The dressing rooms in the Cole Harbour Place arena are long and narrow. The dressing room smells faintly of stale urine and sweat. The locker room is under the stands, the ceiling is slanted, giving the room a cramped feel. It doesn’t help that tonight the room is packed with men.

Todd Bengert is tall, wirey and looks younger than his goaltending stories suggest. Like the other men in the room, he’s wearing a black tracksuit, the unofficial minor league hockey coach uniform. He’s leaning on the wall by the door. The other men stare at him intently.

“Canada has cheap and easy access to ice. We have more kids on the ice more often than anywhere else in the world,” Bengert tells his audience of roughly 30 coaches from the Cole Harbour Bel Ayr Minor Hockey Association. “Our goalies should be a dominant presence in the game at the highest levels.” Bengert’s giving this lecture, then an on-ice training session, because he’s trying to help Cole Harbour fix a growing issue in minor league hockey: A goalie shortage.

“We have noticed over the last five years or so a significant decrease in the amount of goalies available for minor hockey teams in the province,” says Brian Wentzell, chair of the Hockey Nova Scotia Minor Council. It used to be that only the under-18 age group saw a significant drop in goalies. “But now it's moving down the line down to U15, U13 and even U11.”

Bengert would argue the reason for the drop-off is there’s been a disconnect in the way kids are taught hockey.

The harsh reality for goalies is that most hockey practices are not designed to improve a goalie’s skill set. Even in the NHL, the best hockey league in the world, hockey practice isn’t good for goalie development.

And if it’s happening in the NHL, it’s happening in minor hockey.

“I’ve seen coaches draw Jackson Pollocks on their whiteboards: Xs, Os and lines all over. And the most important part of the game is reduced to three words,” Bengert tells the coaches. “Shoot on net.”

Because only goalies are taught the fine mechanical details of the position, it means coaches who are not goalies may understand how to create scoring chances, but they don’t understand how to actually score goals. Often, the only way for Bengert to get his foot in the door to help goalies is to reframe his sessions as goal-scoring clinics. In other words, in order to provide the bare minimum for goalies—at extra cost to goalie parents—he first has to promise to help skaters get better at scoring goals.

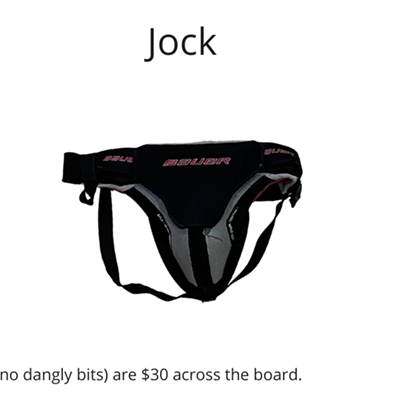

Not only is goalie development unfair, it’s also financially unfair. Hockey is an expensive sport. On top of the high cost of entry, goalies also eat the extra cost of goalie gear. To outfit a six-year-old in the cheapest new goalie gear available will run a family an extra $1,000, which is comparable to skater gear. But if that goalie grows up to play at the highest levels, the price of gear skyrockets and can easily clear an eye-watering $7,500 before taxes. Skater gear, by comparison, stays much closer to $1,000 as players grow into adults.

One of the details to emerge from the evisceration of Hockey Canada over its coverup of the gang rape allegedly perpetrated by up to eight unidentified members of Canada’s 2018 World Junior Team came from Colorado defenseman Cale Makar (who denies being one of the eight). He said his mom was disturbed to find out the money she paid in registration fees could have been used to brush the allegations under the rug.

Knowing that registration fees are misspent is not new information to goalies. Even though goalie parents pay registration fees the same as skaters, they usually have to pay for extra goalie coaching because, from the youngest age groups to the NHL, hockey practice is designed for skaters, not goalies.

Practically speaking, a goalie parent pays for the cost of skater development, while having to pay extra money for their own kid’s development.

Goalies are subsidizing minor league hockey for skaters.

“I say turn it around,” says Bengert. He points out that when a kid signs up for hockey, their parents pay $1,000 to $1,500 to register for the league, tryouts for competitive teams and conditioning camps. “What if,” he posits, “you throw them on the ice on the first practice, dumped a bunch of pucks in the middle of the ice and said ‘That’s it. We’re just working with the goalies the rest of the season?’ It would never happen.”

There's a pause.

"It would never happen."

And even though it would never happen to skaters, it happens to almost every goalie, almost every practice, almost every season. Even in the NHL.

“It’s not just that, it’s a double kicker. Now we’re paying for everyone’s development. We’re not getting any development. And my kid is the focal point for failure. He’s the focal point for failure, and he’s not being set up for success. Why would I continue? That’s why enrollment’s low.”

Todd Bengert is uncomfortably correct.

“There’s no way anyone in hockey gives a shit about the kids’ mental health.”

tweet this

“Parents can be awful,” says Cindy Schultz, the single mother of a goalie who almost made it to a career in the NHL. It’s not something she had to deal with, because her son was a really good goalie. But she remembers a time when she went to a game with her son’s billet mom. (Young hockey players who are very good frequently have to live in other cities or provinces to play at the highest level. When that happens, players are put up by billet families.)

A man sat beside Schultz at that game. “Pull the goalie!” he bellowed. “The goalie sucks!” he heckled. The goalie was playing poorly, and the team was losing. But the goalie was also a little girl. A child.

Schultz didn’t know anyone there and was furious. And then she found out: “It was the other goalie’s dad! They are on the same team! Are you fucking kidding me?”

Arenas are brightly lit; it’s very easy to see from the ice into the stands, and goalies have a lot of time to look around. The goalie—a child—was able to look up and see it was her goalie partner’s dad—a grown-ass man—who was heckling her.

What damage does that do to a child?

“When you are thinking about development and performance, when someone is a novice, then external pressure actually interferes with their [development] process,” says Lauren Marsh-Knickle, a psychologist whose practice includes mental skills training for athletes. Because playing goalie is “a tremendous amount of pressure; you're quite isolated in many respects.”

When a skater makes a mistake—takes a penalty or gets burned on a breakaway—they get to go off the ice. They get to skate off the stress of making the mistake. Nobody’s watching them, they can process their mistakes in private. They have teammates on the bench to build them back up. Coaches on the bench can offer words of encouragement or advice. Skater coaches have an understanding of skater positions, and skater coaches are more understanding of mistakes they themselves have made.

Goalies don’t have those luxuries.

It’s one of the downsides of goalies being treated like a specialized profession, a team within a team.

“I started to feel that even as a goalie coach, even if I was coming in regularly, there was a separation of my role. Then the goalies in conjunction got pulled apart from the team,” says Bengert the goalie guru.

Goalies need true support, says Marsh-Knickle. “Being told what they did wrong, or how they could have done it differently or better, is not helpful,” she says. In a position where conceding goals and repeatedly publicly failing is as certain as death, goalies must learn to love the game. And that is best done by reinforcing positive behaviour.

In the locker room meeting, a coach asks Bengert what to do if his goalie lets in eight goals in a game. “I don’t care if your goalie lets in eight goals; how are they playing?” Bengert fires back. The nature of the position means goalies will get scored on. If everyone on the team is developing like the goalie, the goalie will get scored on a lot. He tells the assembled coaches the important part of coaching a goalie is reinforcing what they do right, even if the play ends in a goal.

Marsh-Knickle encourages people considering goalie to learn how to incorporate a grounding routine into their game and to learn the advantages of breathing properly to stay in the moment and just enjoy playing the game. “When we encourage any athlete to have fun, they become better at their roles.”

Goalie mom Cindy Schulz says any attempt to create a real support system for goalies is good. When her son was playing in university, his team participated in “this Bell mental health bullshit.”

Bell Let’s Talk day is one day a year where hockey teams pretend to care about mental health. Hockey organizations take the day to publicly proclaim they care about mental health and are there for their players.

“There’s no way anyone in hockey gives a shit about the kids’ mental health,” says Schultz. She frequently had to take her son to Dairy Queen, bawling his eyes out because he’d been put on blast by a coach, teammate or parent for letting in “a softy.”

Frequent mental health emergency trips to Dairy Queen were something Schultz never factored in when she was budgeting for minor hockey. It is one of the many additional expenses goalies have as a barrier to entry. Since most hockey practices from the NHL on down are not designed for goalies, goalie families have to pay for extra training on and off the ice. Since the goalies are isolated from the rest of the team and under extra pressure, there is frequently the extra expense of mental health care at $210 a session.

Her son is happily out of hockey now, he's 26 and started a PhD in economics this year. But the financial hardships still linger.

“There was one year where he was supposed to go to a Quebec tournament for PeeWee. It was so expensive,” says Schultz. “We had no oil in our furnace, and he needed new skates. And I said, okay, you can either get new skates, you can go to Quebec, or we can have oil in the furnace.” They went to Quebec and relied on baseboard heat and blankets. "To this day, his toes are kind of bent.”

“If we do this right, in 10 to 20 years, goalies will start booming out of Nova Scotia, and Cole Harbour specifically, and no one will know why.”

tweet this

What Cole Harbour is trying to do this season is a bold new direction for minor hockey, even though it shouldn’t be. Cole Harbour’s minor hockey association is trying to put a goalie coach on every team. Not just as someone who comes out to practice. A coach at every practice, on the bench every game, advocating for the goalies. Defending the goalies. Supporting goalies. Explaining the position to head coaches who might not understand it.

Cole Harbour is trying to fully reconnect goalies into their hockey teams. Bengert is confident it will work. It seems like such a no-brainer it’s mindboggling that it has taken this long to even be tried.

But a half-hour drive further along along the coast, the Eastern Shore Minor Hockey Association has brought Bengert out once a week, sometimes twice a month, for 15 years to teach goalies. A one-hour session, in prime time ice, open to any goalie. Even just one hour a week of dedicated support and practice for goalies has increased goalie registration on the Shore. For a while last year, there was a single classroom in Eastern Shore with seven goalies in it. Meanwhile, in the larger neighbouring Cole Harbour hockey association, there were three goalies in the whole organization at that age.

In a response to a research request for this story, inGoal Magazine managing editor Kevin Woodley speculated about the future of Canadian goaltending. “I’m curious to see what happens with Canadian goaltending without Price." Carey Price, the longtime Montreal Canadiens stalwart between the pipes, is arguably the best goalie Canada has produced in the modern era and arguably one of the best goalies to ever play the game, but his career is ending. “He was the one most kids pointed to as wanting to be like,” says Woodley. “Not sure we have one of those anymore in Canada.”

Todd Bengert is wrapping up his lecture in the cramped, bright red dressing room. The room is warm now, so the locker room smell is now thick enough to taste.

“If we do this right, in 10 to 20 years, goalies will start booming out of Nova Scotia, and Cole Harbour specifically, and no one will know why,” concludes Bengert.

Except we will know why. It will be because a minor hockey association decided to give a shit about its goalies.

Normally stories like this end with a poignant conclusion and leave the reader to consider the implications of what they have just read. The above paragraph would have been a perfect place to stop. But this story needs disclosure. I am and have previously been a goalie coach. I discovered this program because I volunteered to be a goalie coach for my kid’s team when his teams are old enough to have a goalie. However, after doing interviews for this story, and reflecting on my own horrid time as a goalie in minor league hockey, I have volunteered to be one of the goalie coaches in this program. And I intend to continue volunteering with this program as long as it exists, even if my kid stops playing hockey.