There’s an old saying that goes, “You can have it fast, you can have it good, you can have it cheap: Pick two.” There’s a similar conundrum with the city’s plans to build a new network of bikeways in the south end. The city has put forward a number of design concepts, all with different trade-offs. It seems you can have bike lanes, ample space for parking, and preserve the city’s urban trees: Pick two.

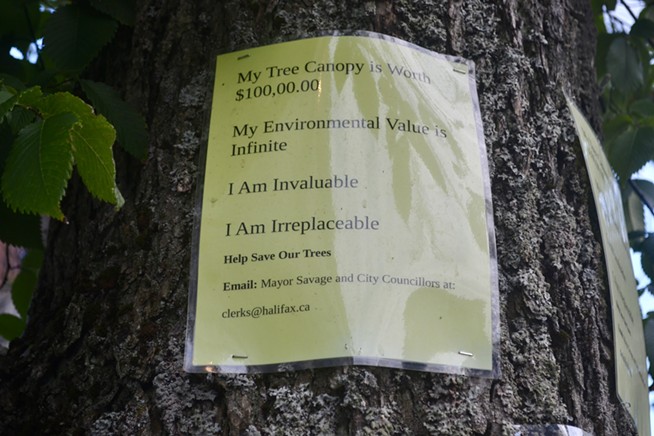

Karen Mitchell and fellow members of the community group Friends of Historic Schmidtville picked trees. The group has posted “save our trees” signs around the south end, and Mitchell started a petition that has almost 1,000 signatures. And there are those who stand up for the bike lanes, such as cyclist and sustainable transportation advocate Ben MacLeod. Mitchell and MacLeod were both featured in a Global News story earlier this month, and both say the debate has been misconstrued.

“I've looked at the comments beneath those kinds of news stories, and in presenting the situation as being cyclists versus trees, the Friends of Schmidtville have been very successful at generating a lot of anger and blanket opposition towards the bike lane proposals, which makes it quite difficult to have an informed and constructive conversation,” MacLeod says. And the Schmidtville group’s website reads, “Some politicians and media outlets and assorted mischief-makers try to set one group against the other.”

The issue at hand is in fact more nuanced than bike lanes versus trees versus parking. It’s bike lanes versus trees versus parking versus emergency access versus transit capacity versus loading requirements versus motor vehicle traffic versus pedestrian safety. And finding a balance between all these factors is where things get a little messy. Everyone has a different idea of what should be prioritized. As Mitchell says, “You’re not going to please everybody.”

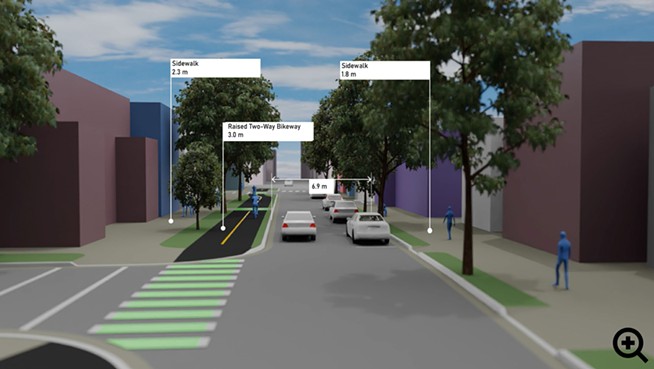

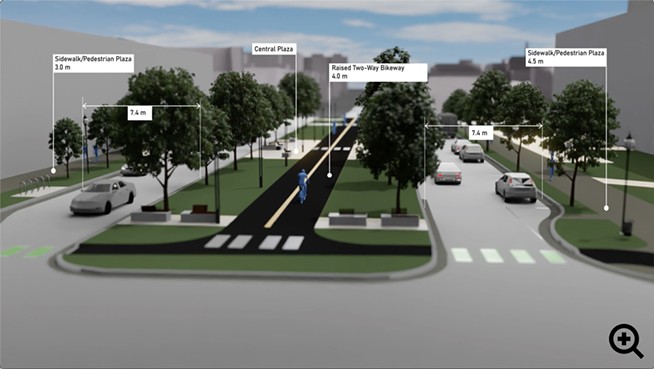

For its Peninsula South Complete Streets Project (part of the Integrated Mobility Plan), city planners have narrowed down eight design concepts from the original 15 after the first round of public engagement in 2019. There’s one option for Morris Street, three for University Avenue, two for Robie and two for a connection using either South Street or Cartaret Street and Oakland Road. The designs include varying degrees of parking loss and changes to the roads. And depending on which combination of concepts the city chooses, between 36 and 125 trees in the area could be on the chopping block. Most of the endangered trees are on University Avenue—between 23 and 56 of the street’s total 326—because all three of the options for the street require shifting the curb.

That’s not a small number. And trees aren’t a small issue in our city. “When it comes to this day and age of climate crisis, the last thing we want to see is a tree removed, because we need every single tree we have,” Mitchell says. And the trees in our city, and the canopies they create, are “fabulous.” It’s no surprise that Halifax has been named a Tree City of the World by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations for three years in a row. Trees do wonders for the environment, absorbing dozens of pounds of CO2 per year, preventing soil erosion and reducing noise pollution. Trees even make streets safer and increase property values.

Mitchell lives on Morris Street, where six trees are slated for removal. Two of those trees are elms that are at least 100 years old. One is right outside her window. “I get up in the morning and the tree literally replenishes me for the day. It’s beautiful,” Mitchell says. “But it would come down and it breaks my heart.

“I mean, just the profound sadness and tremendous outpouring of anger about the trees and Public Gardens, and that was 30 trees. So I don't care where those trees are, to me it's an act of vandalism to take down a very mature healthy tree.”

A safe, cohesive cycling network in our city would also do wonders for the environment. According to a 2016 survey by Simon Fraser University, 80% of non-cyclists said they’d be more likely to cycle in the future if more bike infrastructure were to be built in Halifax. And 58% of survey respondents said they were interested in cycling but concerned about the safety of it.

“If we want to reduce our environmental impact, we have to see a shift toward sustainable modes of transportation such as walking, cycling, transit,” MacLeod says, “and we won't see substantial uptake in cycling unless it's safe and easy for people.”

He says there’s also a social justice component “in that people with lower incomes own cars at a lower rate, and they use bicycles as a primary form of transportation at a higher rate. So right now in Halifax, we prioritize cars but we should provide safe cycling options as well.” And, MacLeod points out, motorists should naturally want this too because more cyclists means fewer cars on the road.

The cyclists and Friends of Schmidtville aren’t diametrically opposed. “Cyclists included don't want to see urban trees removed, and I believe the cycling community has been saying this all along,” MacLeod says. And while Mitchell isn’t a cyclist, her daughter is. “It's not about not having bike lanes at all,” she says, “it would be nice if we had a little banner that said ‘yes to bike lanes, no to trees down.’”

Where the two diverge is what the alternative should be. What should be sacrificed instead? For MacLeod, it’s parking and vehicle room. “Before the city looks at removing trees, particularly mature trees, they should really be looking at opportunities just to reallocate the existing road space from being dominated by cars to be more balanced between bicycles and cars,” he says. “Our streets are overwhelmingly dominated by cars and they're overwhelmingly built for cars. So what cyclists are asking for is not really that much.”

Mitchell disagrees. “Sadly in Halifax there is very little room for parking. So all you're doing is trading up parking for bike lanes,” she says. (MacLeod has counted the parking spaces in the Spring Garden area, and there are approximately 2,280 of them.) And while she rarely drives, she’s doubtful changes on the road will translate to changes in habit. “You don't just change people. ‘Oh, well we're all gonna abandon our cars and get on bikes?’ I don't think so.’”

“Maybe people don't quite recognize Halifax as a big city yet, but in big cities it's not always easy to park directly in front of your destination. I think people need to accept that downtown Halifax is not Dartmouth Crossing; there's not going to be a plethora of giant parking lots everywhere,” MacLeod says.

Mitchell suggests the city should put bike lanes on Clyde Street or South Street instead of Morris. “Why Morris Street? Poor little Morris Street? It’s Historic Schmidtville. It's busy as it is already. Leave the bike lanes out of it. But they’re not going to listen to us.”

MacLeod says South Street is too steep, and both Clyde and South are too indirect. “If the city wants people to use the future bikeway network, the routes have to be direct, because cycling is a mode of transport. It has to get you from point A to point B with minimal confusion and without unnecessary detours. And it also has to be legible. It has to be easy to navigate,” he says. “Why do we always force pedestrians and cyclists to bend around car infrastructure?”

“If there are ways to find routes for the bike lanes that don't make a huge impact on everyone involved, it would be better for everybody,” says Mitchell.

“I love where I live, but I'll tell you, if the trees go, I will too.”

For the city’s part, it landed on the option for Morris street—making it a one-way street with a two-way bike lane on one side and parking on the other—based on public engagement with residents, including the Friends of Historic Schmidtville. One of the project’s planners, Siobhan Witherbee, says Schmidtville residents wanted parking and trees prioritized, and they chose the design accordingly. “Unfortunately, there will still be some trees here and there that are impacted by these designs, but it's much less than in previous versions,” she says.

Witherbee says the city will replace any tree that comes down at least one-for-one, either on the same street or close by. And they’d be planted in soil cells “so they would have a greater opportunity to grow and thrive in urban environments because a lot of those street trees that get planted in the narrow boulevards don't have a lot of soil space to grow up big and tall, kind of like the old mature canopy that we're used to,” she says. And “succession planning,” or planting trees that are the same age, will create a “continuously renewing mature uban canopy in the long-term vision.” Witherbee confirmed those two 100-plusyear-old elms will be coming down, but that one of them is in “poor condition.”

The current concepts are only 30% designed, and so there is still potential for minor changes throughout the process—which could mean saving a tree or two, Witherbee says.

“We're trying to minimize the impact on trees as much as possible while still kind of fitting through some of the other objectives for this very high-demand corridor,'' Witherbee says. “It will really help people move around as it is built, but it's a little bit of growing pains in the meantime.”

The second round of public engagement for the project wrapped up in July, and now staff is writing up a report with recommendations for regional council, which will approve a design plan in early 2023. Construction of the bikeways is estimated to begin in two to five years.