This ethos could explain why Devlin was happy to work away in obscurity, building a catalogue of art from his bedroom desk in a Dartmouth group home for the last three decades, while the world thundered along outside his window. But Devlin of all people knows that sometimes, when your work is good enough, obscurity doesn’t last.

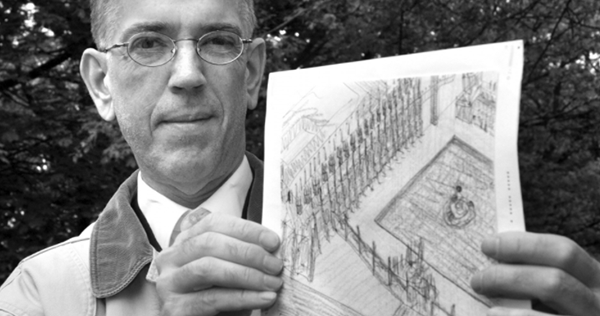

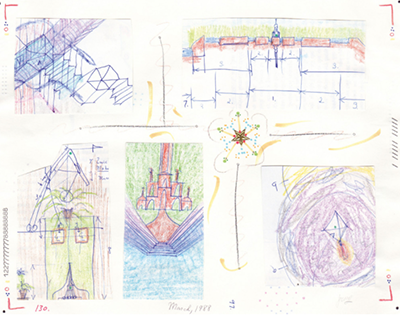

See, in the mid-1980s, Devlin had to put his life plans—studying theology in Cambridge, England—on ice indefinitely as he grappled with bipolar disorder. Returning to his family home in Nova Scotia, he put pencil to paper to recreate the paradise he had to leave too soon, sketching what he describes as “tests to design a utopia, based on Cambridge University, and put it in the middle of the Minas Basin”—a sort of superimposing of his two favourite places on top of each other, drawn with an eye for geometry and an architectural know-how.

And while he’s moved on from sketching maps of his version of paradise, these days opting for gold leaf-gilded artwork he describes as “more abstract and less consumed by the idea of a fantastical city in the Minas Basin, which is a bit a bit over the top, I guess,” it’s still mostly those early works—a series of output drawn between 1984 and 1988—that are gaining worldwide attention and acclaim. “I've gone on to do other things with my artwork, but for some reason a lot of people are attracted still to that series, the original drawings that I did,” Devlin says with an audible shrug. That first series contains what he estimates to be 365 drawings.

It’s been a fit of false starts to get here, plenty of playing to empty rooms before the crowd converged, as the saying (sort of) goes. “I kind of disappeared: I had a show in 1996, and then nothing more happened until 2012,” Devlin says, explaining that was the year a cold email to that London art dealer was met with enthusiasm and an offer to show works in Paris. Now, that dealer is part of a growing legion of Devlin fans worldwide, many of them museum curators and art critics.

It feels a long way from the quiet showing of sketches he mounted at Dalhousie’s TUNS in the late ‘80s, which was also organized by Cliff Eyland—the show he calls his start. Now, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia is purchasing four Devlin originals for its permanent collection (a rare feat for a living artist to pull off for even a single piece). In 2021 he’s also achieved what he called in an email to The Coast “a hat trick,” showing works as part of three international art exhibits in as many months. (Aside from the shows in New York and Berlin, Devlin has six pieces in the AGNS’s current show Making Space, open until September 26.) The momentum that’s been building since 2012 feels like it’s about to reach an apex for Devlin.

“I’m 66 now, so I’m a senior citizen,” he says. “It's been a real surprise. When I look back with some objectivity, it has been a great, great pleasure. The way things have turned around, which began with failure caused by my health, so long ago. And still, problems with health. And as I said to you, using the bipolar cycles: putting that to artistic purpose. And so, I harnessed my illness. That makes me produce art. So that's the bottom line, the whole raison d'etre of the whole thing.”

And while everyone else is just starting to explore the curves and edges of Devlin’s dream city, he’s moved on to a love affair with another urban landscape. “Halifax has the benefit of having grunge. I don’t listen to much grunge music but I love the idea of grunge, the damp, people in blue jeans,” he says. “The grittiness of a place like Halifax—which you don't get in Cambridge at all. It's more genteel. It's very prim and proper and rather snobby. I don’t like snobbishness.”