The supposed Mayan doomsday prediction is complete nonsense. The Mayans used at least three calendars, only one of which ends on December 21, 2012. And that calendar “ends” this week in exactly the same way that our calendar ends on December 31—true, the 2012 calendars become worthless, but you simply start a 2013 calendar.

Moreover, there’s no evidence whatsoever that the ancient Maya themselves predicted any looming apocalypse—the “end of the world” read was imposed on them in the 1960s by an otherwise respectable anthropologist named Michael Coe. Coe’s musings were enthusiastically embraced by the New Age movement, and here we are today. Modern Maya, incidentally, either are unaware of the nonexistent prediction, are offended by it or are attempting to cash in the foolishness of the folks to the north.

Really, Mayan apocalypses are kind of boring. And since The Coast is a local weekly, we’re not much interested in exploring those other planet-ending apocalypses: where’s the local angle in an Earth-shattering asteroid hit or a solar system-swallowing black hole?

The real fun is in looking for Hali-pocalypses, the end of the city, as opposed to the end of the world. We found two versions that stand out as distinct, if unlikely, possibilities.

Super-tsunami

In 2001, geologists Steven Ward and Simon Day published an article entitled “Cumbre Vieja Volcano—Potential collapse and tsunami at La Palma, Canary Islands” in *Geophysical Research Letters*, a respectable, peer-reviewed journal published by the American Geophysical Union.The authors outline their concerns about the western-most flank of the volcano, a 2,000-metre peak in the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago off the coast of Africa. Ward and Day worry that a future volcanic eruption could send the entire flank—a slab of up to 500 cubic kilometres of rock, 25 kilometres long, 15 kilometres wide and 1,400 metres thick—collapsing into the ocean, all at once.

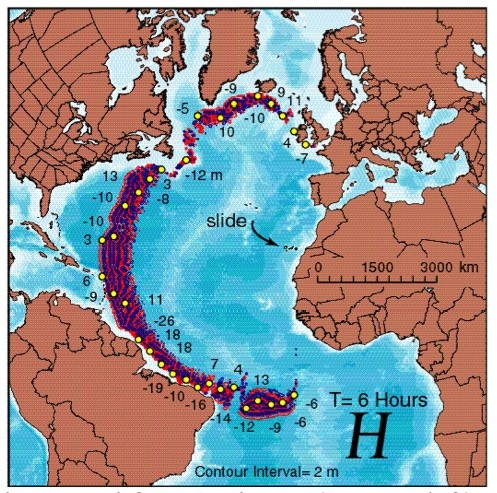

The two scientists then model the size of the multiple tsunamis such a collapse would create. Within two minutes, at the site of the collapsed block, there would be a “water dome” of 900 metres in height—taller than any building ever constructed. Five minutes later, and 50 kilometres out from the slide, the first tsunami would be 500 metres, about the height of the CN Tower.

At 10 minutes out, 250 kilometres in all directions, “several hundred-meter high waves have rolled up the shores of the three westernmost islands of the Canary chain.” But, they add, “the leading positive wave (200 m) is no longer the largest. Several negative and positive ones two-three times larger trail behind.”

Ward and Day track the super-tsunamis across the Atlantic, to Africa, to England, to South America and to us, in Halifax. Their map shows waves up to 13 metres high slamming ashore here about six-and-a half hours after the collapse. The good news, such as it is, is that waves that hit here won’t be as bad as the 25-metre waves that hit Florida.

A 13-metre wave in Halifax harbour would hit at about the fifth or sixth storey level of Purdy’s Wharf. Six or seven of such waves would likely destroy everything along the harbour, and a good ways up the hills on each side: all of downtown Dartmouth, the Bedford Highway, Bedford itself, the legislature, city hall, the bank buildings, the ports, the shipyard, the navy bases...

Hopefully, with more than six hours’ notice, the immediate death toll would be minimal. But the dollar cost is simply unimaginable. The Nova Scotian government couldn’t possibly afford the billions of dollars for rebuilding, and with such damage all along its Maritime provinces, the federal government wouldn’t be in much better shape. And since the waves will have also hit New York and every other large oceanside city, it’s doubtful the insurance and finance industries would even exist, much less provide any assistance to Halifax.

In such an event, it’s hard to see how Halifax survives as a city. Perhaps some small number of people could eke out an existence here, but most people would find themselves refugees, going from camp to camp or couch to couch, far to the west, until they can get settled into productive lives in a city that still stands.

How likely is the La Palma super-tsunami? Other geologists have contested Ward and Day’s theory, saying that they’ve over-stated the size of the potential landslide. Ward and Day counter that there is evidence in the geologic record that these kinds of super-tsunamis have occurred before. We’ll leave it for the scientists to battle it out, but it’s important to note that even if a La Palma-generated super tsunami is a probable event, there’s no reason to think it’ll happen any time soon. Of course, there’s no reason to think it won’t, either.

Nuclear accident

For as long as Halifax has been a city, there’s never been a super-tsunami. There has, however, been a city-levelling Explosion, killing thousands of people and maiming thousands more. Something that has happened before could happen again.If, dawg forbid, there’s ever a repeat of the Halifax Explosion, it most likely will happen just like the first one, resulting from a horrible accident involving a foreign ship.

And the most potentially destructive foreign ships are the American and British naval vessels that regularly visit Halifax. It’s estimated that fully 85 percent of the American naval ships that call in Halifax are carrying nuclear weapons. And both the US and Britain have ships that are powered by nuclear reactors.

Last year, one of vessels in the problem-plagued British nuclear-powered submarine fleet visited Halifax, prompting Steve Staples, president of the Rideau Institute, to warn of potential catastrophe.

“If a fire spread to a nuclear reactor and even any of the potential nuclear weapons that could be on board, you could see the release of radiation like we had in Fukishima, Staples told the CBC. "Fukushima in Japan required the evacuation of a 20-kilometre radius around the reactor. That would require a half million people to evacuate Halifax within about a day's notice."

With Halifax’s history of city-wide destruction, why the heck are we allowing nuclear weapons into our harbour?

In fact, there’s an international movement called Mayors For Peace, which calls for mayors to declare their cities as nuclear-free zones. Hundreds of cities—including 97 cities in Canada—have joined the movement. Perversely, nearly the lone holdout in Canada was the mayor of the one city actually destroyed by a nuclear-sized Explosion: former Halifax mayor Peter Kelly refused to join.

There’s good news. Newly elected mayor Mike Savage is supportive of the Mayors for Peace movement, says his spokesperson Donna McCready, and Savage is now investigating what it would take to enlist Halifax. It may take a motion of council, and that would involve some politicking, but with a commitment from Savage, it seems a good possibility that Halifax will soon join the movement.

Of course, the Mayors for Peace movement is symbolic, and Savage doesn’t have the power to actually prevent nuclear-armed or -powered warships from entering Halifax Harbour. But symbolism matters, and making public statements against nuclear weapons is the first step to ridding the world of them completely. Until that day, we’ll just hold our breath.

Complexity collapse

It’s easy to envision lots of other doomsday scenarios—climate change affecting agriculture, pandemic diseases and so forth—albeit few of them would unfold with the instancy of a super-tsunami or nuclear explosion. And none of these scenarios are specific to Halifax.They mayhem would be global.It’s possible we’re coming up against what theorist Joseph Tainter would characterize as the collapse of our social complexity, and that all the doomsday scenarios are manifestations of our inability to figure out ways to address our problems that cost us less than they’d benefit.

To cite just one example, we’ve gotten tremendous advantage from building a complex economy based on fossil fuels, and now that the easy shallow oil deposits are running out, we’re using new technologies to get still more oil through fracking and deep sea wells. But that further complexity comes with huge environmental costs, including rising sea levels.

Some coastal cities, like Venice, Italy and New York, are investigating or building flood protection devices that would keep storm surges at bay. In New York’s case, the system will cost on the order of $20 billion, for at best protection for a century. That’s $200 million a year, the cost of doing business to protect many trillions of dollars in assets in New York. But for lesser cities like Halifax? Forget about it.

We’re doomed.