Onna Young’s first memory of gender dysphoria is during a “puberty class” in fifth grade. “Everybody got to write down a question and have it anonymously answered,” she says. “Thirty questions went in the hat. Twenty-nine were answered, and I was held after school.”

Young’s question was about whether someone wanting to transition had to endure puberty as their assigned gender at birth. “I was just trying to access the very basic information,” she says. “This was the mid-’90s, so there was no internet to check.”

It was the beginning of “30 years of thinking about it in some way or another.”

Three decades later, Young was at rock bottom. Her father had just died, and the world went into COVID-19 lockdown. It forced Young to self-reflect. “You lose a parent and you check your own mortality, the time you’re wasting.”

Demonstrated dysphoria

In spring 2020, Young came out as a trans femme. First to herself, then to the people around her. By fall, Young was ready to come out to medical professionals. “It would’ve been September, I started trying to get my doctor to refer me to somebody and was blown off several times.”

In January 2021, Young gave up on her doctor and self-referred to the Halifax Sexual Health Centre, a sex-positive clinic on Bayers Road in Halifax that does everything from STI and pregnancy testing to safe-sex workshops. And like many trans people in the province, it’s where Young received the first in a long chain of referrals necessary to obtain gender-affirming care.

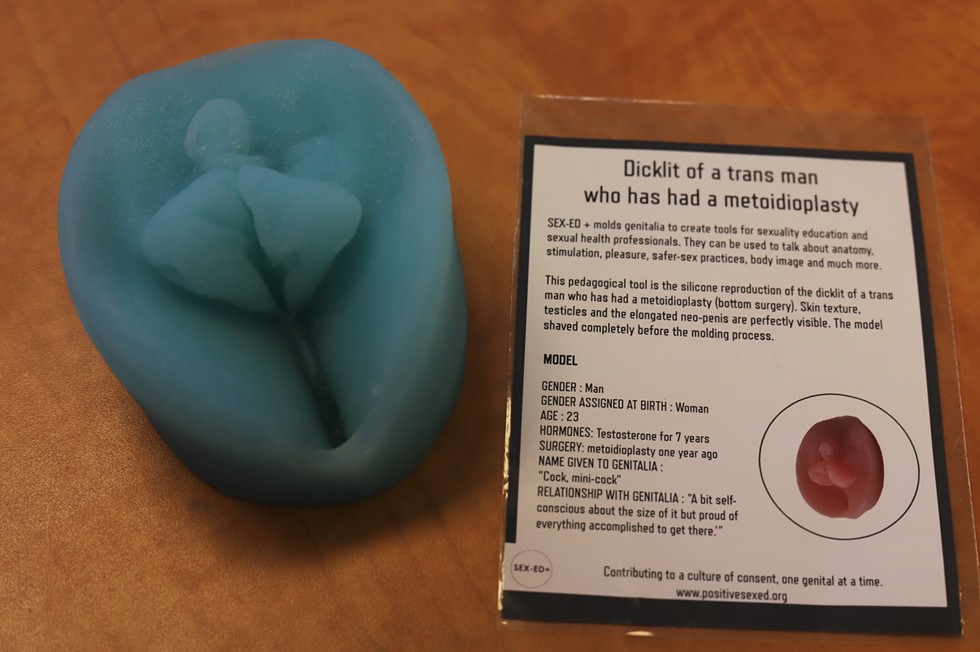

Gender-affirming care (GAC) for transgender, nonbinary or gender-nonconforming people includes everything from hormones like estrogen and testosterone, garments like chest binders or packers for the crotch area, and sometimes, but not always, top or bottom surgeries. Other GAC includes facial feminization surgery, vocal training or surgery, or permanent hair removal. But everyone’s gender-affirming needs are different—two trans women may need two completely different care plans.

In Nova Scotia, a mental health readiness letter is required for a trans person to get on hormone therapy, and it must be written by what’s known as a WPATH professional—a counsellor, psychologist or psychiatrist accredited by the World Professional Association for Trans Health. According to the WPATH website, there are 18 qualified practitioners in Nova Scotia, 10 of them in HRM.

To get the WPATH letter, individuals need a referral from a general practice doctor (not necessarily their own—they could self refer to the HSHC like Young did). After the WPATH letter, people who want gender-affirming surgery need more referral letters. Top surgery requires one additional referral from a specialist like an endocrinologist or surgeon and bottom surgery requires two referrals.

The HSHC staff told Young to expect a call within the next few weeks, putting her on a path to receive hormone therapy by the end of 2021. But it was the start of a much longer wait.

Riley Nielson-Baker hopes one day, trans people will have an easier time accessing GAC in Nova Scotia. Over the past year, Neilson Baker, a trans and nonbinary public administrator and Masters candidate, has developed a policy that would make Nova Scotia the most progressive province in terms of trans healthcare.

“It started out as just a small idea,” says Nielson-Baker.

Unlike a government bill, Neilson Baker’s gender-affirming care policy could be adopted tomorrow by the sitting provincial government. Yukon is currently the most progressive Canadian jurisdiction when it comes to trans health. Instead of the Yukon legislature voting on it, the Yukon health and social services department amended existing policy to expand the list of gender-affirming care options covered. Nova Scotia already changed its own policy in a similar way in June 2019 when it decided to begin covering breast augmentation for some trans women, and then did so again in November 2020 when it decided to cover top surgery for nonbinary people. Neither of these policy changes required a bill to be introduced, discussed, voted on and adopted in the legislature.

Nielson-Baker’s proposed GAC policy for Nova Scotia would expand current provincial health care (MSI) coverage to include breast augmentation for more trans women. Currently, trans women on hormone therapy only qualify for breast augmentation if they fail to reach the “breast bud” stage of development. It would expand MSI coverage to cover other procedures like facial feminization or masculization surgery (FFS or FMS), and chest masculinization surgery that involves repositioning of the nipples and countouring mammary tissue.

The policy would also expand the province’s dedicated queer health service, prideHealth, and shift Nova Scotia from the WPATH model of care to an informed-consent model, meaning that as long as people are educated about the risks and benefits of GAC, they can receive it.

It would also see the number of “readiness letters,” reduce to one for any surgery. Right now, chest surgeries require one letter from a specialist, and bottom surgeries like vaginoplasty, phalloplasty or gonad surgeries, like a hysterectomy or orchiectomy, require two.

Neilson-Baker says readiness letters are a holdover from when trans individuals were “seen as people who have a mental illness.” For any other life-saving treatment, “you would not have to jump through this many hoops.”

The changes would mean more people paying less out of pocket, but exactly how much it would cost the province is unknown. MSI, Nova Scotia’s Medical Services Insurance run by Medavie Health, deferred to the provincial government, which declined to speak to The Coast for this article. Health department spokesperson Marla MacInnis says the department has seen Nielson-Baker’s GAC policy and is “reviewing it closely,” but did not say when a decision would be made.

Estimates from 2013, before the province covered any gender-affirming surgery under MSI, indicate that a double mastectomy came with a price tag of around $10,000, and bottom surgery was between $30,000 and $60,000 depending on the procedures.

Another cost would be the creation of five full-time and four part-time positions within prideHealth, which Nielson-Baker calls “discriminatorily underfunded.” Currently, only two prideHealth employees serve the entire province, and the latest data from Statistics Canada indicates that Nova Scotia has the highest proportion of trans and nonbinary individuals in the country, with more than 4,800 people indicating so on the 2021 census.

The adoption of the policy would mean the province’s trans healthcare model jumps ahead by decades overnight. But Lisa Lachance—the province’s first genderqueer MLA—is trying to make legislative changes as well, not just around GAC but also around wider issues including pronoun use on provincial documents and the Vital Statistics Act. Lachance and the NDP team have composed a three-page draft legislation, the Gender-affirming Health-care Advisory Committee Act, which would advise the health minister on enhancing coverage for and access to GAC.

Lachance says it’s important to have legislation like this discussed, but has more faith that Nielson-Baker’s GAC policy could be adopted long before the sitting government gets around to talking about gender in the legislature. The bill was introduced and given a first reading on April 6 and then added to a long list of other draft legislation. “Basically it sits there,” says Lachance. “And what you hope is the government will decide maybe they like the idea.”

Nielson-Baker hopes their policy can be adopted as early as the end of 2022. It already has support from more than 30 organizations including the Nova Scotia Nurses Union, Halifax Pride and Doctors Nova Scotia.

“We’re going to make a huge policy push with participation in Prides across Nova Scotia,” they say. “We’re planning a protest, a petition drive, direct action within the community to drum up support and really get eyes and attention on the issue, and show that this community wants this.”

Onna Young remembers how she hated looking at her pre-transition face. “I left the medicine cabinet in my teenage bathroom open and shaved in the shower,” she says. “So I never had to look in the mirror.”

It’s a story she prepared for her appointment with the WPATH professional to prove she had a “demonstrated history of gender dysphoria.” It’s one of four parts of what Young calls the “Are you trans? test,” along with being a legal adult, being legally capable of making decisions and being deemed mentally fit. Young says the most worrying part is that at every stage, “these people can stop you from this.”

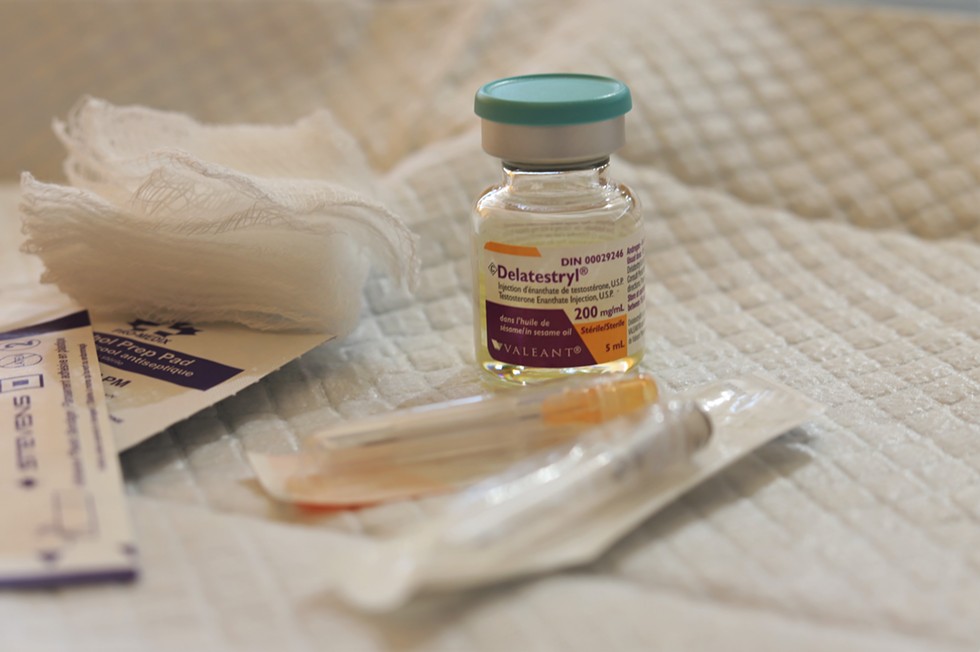

Young’s next step after the WPATH letter was an appointment back at the HSHC for bloodwork to figure out her current endocrine levels. Most trans women take estrogen and/or progesterone, but “it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution,” Young says. Because of provincial Pharmacare, Young will have coverage for the hormones themselves, but not for the injection supplies, which are about $50 a year from the HSHC, and are also available at pharmacies.

People who don’t have private insurance could face other costs. A 200 ml vial of testosterone is $75 for someone uninsured. It’ll likely last months, but costs like that have to be incurred for the rest of a trans person’s life. For surgery, the application form is clear that “take-home medications, equipment, meals and other personal expenses” are not covered by MSI. Gender-affirming clothing like packers, gaffs (tucking underwear) and chest binders aren’t covered by most plans, and even with Pharmacare and MSI, some aspects of gender-affirming care are never covered.

“There’s no billing codes for tracheal shave, which is a way of altering my voice,” Young says. “I do some vocal training, and there will be slight changes with hormones, but there’s no hormonal way to change my voice.”

Loren Baldwin, a Halifax-based nonbinary trans person, knows exactly what it’s like to be denied gender euphoria. But back in 2016, they lived in Toronto and thought of themselves as a cisgender lesbian woman.

“I was one of those athletic lesbians who lived in a totally tunnel vision world of the sports gays, and didn’t know many people who were trans,” Baldwin says. “There wasn’t much happening as far as nonbinary identities and there wasn’t a lot of space in the community that I operated in for others—for anyone who wasn’t a cis lesbian.”

Baldwin started experiencing gender dysphoria. Their chest didn’t feel like theirs anymore, their breasts just didn’t feel right. So Baldwin began looking into options. “I was Googling things like, women who get top surgery and women who aren’t trans men who get top surgery or double mastectomies but not for cancer. And the only things that were coming up were trans men.”

Even Baldwin’s doctors couldn’t help. “The language didn’t exist.”

Eventually, the chest dysphoria led Baldwin to get the only option available to them at the time — breast reduction. But the surgery didn’t stop the feeling of discomfort in their own body. If anything, it amplified it. The binder they’d been wearing maybe every weekend became something they wore every single day. “It really didn’t provide any relief.”

Six months later, Baldwin moved to Halifax, gender dysphoria still unresolved.

Hormones and holdups

Doctor Shirl Gee didn’t set out to be a trans health specialist. She came to Nova Scotia as an endocrinologist in 2001. “In my training in Montreal, there was very little exposure to trans health,” she says. But she agreed to take a few trans patients from a retiring doctor.

“And at that time, I would say the number of hormone providers was sparse,” Gee says. And it still is. Courses on GAC, hormones, PrEP and STI testing are offered to medical students through the Community-Based Research Centre, prideHealth and the HSHC—but they aren’t mandatory.

It didn’t take long for Dr. Gee to become the main endocrinologist prescribing hormones to trans people in Halifax.

When Gee, who’s now an assistant professor of medicine at Dalhousie University, hears from patients, they tell her the biggest obstacle is the wait time between referrals and specialists, but she says the new WPATH best practice document, set to be released this year, will likely reduce the number of surgery readiness letters to just one (the same thing Nielson-Baker’s policy does).

Her waitlist is typically a year, and people must obtain a WPATH letter before seeing her. “When I see people for hormone therapy, they’ve already had their assessment, they’ve waited.”

Gee says many trans people are further traumatized by having to repeat the stories of their dysphoria over and over. “Why do you need two types of people talking to the same person to figure out what they want?” she asks.

Waitlists for top surgery are expected to get longer and patients will now all have to travel to Montreal after the early May retirement of Steven Morris, who according to the Halifax Sexual Health Centre was the only provider of gender-affirming chest surgery within the province of Nova Scotia.

If fewer referral letters were required, people trying to access GAC might have shorter wait times. But Gee says allowing easier access for trans people would mean putting more demand on a system that’s receiving pressure from dozens of groups, each with their own special interests.

“There are cisgender women out there who could say, ‘Well, if a trans woman can get breast augmentation because of dysphoria, I experience a lot of social anxiety because of my appearance and part of it’s my breasts. Why can’t I get breast augmentation?’” Gee says. “I could see that can of worms.”

In April 2021, three months after Young had self-referred to the HSHC, she finally got an appointment with a mental health professional. The appointment didn’t explore anything that hadn’t already been recorded on her intake and referral forms.

“The exact same questions.”

Young’s appointment to get on hormones was booked for four months down the road, on August 18, 2021. “I had booked the whole day off.”

Two hours before the appointment, her phone rang. Cancelled. Rebooked for a month later. Young finally got her mental health assessment with a WPATH professional nine months after she first started trying. It took another six weeks for the referral to be faxed.

“There’s a certain point where you have to give up on thinking of it as incompetence,” says Young. “And have to assume it’s malice.”

“We don’t like being gatekeepers; that’s not a fun role for us,” says Abbey Ferguson, executive director of the Halifax Sexual Health Centre. “But so much of it is systems-based, and we have to work within those systems.”

All of the centre’s services could be delivered by a primary care provider like a family doctor. But since family doctors aren’t always receptive or educated about GAC, the HSHC is the main place people seek out gender-affirming care.

Right now, the centre has about 850 trans, nonbinary and gender-nonconforming patients who are having progress appointments for hormone therapy, usually every three months. There are about 50 people on the centre’s waitlist, and the five physicians take one new patient each month, so the current wait time is about 10 months.

“Our wait times, obviously we hate them,” Ferguson says. “It’s not fun for us to be like, ‘you have to wait 10 months.’ When you think about it in the context of people’s full lives, by the time that you realize that medical intervention might be something that you’re interested in, that could be your own years-long journey.” Comparatively, the wait for bariatric weight-loss surgery is about one year and seven months, and the wait for breast reduction is three years four months.

Ferguson says there are many challenges for the HSHC, mostly in terms of funding but also in terms of capacity. If the province shifts to an informed-consent model, as Neilson-Baker’s GAC policy proposes, mental health evaluations could be done by in-house social workers or psychologists who aren’t WPATH qualified. But Ferguson worries the HSHC’s waitlist would get longer if it added another service, and the already underfunded centre couldn’t afford an in-house social worker.

Ferguson, who’s been at HSHC for five years now, says access to gender-affirming care in Nova Scotia still has a long way to go. “I think informed consent is definitely a much more positive model,” she says. “You just want to give folks lots of opportunity to explore their gender identity.” Ferguson says with all its letters and referrals, the current model is “almost like gatekeeping to avoid having people detransition.”

A 2015 survey of almost 28,000 people from the American National Center for Transgender Equality found that only eight percent of respondents reported detransitioning, and 62 percent of those people eventually transitioned again.

Ferguson thinks better training for medical students is essential, “so that folks aren’t getting out into the community as primary care providers and then being shocked when they realize trans folks exist.”

Loren Baldwin was still dealing with gender dysphoria when they moved to Halifax in 2018. They’d gotten their breast reduction surgery in Toronto, but it didn’t fix anything. It wasn’t long before Baldwin realized Halifax was “queer in a way that I hadn’t known before.”

They met nonbinary people for the first time; people who got their breasts removed who didn’t necessarily identify as trans men; people at every point on the gender spectrum. Baldwin started to realize they were nonbinary. “It was really lovely and beautiful, but a few months too late,” they say. “I just went through this major surgery.”

It took two more years for Baldwin to come to terms with the fact that breast reduction didn’t get rid of their gender dysphoria. They finally made an appointment at the HSHC. “I think I want to start this process of top surgery,” they told the doctor.

From there, it was a repetition of what they’d already gone through in Toronto.

“All of those boxes you have to check in order to be approved by Nova Scotia seems unnecessary to a certain level,” they say. “I had to have a letter from Dr. Williams at the Sexual Health Centre, I had to have a letter from a psychologist or registered social worker.”

The second time around didn’t prove any easier navigating the system. “I felt like I’d already been waiting for so long,” Baldwin says.

The WPATH letter required a three-hour session that wasn’t covered by MSI, because psychologist and counselling appointments never are. “So I would have to pay out of pocket,” says Baldwin. The recommended rate from the Association of Psychologists of Nova Scotia is $210 an hour.

And while Baldwin got a surgery approved in Nova Scotia that wasn’t available in Toronto six years ago, the system is still slow to catch up to the existence of nonbinary individuals.

“We currently don’t have coverage for gender diverse people. All the surgeries covered in Nova Scotia are for binary trans people,” they say. “So my pronouns weren’t on the form, and all the boxes that they were checking were saying female to male.”

Inside the system

PrideHealth is small but mighty. It’s considered a division of Nova Scotia Health, but right now it comprises one person: Garry Dart.

As prideHealth coordinator, technically their position is only four days a week, but Dart, a queer genderfluid person, works full time as the outreach person, policy writer, educator and everything else that’s involved in serving the health needs of all queer Nova Scotians—an estimated 10 to 15 percent of the province, or 100,000 to 150,000 people.

“I do pretty much anything you can think of with regards to 2SLGBTQIA health care,” says Dart. “That’s advocacy, that’s policy, that’s educating providers, that’s working on gender-affirming care provision and inclusivity, working on pronoun campaigns, working on Pride. I help with complaints processes. I do everything.”

Many trans people go through prideHealth for referrals to trans-friendly and inclusive doctors, psychologists and endocrinologists. There are still more people seeking care than there are providers. “Spots get filled up very quickly,” says Dart.

Dart still sees first-hand the cracks in the system, the places where specialist appointments and referrals are time-consuming annoyances, if not unnecessary hindrances. “The system itself is often incredibly slow to change for many reasons,” they say. “Especially without people in positions of power that are diverse members of the community.”

The healthcare system, like any system, is slow to change. In the meantime, more Nova Scotians are being added to GAC waitlists than taken off it. And most people who’ve dealt with the system agree that it needs a revamp.

“It took nine months from getting a letter saying I’m allowed to do this, to actually getting someone who can write me a prescription,” says Natalie Lignin, a trans femme who went through the process of getting on hormones in 2020.

“All those people doing the gatekeeping are all cis, there’s very few trans people in this system,” she says. “Your body’s being policed by people who will never fully understand what it’s like to be trans.”

At some appointments, Lignin says she was more educated about trans health than the doctors she saw. “You need to go in really informed and know what you want and advocate for yourself,” she says. Lignin says family doctors shouldn’t be able to refuse to treat trans patients (another part of the system that Nielson-Baker’s proposed GAC policy would change). “I feel really insulted that doctors are allowed to be like, ‘no I’m not comfortable doing this,’” she says. “Like, if you’re uncomfortable about treating someone’s health, maybe you shouldn’t be a doctor.”

Lignin says despite the difficulties of having to navigate the system, it was worth it to experience that long-awaited gender euphoria. “When I got off the phone with the endocrinologist, I cried,” she says.

But she doesn’t want other people to go through the same thing she did. “Having to go see so many people and then just getting put on another waitlist and another waitlist,” she says. “It’s really convoluted and there’s no need for that.”

James Paynter is a trans man living in HRM who began his transition more than three years ago. Because his doctor claimed they weren't comfortable administering hormone therapy, Paynter self-referred and was given an assessment appointment for six months down the road.

“No one will ever be able to understand this unless you’re a transgender person,” Paynter says. “But when you’re given a date and the process is set to start on that date—you count on that date. You’re so excited to get the process started. It feels like there’s a huge weight lifted off your shoulders and there’s so much relief from the dysphoria."

But about eight weeks before Paynter’s appointment, it was cancelled.

“I was completely and utterly crushed,” he says.

It took six more months for Paynter to be assessed.

“With all the blows that I endured trying to get this whole process started,” he says, “it felt like I was hitting a brick wall at every turn.”

If everything had gone right for Onna Young, she’d have started hormones last year. But instead, she picked up her prescription just last week, in early May.

On a sunny Tuesday, Young biked over to Agricola Street’s queer-friendly Boyd’s Pharmasave, where the culmination of the long chain of referrals was as easy as picking up any prescription. The estrogen will start to take effect in six to eight weeks, and Young has begun taking selfies every Monday morning to document the progress. “Now I can start the actual journey,” she says.

Being on hormones, for Young, means more mental space freed up to focus on other things, like gardening. But after the long road that began 16 months ago, she’s tired. The difficulty of and knowledge needed to navigate the system would be exhausting for anyone. For trans people who have already been marginalized by countless institutions created by and for cis people, it’s not unexpected, but it is disappointing.

“It took all my energy to fight with them over this,” says Young. “This is fighting for your life.”