will does not otherwise state what the "minimal amount" should be, it seems clear that Thibeault felt the five percent of the estate she granted Kelly was sufficient payment for his services as executor, and aside from minor expenses he may incur, he was not to charge the estate much, if anything, for his services.

The next year, 2004, Thibeault died in Florida of natural causes. Kelly was in communication with Floridian officials, was the source of information for Thibeault's death certificate and arranged for Thibeault's body to be transported back to Nova Scotia. He attended her funeral, and then the burial at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Sackville.

Mary Thibeault's money

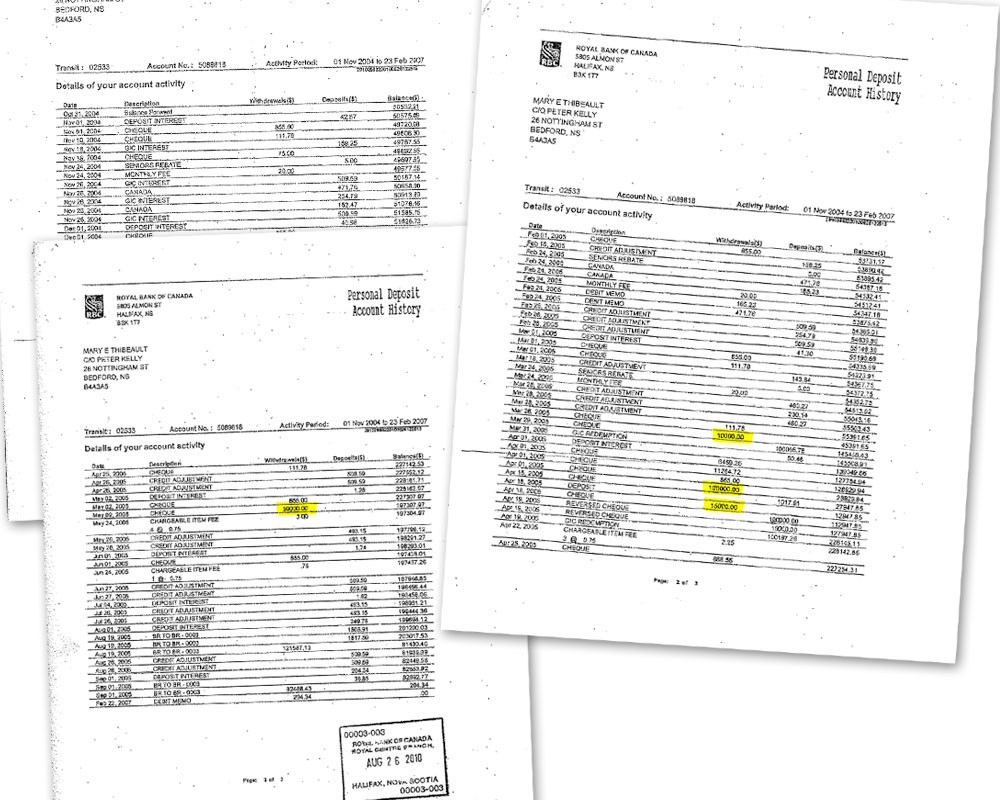

The Coast has examined Mary Thibeault's bank records. Until the the date of her death, December 7, 2004, the records show no unusual activity in her bank account, which was held by the Royal Bank of Canada branch on Almon Street.

The cheques presented at the bank after Thibeault's death, however, are interesting.

The five payments for her Fairview apartment for the months of January through May, 2005, were on sequentially numbered cheques signed by Thibeault but filled in, including the dates, by a distinctive handwriting---blockish letters that often lean slightly to the left, and "E"s written like backwards 3s. That handwriting looks like the handwriting that is on forms Peter Kelly signed and submitted to the probate court.

The apartment rent cheques were dated the first of each month and deposited by Templeton Place, the owner of the apartment building, a few days into each month. A similar pattern applies to a storage unit Thibeault had rented.

It cannot be determined from the bank records if Thibeault signed filled-in, post-dated cheques for the apartment and storage rental before leaving for Florida for the winter, or if she had signed blank, undated cheques before leaving.

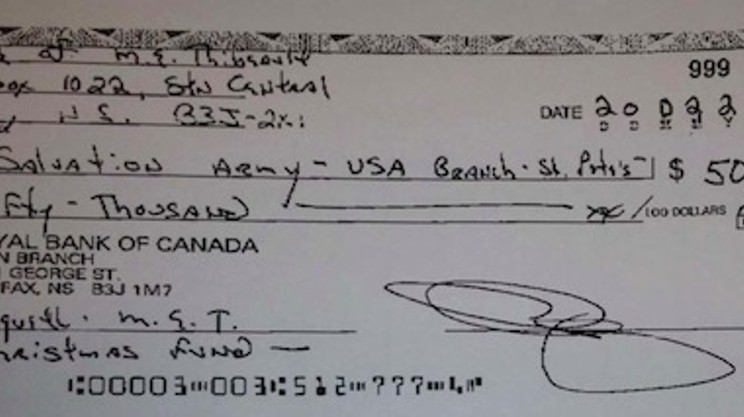

On March 24, 2005, the same day the probate court recognized him as executor of Thibeault's estate, Kelly wrote and signed a cheque to himself for $10,000 from Thibeault's personal bank account. The memo line on the cheque reads "expenses." There is no accounting for those expenses filed with the probate court.

Toward the end of March, 2005, there was roughly $45,000 in Thibeault's personal banking account. On the last day of that month, Peter Kelly redeemed a GIC in Thibeault's name worth $100,066.78 and deposited it in her bank account, bringing the balance of the account up to about $145,000.

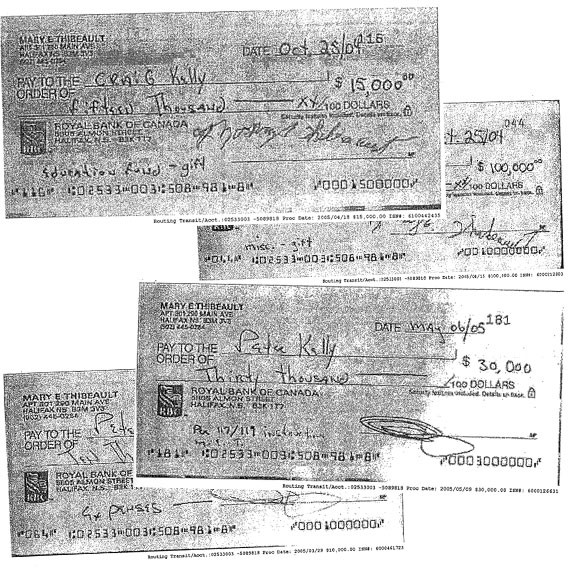

Then, on April 15, 2005, a cheque from Thibeault's account and made out to Peter Kelly for $100,000 was deposited in a bank account at the TD Bank branch on Barrington Street, across the street from City Hall. This cheque was signed by Mary Thibeault, but was filled in, including the date, with handwriting that looks like Peter Kelly's. The date on the cheque is October 25, 2004, more than a month before Thibeault died and almost six months before it was deposited in Peter Kelly's account at TD bank. Written on the memo line on that cheque is "misc.-gift."

Three days later, on April 18, a cheque for $15,000 to Kelly's son Craig Kelly was deposited in the Bank of Nova Scotia. This cheque was signed by Mary Thibeault but filled out by handwriting that looks like Peter Kelly's; it too was dated October 25, 2004. The memo line on that cheque reads "education fund-gift." At the time, Craig Kelly was 14 years old.

Thibeault's bank, however, reversed the $100,000 and $15,000 cheques, returning the money to Thibeault's account. There is no explanation in the records reviewed by The Coast explaining why the cheques were reversed, but the same day the bank reversed the cheques---April 19, 2005---Peter Kelly redeemed and deposited into Thibeault's account a second GIC, this one valued at $100,197.26.

The next month, on May 6, 2005, Peter Kelly wrote and signed a cheque to himself from Thibeault's account for $30,000. The memo line on the cheque reads "per 117/119 instructions M.E.T."

That cheque cleared.

Eight months missing

The point of the probate process is to provide a public, and transparent, accounting of the deceased person's property and how it was handled and dispersed by the executor. To that end, an inventory of the deceased's estate is to be filed promptly---within 90 days---and all handling of the property and money is documented in subsequent reporting. Heirs and other interested parties are therefore able to challenge various expenditures as inappropriate and, based on the public accounting they have access to, if the heirs are dissatisfied with the executor's actions, they can petition the court to remove the executor.

The probate court named Kelly executor of Thibeault's estate on March 24, 2005. By law, he was to file an inventory of the estate within 90 days---by June 24, 2005---but Kelly missed that deadline.

On June 30, 2005, deputy registrar of probate Pat Pozdnekoff notified Kelly that he was in violation of the Probate Act and had 30 days to comply.

Kelly failed to meet that deadline as well, and so on August 8, 2005, Pozdnekoff issued a court order requiring Kelly to file the inventory "upon receipt of this Order."

Bank records examined by The Coast show that 11 days later, on August 19, 2005, there was a branch-to-branch transfer of over $120,000 out of Thibeault's personal bank account. "Peter transferred $121,587.13 to another account presumably his own," wrote someone with knowledge of the transfer, in documents given to The Coast.

The person with knowledge of the transfer said that Kelly justified it as replacements for the reversed $100,000 cheque to Peter Kelly and the $15,000 cheque to Kelly's son Craig, plus unspecified expenses related to the estate.

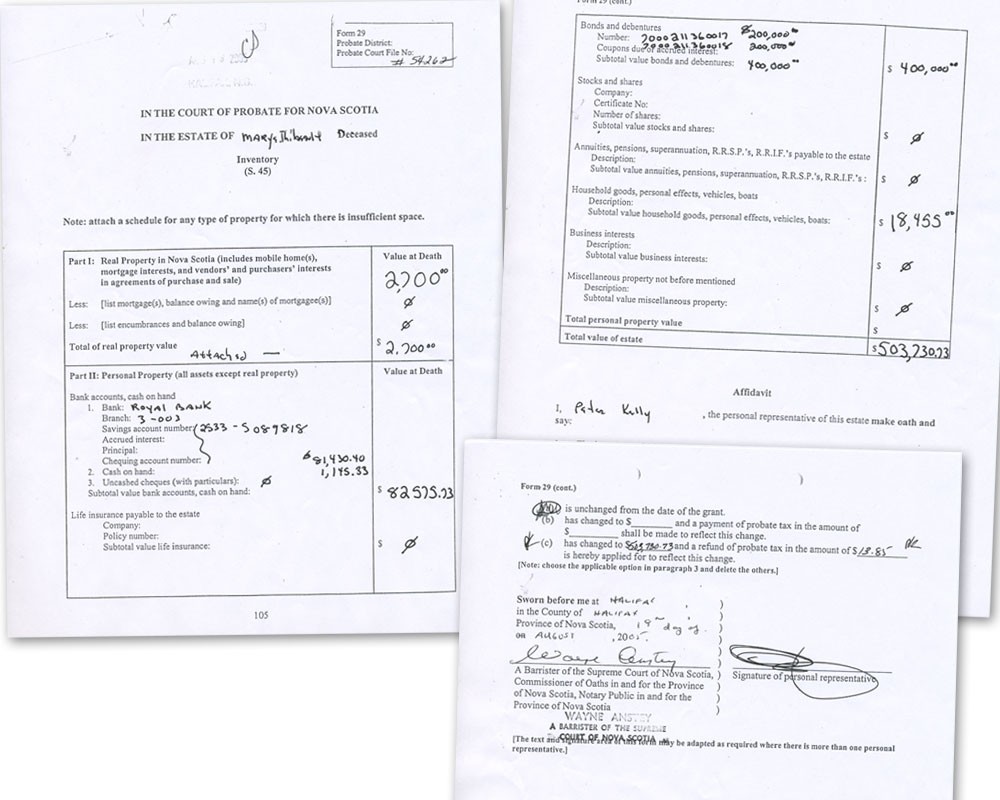

That same day, August 19, 2005, Kelly submitted an inventory of the Thibeault estate to the probate court, listing just $81,430.40 in Thibeault's personal bank account---the amount left after the $121.587.13 had been transferred.

The inventory also lists a small piece of property near Kearney Lake, two GICs totalling $400,000 and some cash on hand. Kelly claimed the total value of the estate was $503,730,73.

The inventory was sworn before Wayne Anstey, a lawyer who was then second in command in the city bureaucracy. (See the inventory on page 11.)

With the aim of achieving a complete accounting of the estate, instructions on the probate inventory form are very clear that the inventory is to represent the deceased's property's "value at death."

However, the inventory of Thibeault's property that Kelly swore an oath to and submitted as an official document to the court does not represent the value of her estate "at death"---on December 7, 2004---but rather the value of her estate more than eight months later---on August 19, 2005.

Over those months between Thibeault's death and the inventory of her property, there was considerable activity in Thibeault's personal banking account. Besides the rent and other minor payments, Kelly had redeemed and deposited the two GICs, each valued at slightly over $100,000.

Also, over $160,000 was moved from Thibeault's account to Kelly's control. (That is $161,587.13 exactly---the total of the March 24 cheque for $10,000, plus the May 6 cheque for $30,000 and the August 19 transfer of $121,587.13. That figure does not include the $100,000 or $15,000 cheques, which were reversed.)

None of the activity in Thibeault's personal banking account between her death and the inventory is reported in any documents submitted to the court. The Probate Act makes allowances for corrections---the executor can submit a supplemental inventory---but over six years has passed since Kelly submitted the inventory, and he has not corrected the record.

To this day, there is no public accounting of the money transferred from Mary Thibeault's personal bank account to Peter Kelly after her death. Because the activity in Thibeault's account was not reported to the court, the heirs were unaware that Kelly had removed over $160,000 from the account. It would take years before some of the heirs would become aware of the transfer, and as luck would have it this knowledge would come just before the bank records were scheduled to be destroyed.

Gift or not?

While Thibeault's will authorizes Kelly, as executor and trustee, to make investments and pay expenses, it did not authorize him to personally borrow money from the estate.

Of the $161,587.13 moved from Thibeault's bank account to Kelly's control, according to the memo line on a cheque and an explanation written by someone with knowledge of the branch-to-branch transfer, Kelly claims that $16.587.13 was for legitimate expenses related to the handling of the estate. The rest, $145,000, is a matter of contention.

As subsequently told to some of the heirs, Kelly claims the $145,000 reflects Thibeault's stated desire to convey the money to him and his son as a gift. The $30,000 cheque Kelly signed says "per 117/119 instructions M.E.T." The other $115,000---part of the transfer Kelly made out of the account---he claims replaces the reversed "misc.-gift" and "education fund-gift" cheques.

Does it make sense that Thibeault gave the cheques to Kelly as a gift?

The reversed $100,000 and $15,000 cheques---are dated October 25, 2004; at that time there was only about $50,000 in Thibeault's bank account. Was the understanding that Kelly would cash them after the maturation of her GICs? We've seen that for her apartment and storage unit rent, Thibeault either left post-dated filled-in cheques or undated blank, but signed, cheques. If she was in the habit of post-dating cheques, why would wouldn't she post-date the "gift" cheques to the date the GICs matured? On the other hand, if she was in the habit of leaving signed, but blank, cheques, Kelly could fill in whatever he wanted.

Additionally, the timing of the redemption of the GICs raises a question: With the small increase over $100,000---$66.78 for one, $197.26 for the other---were they fully mature?

Another issue is the "misc.-gift" written in the memo line of the $100,000 cheque. Who calls a $100,000 gift---about a sixth of the total value of Thibeault's estate---miscellaneous?

More to the point, Thibeault could have simply written the $145,000 gifts into her will, but she did not.

Also, Kelly would later agree to return the $145,000 to the estate---on the condition that the matter be kept secret. This insistence on confidentiality, coupled with the absence of an account of the transfer on the probate inventory, raises serious questions about Kelly's intent.

Heirs not notified

The Nova Scotia Probate Act outlines how heirs should be told of their coming inheritance: The executor should fill out a form---in the Thibeault case it is Form 24, "Notice to Beneficiaries (Residuary)"---and send it via registered mail or a process server to each of the heirs. The registered receipts showing that delivery was made then become part of the court record, and the executor fills out another form---Form 28, "Affidavit of Service-Notice of Grant"---in which the executor is to specify which heirs were notified, and which heirs the executor could not identify or find.

As executor of the Thibeault estate, Kelly has failed to file both Form 24 and Form 28. The requirement is that after being named executor, the executor must notify all heirs within 30 days. Nearly seven years have passed since Kelly was named executor and there's no indication in the court records that he has properly notified any of the heirs.

Of the 12 people besides Kelly named in Thibeault's will, nine were told by word of mouth that they are heirs. These nine people are either related to Thibeault or they are close family friends living in the Halifax area.

The tenth and eleventh people named in the will are Thibeault's brother, Fabian Halleran, and a second cousin by marriage, Yvonne Comeau. Both died before Thibeault.

The twelfth person named in the will is "my friend, Ann Levey of Baltimore, USA." As a child, Thibeault spent many summers in Baltimore, where she struck up a friendship with Levey; the pair remained close, if distant, friends for the rest of Thibeault's life.

Levey was presumably alive when Thibeault wrote her will in 2003. The Coast has not been able to locate her or her heirs.

"In the event that an heir is missing, there are procedures in place to protect missing or unascertained heirs," explains Cora Jacquemin, the current registrar of the Nova Scotia probate court. "The personal representative is expected to make every reasonable effort to find a beneficiary who is missing. ie: contact former friends and family, searching canada411.ca; placing an ad in the major newspaper of the last known city where they resided, to name a few methods."

Mary Thibeault’s heirs

To receive five percent of the estate:

- Patricia Richardson (sister)

- Fabian Halleran (brother, pre-deceased Thibeault)

- Sharon Mahoney (niece, Fabian Halleran’s daughter)

- Peter Halleran (nephew, son of Fabian Halleran)

- Elisabeth Herritt (cousin once removed)

- Greg Oldfield (second cousin)

- Yvonne Comeau (husband’s cousin, pre-deceased Thibeault)

- Edward Brunt (friend, died in October 2011)

- Phyllis Brunt (friend, widow of Edward Brunt)

- Catherine Ivany (friend, wife of Raymond Ivany)

- Raymond Ivany (friend, husband of Catherine Ivany)

- Ann Levey (friend, not yet located)

- Peter Kelly (friend)

- Canadian Heart Foundation

- Canadian Cancer Society

- Canadian Diabetic Society

To receive 10 percent of the estate:

- Salvation Army, USA branch

- Canadian National Institute for the Blind (Nova Scotia)

If Kelly made any such attempt to locate Ann Levey, he has not reported it to the court. Nor has he identified Levey on Form 28 as a un-locatable heir.

Thibeault named the charities in her will as the Canadian Heart Foundation, the Canadian Cancer Society, the Canadian Diabetic Society, Salvation Army USA branch and the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (Nova Scotia). There is no indication in the court record that any of the charities have been formally notified they were named in Thibeault's will, as required by the Probate Act.

The Coast contacted the fundraising or estate-giving managers of two of the charities, and both were completely unaware that they are to receive tens of thousands of dollars. The charities' managers declined to be quoted for this article, but one said the charity would contact court officials for clarification of the organization's rights.

Cora Jacquemin, the registrar of probate, says "charities are also to be served under the same time lines as an individual---30 days."

But in fact, after being named executor, and then being ordered by the court to file an accounting of the estate, Kelly took no further action on the estate. No heirs were notified as prescribed by law, and none of the other heirs, besides Kelly himself, received any money from the estate.

Nearly four more years of inactivity would pass. Then, Mary Thibeault's sister, Patricia Richardson, who was also an heir and then in her 90s, wrote in frustration to the court. "My sister Mary Ellen Thibeault died December, 2004," wrote Richardson on September 10, 2009. "To date her estate hasn't been settled. I would appreciate any information regarding this matter."

The court then wrote a terse letter to Kelly notifying him that he was in violation of the Probate Act. Kelly responded in three ways.

First, Kelly paid $25,000 to each of nine family members and Halifax-area friends who were aware they were named in the will. Four years before, having been ordered by the court to give an accounting of the estate, Kelly placed its value at just over half a million dollars; $25,000 represents about five percent of that value. Kelly also paid himself $25,000 (beyond the disputed $145,000) with five cheques for $5,000 each.

Second, Kelly retained Halifax lawyer Harry Thompson to look after the estate. Through the years, Thompson has worked on numerous other probate cases; an examination of several of those case files shows that Thompson routinely files the Form 24 notification to heirs, the registered mail receipts and the Form 28 Affidavit listing which heirs were notified and which heirs could not be located. He clearly knows the law, and would presumably advise his client, Kelly, of his responsibilities. But Kelly has still not formally notified the charities.

Third, Kelly wrote a letter to Patricia Richardson, Mary Thibeault's sister.

"As you are aware," he told Richardson, "you have received your allocation of the estate both here and in the States other than your appropriate share of those that predeceased as per Mary's instructions. The lawyer that I've retained has instructed me to get particular information pertaining those individuals, as well as additional information for tax settling. Once that information is at hand, I will certainly forward to you and all others you[r] residual allocations."

The letter refers to the terms of Thibeault's will, which called for each of the nine family and Halifax-area friends, as well as Kelly, Ann Levey, Yvonne Comeau, Fabian Halleran and three of the charities, to receive five percent of the estate; the two other charities were to receive 10 percent each. In the event that any of the heirs died before Thibeault, the will called for that heir's portion to be distributed pro rata among the other heirs.

Two heirs---Fabian Halleran and Yvonne Comeau---did die before Thibeault. Additionally, if Ann Levey died before Thibeault, or if she truly can't be located, her five percent would likewise be distributed among the other heirs.

If the August 19, 2005 inventory of the estate Kelly submitted to the court was correct, the 10 people, including Kelly, who have already received $25,000 should each get about $4,500 more. The three charities that were to receive five percent should get about $29,500 each and the two charities that were to get 10 percent should receive about $59,000 each.

But the inventory Kelly submitted to the court may not be correct. If the $145,000 Kelly removed from Thibeault's bank account is returned to the estate, then the heirs are due more money still. In that case, the nine people who have already received $25,000 should each get about $7,250 more. The three charities that were to receive five percent should get about $32,500 each and the two charities that were to get 10 percent should receive about $65,000 each.

But those are ballpark calculations and do not reflect a court-affirmed calculation of the true value of the estate, nor do those figures account for ever-increasing legal bills that may be paid from the estate.

One of the heirs, Edward Brunt of Halifax, has died while the estate remains unresolved, at least one other heir is in poor health and a third heir, Thibeault's sister Patricia Richardson, is nearly 100 years old.

Some heirs negotiate

In May of 2010, some of the Thibeault's heirs---her family and the Halifax-area friends---contacted Halifax lawyer Lloyd Robbins and asked him to look into the probate file. Robbins had been Thibeault's long-time lawyer, representing her on property matters and overseeing the writing and filing of her will. The nine family members and Halifax-area friends ended up hiring Robbins later that year.

If they feel the estate is being mishandled, beneficiaries to an estate have the right to petition the court to remove the executor, but the Thibeault heirs took a different approach: They had Robbins begin negotiations with Peter Kelly and Kelly's lawyer, Harry Thompson.

The timing of the hiring of Robbins was fortuitous. Banks are legally required to maintain past account information for six years. Had another year passed, records of the April 2005 cheques from Mary Thibeault's bank account to Peter Kelly and Craig Kelly, the May cheque for $30,000 to Peter Kelly and the August 2005 transfer of $121,587.13 out of the account may have been destroyed.

But because Robbins was retained when he was, the heirs were able to learn of those payments, and could question the removal of $145,000 from Thibeault's personal bank account. They thought that money should be part of the estate.

The heirs also had concerns about the disposition of Thibeault's trailer in Florida--- Kelly had said that the trailer had been sold for back taxes and so there were no proceeds from the sale. But if the trailer was lost to the estate because of indifference or incompetence on Kelly's part, it was arguably a loss of value to Thibeault's estate, and therefore ultimately to the heirs.

Contacted by The Coast, Venetian Mobile Home Park owner Dorothy Clarke says that after Thibeault died, Kelly never came back to the mobile home park, and did not return repeated phone calls and letters to address the situation. Clarke says she paid the licensing fee on the trailer for several years in order to stay in compliance with state law. Having paid the licensing fee, and having missed out on a few years of rent payments, Clarke finally went through the abandoned property process and sold the trailer to another park resident.

The trailer aside, the nine heirs who had retained Robbins wanted the $145,000 returned to the estate; Kelly removed as executor; someone else named executor and the estate properly resolved as it should have been many years before.

But Kelly took an aggressive counter-position. He would only return the $145,000 and step down as executor on the conditions that: the heirs sign a confidentiality agreement; the mobile home issue be ignored and all Kelly's lawyer fees be paid by the estate, as rendered by the lawyer, without question or challenge by the beneficiaries.

There does not appear to be any requirement that interest will be paid on the $145,000.

The heirs were put in a difficult position. They could make public the issue of $145,000 being removed from Thibeault's personal account, but at risk of losing that money forever or facing a prolonged court battle, which would rack up additional lawyer fees. If they were unsuccessful in a court battle with Kelly, the heirs would not get the additional money, and the charities may not get anything at all.

According to people familiar with the negotiations, that's where things now stand. Kelly is agreeing to the $145,000 being held in escrow until the heirs sign the confidentiality agreement. After both sides meet the terms of the agreement, the money will be returned to the estate and Kelly will step down as executor.

While this agreement may be satisfactory to some of the heirs, they have no authority to bargain in the names of heirs who have not been notified that they are named in the will---that is, the charities, which to this day have not received any payment whatsoever from the estate.

Under the terms of the agreement, the potential value of the estate will be decreased, because the value of the lost trailer will be ignored and because increasing, and unquestionable, lawyer bills will be paid by the estate. The charities have agreed to neither item, but will receive less money because of the agreement.

The probate process is designed to provide full public accountability of an estate, and to ensure that the wishes of the deceased, as expressed in the will, are carried out. The executor is a trustee of the estate---entrusted to carry out those responsibilities with reasonable speed and with strict adherence to the Probate Act and will.

But because lawyers are haggling over $145,000 that Kelly removed from Thibeault's personal bank account, the estate remains open, seven years after she died. Peter Kelly has betrayed Mary Thibeault's trust.

For additional information on this story. Click here.

Tim Bousquet is the news editor at The Coast. Follow him on Twitter @tim_bousquet.