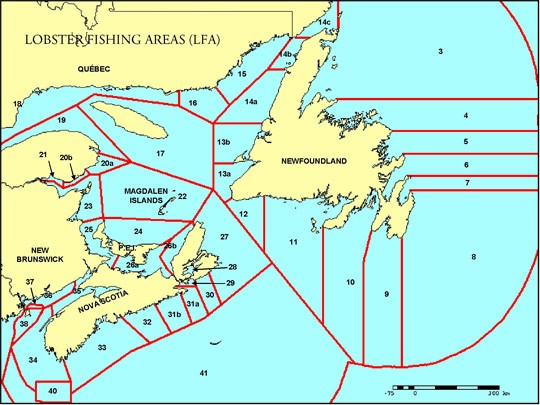

St. Mary’s Bay in southwestern Nova Scotia is full of lobster. It is one of the most plentiful spots within the most lucrative lobster fishing area (LFA 34, technically) in Canada. It is also—as its name suggests—a bay. Flanked by the long peninsula of Digby Neck and its islands, the bay’s long, narrow body of water is relatively calm and its depth relatively shallow compared to the larger fishing area it lays in. These qualities combined make it a very attractive place to fish.

Its resources are in high demand by Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers alike, and for more than 20 years it has seen tensions between the two communities turn from boil to simmer, to boil again. Recently, it made headlines internationally. Tensions in the area erupted into violence and destruction after the Sipekne’katik First Nation launched its own, self-regulated fishery, outside of the commercial season, based on Mi’kmaq treaty rights.

To Alex McDonald, one of the oldest still-fishing Indigenous lobster boat captains of the area, the chaos this year was nothing new.

“You know what, I've been at this so fucking long, two, three hundred non-natives come in to the wharf causing shit is nothing new,” he says. “I'm so used to it, I just brush it off ‘cause I know it's bullshit.”

Since he was a child, McDonald has been hunting and fishing under his treaty rights his grandfather introduced him to, long before today’s generation heard of the term “moderate livelihood” and even before the Supreme Court’s Marshall ruling in 1999.

Last fall—before the COVID-19 pandemic, before this year’s violence—I went aboard McDonald’s boat to see how he fished.

“The water’s flat as hell,” McDonald says in his gruff Boston accent, as he steers his fishing boat out to sea. The 43-foot, aqua-green boat named the French Lilly leaves Saulnierville wharf in St. Mary’s Bay. Its diesel engine chugs away loudly in the calm morning. A few snowflakes gently fall from the sky; some are caught by the boat’s draft and follow along for a moment before moving on.

McDonald follows his GPS to where he has laid his traps. He keeps an eye on the pixelated screen of his depth finder, looking for rocky bottom where lobsters like to live. “Inside that dip would be a good spot,” he says.

The French Lilly is McDonald’s seventh boat, fishing its fifth season with him now in November, 2019. He has been fishing for over 20 years. Before, he worked in construction doing drywall and masonry work, and spent a period of his life working around Boston—where he got his accent. He likes fishing more than construction, and he says because he has no bad habits he was able to save up enough money to buy his first boat.

The commercial lobster fishing season here isn’t scheduled to open for another 11 days, but McDonald already has traps soaking in the water. On the ocean’s calm, grey horizon, three other boats are seen fishing. Like McDonald, they are all Indigenous fishers who have the right to fish year-round. Some may be fishing to feed themselves, while others, like McDonald, are fishing to sell their catch.

Livelihood fishing has a controversial past. It has been a point of tension between Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers, with fisheries officers caught in between. It is a term created by the Supreme Court of Canada, which lacks clarity and has been left to stagnate. For over 20 years, McDonald has been navigating its murky waters.

In 1993, Donald Marshall Jr. of the Membertou First Nation was charged with fishing and selling eels out of season and without a licence. He argued that he had the right to do so, as stated in the Peace and Friendship Treaties, signed between the Mi’kmaq and the British in the 18th century. But he was convicted in provincial court. He appealed the conviction, and in September 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada acquitted Marshall of all charges, confirming his right to support himself.

The ruling stated: “The accused’s treaty rights are limited to securing ‘necessaries’ (which should be construed in the modern context as equivalent to a moderate livelihood).” It said a moderate livelihood is less than “the open-ended accumulation of wealth,” but more than barely scraping by, as “Bare subsistence has thankfully receded over the last couple of centuries as an appropriate standard of life” for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Many non-Indigenous fishers were outraged by the court’s ruling. Threatened by what they perceived as the unregulated access Indigenous people would have to the resource, they protested.

The West Nova Fisherman’s Coalition—a group of non-Indigenous, commercial fishers—applied to the Supreme Court for a rehearing of Marshall’s case. The motion was denied. However, in November 1999 the court offered a clarification of its initial ruling, stating that the federal and provincial governments had the power “to regulate the exercise of a treaty right where justified on conservation or other grounds.” Those other grounds include “compelling and substantial public objectives which may include economic and regional fairness,” but protecting the fishing stocks is the really important thing: “The paramount regulatory objective is conservation and responsibility for it is placed squarely on the minister responsible.”

That minister was, and is, the head of the federal department of fisheries and oceans, which is also called Fisheries and Oceans Canada, but universally known as DFO. In 1999, DFO was dealing with the collapse of cod stocks in the Atlantic and attendant criticism from both conservation-minded people and commercial cod fishers; the Marshall decisions publicly added another contentious issue to its portfolio.

The court handed DFO a loosely defined responsibility, its ambiguous boundaries marked by the Indigenous right to whatever a “moderate livelihood” is, and the government’s right to regulate that treaty right as long as it could claim to be acting in the interests of “conservation” or whatever “other grounds” it dared. In this legal grey area, the DFO had to decide how much fishing was too much.

At the time of the Supreme Court rulings, David Bishara was a detachment supervisor with the DFO in southern Nova Scotia. He’s no longer with the department. When we speak in 2019, he is working as a marine broker, selling fishing licences and quotas. Sitting in his office, a few family photos on his cluttered desk, his memories from decades earlier are strong.

“When the ruling came out, it was basically ‘OK, here we go,’ and ‘How is this going to be managed,’” Bishara says. “We knew there was going to be violence, we knew that there was going to be troubles between the native, non-native community; between the fishing industry and the native communities, it was expected by everyone.”

Bishara remembers feeling tension in the air like electricity, as Indigenous fishers slowly began testing the waters. In the year 2000, the tension reached a peak as both sides dug in. Indigenous fishers were going to exercise their rights at all costs, and non-Indigenous fishers in disagreement were going to try to stop them.

“That’s when the proverbial shit hit the fan,” says Bishara. “That’s when the violence, the extreme enforcement, the threats from the non-native community, the threats from the native community…that’s when everything erupted everywhere.”

Under pressure from the commercial fishing industry, the DFO stepped up enforcement. Indigenous fishers maintained they were within their treaty rights and pushed back. Alex McDonald was there, too, and remembers feeling like they were at war.

“They brought in the RCMP with fucking boats and everything. I mean they upped the forces big time,” says McDonald. “It felt like we were on a battlefield. It was stressful, it was fucking, oh it was miserable.”

One summer morning, Bishara, with a team of DFO and RCMP officers, was sent to make arrests of an Indigenous fishing crew for overfishing. It was McDonald’s boat, a predecessor of the French Lilly.

Video taken by the DFO captures the incident. DFO boats surround McDonald’s boat at the wharf. Indigenous fishers stand their ground, grabbing poles and wooden boards, daring the DFO to try and board. Chaos erupts: fists, bats, poles are seen swinging, and people on both sides fall into the water.

“I was one of the ones that went in the water,” says Bishara. As he went to grab a young Indigenous fisher, the operator of Bishara’s boat reversed in a panic, causing both Bishara and the fisher to fall into the water.

“And you know what’s interesting, is the young guy that I was supposed to grab, we grabbed each other but neither one of us wanted to do anything. Neither one of us,” Bishara says. “And I’m thinking, *thank God*. Thank God, because I didn’t want to hit him, I didn’t want to haul out my gun, I didn’t want to have to do any of that stuff. I didn’t even want to be there.”

The people who were arrested were taken to the Digby RCMP building. As things calmed down, someone brought in coffee to share. Everyone was offered a cup, except for one person. Viewed as a ringleader and an instigator, none of the officers would approach McDonald. Looking in the room where McDonald sat, Bishara felt bad for him. He gathered his lunch of meat, cheese and pita bread, and entered the room. He told McDonald who he was, that he was Lebanese and that he felt they had a lot in common; his family had also dealt with prejudice and racism. McDonald said he had worked with Lebanese people in the United States and liked them. Sharing Bishara’s lunch, they continued to chat.

After being part of many heated exchanges, Bishara could see first-hand that the DFO’s strategy of intense enforcement wasn’t working. He bypassed his chain of command and sent a letter straight to DFO’s regional director: He wasn’t willing to subject his subordinates to that level of violence and stress anymore. The regional director asked Bishara what he thought they should do.

“‘You’re starting from the top down, start from the bottom up,’” Bishara says he told the regional director. “Honest to God, all I could think about is what my father would have said, so that’s what I told him. He said, ‘Do you think we can do something?’ I said, ‘Give me a chance and we’ll see what we can do.’”

Sometime later, Bishara got in touch with McDonald, who had recently become chief of his band, the Sipekne’katik First Nation (then known as Indian Brook). He asked if they could meet. McDonald agreed. They met unofficially; Bishara didn’t involve any DFO “big brass.” He offered an apology and asked if they could start over. McDonald remembers this as the only time that someone from the DFO has apologized to him.

From that meeting, they agreed to remain in communication and to let each other know if they heard of any tensions that were arising. They would speak with their respective communities and try to calm things down before they had the potential to erupt into violence.

Bishara believes because of the cooperation they established, the blatant disregard and disrespect between the communities stopped. For a long period of time, the rough waters calmed, and the need for intensive enforcement disappeared.

Perhaps DFO “big brass” could have seen this detente as an opportunity to do the hard work of giving practical shape to the Supreme Court’s grey area. It was a chance after one predictable crisis to figure out how to avoid the next one. But the opportunity was wasted. McDonald and Bishara moved on from their leadership roles. What exactly a “moderate livelihood” looks like remains undefined.

Seeing the relationship between the communities regress into violence and destruction in the fall of 2020 would have felt like déjà vu for Bishara, had he not seen it coming.

"About seven years ago I started to complain to DFO that this was going to blow...and that’s exactly what happened,” says Bishara at the end of 2020.

After leaving the DFO, he watched from the sidelines as things turned into a “horrible hornet’s nest”. He says he saw DFO’s inaction lead to abuses of the Marshall decision. More and more lobster was caught without any management plan or regard for conservation and both Indigenous and non-Indigenous players cashed in.

“Non-native fishermen were involved, non-native buyers were involved, money was made by everybody, there were drugs involved, there was organized crime, god knows what else is involved," says Bishara.

At the wharf where McDonald docks, non-Indigenous fishers climb back and forth from the wharf to their boats, loading gear and making repairs in preparation for the opening of the season. In November 2019, They’re willing to talk about livelihood fishing, so long as their names aren’t mentioned.

“Then they’d burn my fucking boat. Geez man, they’d burn my fucking boat. We already had a boat burned here,” says one man. “I’ve done all this, I’ve been to the media, I’ve had the death threats and the phone calls. Come down here, they stole everything off my fucking boat.”

Tensions are already on the rise, pointing to where they will get to in the fall of 2020. A new generation of fishers and fishery officers is now having to negotiate the same grey area that their predecessors once dealt with.

“The senior advisors that were involved have retired,” says Bishara "The people that have come into fisheries and oceans since then don't have a connection with the communities. They don't have an understanding. They don't know the fishing culture, they don't know the fishing industry.”

The world has also changed since 1999. The technological advancements and political differences of today could be fanning the flames. A wave of right-wing populism has swept over the globe and racist opinions are more freely expressed. Internet groups and social media circulate uninformed opinions and misinformation, while algorithmically curated feeds of information relentlessly reinforce people’s biases, polarizing people. The willingness to understand one another’s communities and history could be shrinking, along with the middle ground needed for cooperation.

Non-Indigenous fishers are forced to the shore in the summer by DFO regulations, and watch from the wharves as Indigenous fishers haul in their catches. Some can’t help but feel like they’re watching helplessly as money is being taken out of their own pockets. Some argue that the playing field isn’t fair. But the most-voiced concern is for conservation, the subject given so much weight by the Supreme Court.

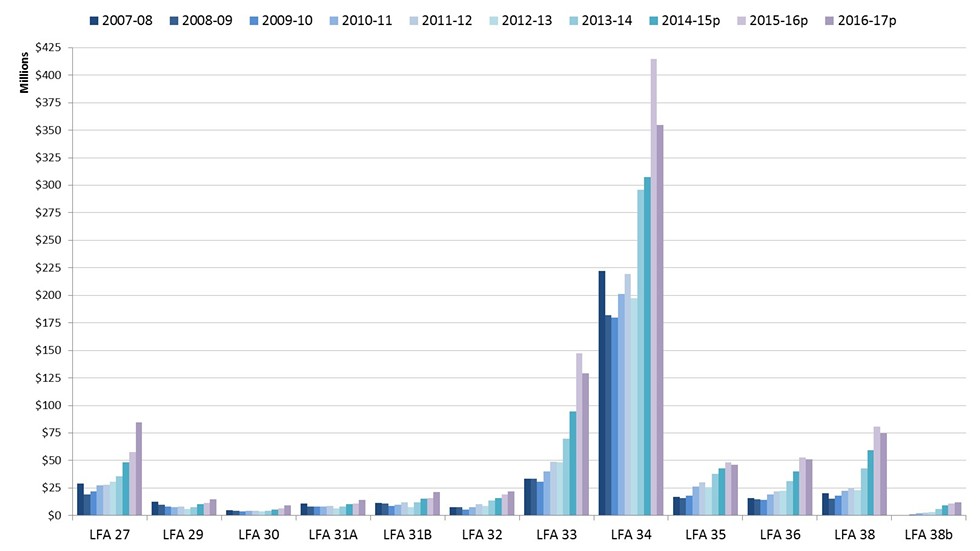

Because there has been no framework put in place for livelihood fishing, catches have gone unrecorded. No one knows exactly how many lobsters have been taken out of the bay over the years and what the long-term effects will be. Commercial lobster landings in LFA 34 have declined since peaking 2016, leaving many non-Indigenous fishers to blame the increase of out-of-commercial season fishing they see happening in the bay.

“It’s a big issue, they take more than a little of the stock. People don’t know what they take out of here in the summer. The trucks go by all the time. I see the crates, it ain’t good,” says one fisher. “It can’t take the 12 months a year.”

Biologist Aaron MacNeil, who specializes in fisheries, conservation and statistics, says it’s normal to see some fluctuation in the numbers. Though there has been a decline, he says it’s not yet nearing a point of concern.

“In St. Mary’s Bay the catch per unit effort is at 82 percent,” says MacNeil in the fall of 2020. Catch per unit effort is a measurement scientists use to judge the health of lobster populations. In LFA 34, it is based on catch amounts recorded by commercial fishers in their logbooks. This means last year the commercial fishery brought in 82 percent of its average yearly catch from the bay—based on a 20-year moving average.

The self-regulated moderate livelihood fishery launched by Sipekne’katik First Nation on September 17, 2020, was fishing 500 traps at its peak. Biologists have said the relatively small increase of traps being fished in the area won't have any adverse effects on the lobster population. MacNeil agrees and says it’s an easy claim to make when comparing 500 traps to the almost 400,000 traps fished commercially in LFA 34—even if the 500 traps are all fished in the smaller area of St. Mary’s Bay.

But more fishing happens in the bay than just Sipekne'katik’s livelihood fishery. It is fished by other bands including nearby Bear River and Acadia First Nations. And in addition to livelihood fishing, the bands fish food, social, and ceremonial licences as well.

“I think part of the confusion here is that there’re three fisheries operating in that bay. There’re the two commercial fisheries—Native and non-Native—and then there’s the food, social and ceremonial fishery,” says MacNeil.

The FSC fishery allows Indigenous people to be able to fish to feed themselves, their families and their communities. Unlike livelihood fishing, it is recognized by DFO who issue fishing licences and trap identification tags to the First Nation communities. Usually an individual band member can fish up to three traps all year round. But the FSC fishery was not created to provide income to Indigenous fishers and lobster caught under an FSC licence can not be sold.

“I often hear ‘you have no idea what’s going on,’” says MacNeil. “What they’re talking about is the size of the food, social, and ceremonial fishery. And they’re right, I have no data on that, all I have is the hearsay from the non-native fishermen that there’s something in the order of 8000 traps in that bay, and that could be possible. But from a scientific perspective it’s very hard to comment on that.”

According to the DFO, limits on FSC harvesting is negotiated between them and individual First Nations. When asked if FSC catches are recorded by DFO science, and if logbooks are used by fishers to record catches, like in the commercial fishery, a DFO spokesperson responded in an email:

“Commercial logbooks are not used to report FSC landings. DFO works with Indigenous communities to understand their FSC fishing needs and activities and to obtain catch monitoring data. Monitoring and catch reporting requirements are reflected in the conditions of the licence.”

MacNeil thinks there needs to be more done to understand what is really going on in the bay.

“There's just so much rumour and not enough science. I think what this conflict highlights, is that we have very little science going on for our most important fishery,” says MacNeil. “I think the time has come for DFO to put more resources into fishery-independent information about Nova Scotia lobster.”

More science could also confirm or dismiss some of the many claims that fishers make, such as St. Mary’s Bay being a lobster spawning ground. A theory that suggests lobsters migrate to the area to breed in the summer months is currently not supported (or dismissed) by any data MacNeil knows of.Another less-shared point of tension felt by non-Indigenous fishers is that the amount of lobster they catch goes down during the commercial season. Fishers catch around four to five kilograms per haul during the first few weeks of fishing, and within six to eight weeks it drops down to one kilogram. The main reason why is thought to be because the lobster haven’t been fished for several months, giving the populations a chance to grow. And it makes sense: There should be more lobster in the water before fishing starts, than after two months of fishing.

But this means commercial fishers are disproportionately counting on the money they earn from the higher catches landed at the beginning of the commercial season. Fishers who are heavily invested in the industry, carrying large loans with aggressive re-payment terms, fear the pre-season fishing they see happening is cutting into their earnings and is affecting their own livelihoods. Many fishers say they would be fine with livelihood fishing so long as it takes place within the commercial season.

David Bishara doesn’t think a separate Indigenous commercial fishery (like the one Sipekne’katik First Nation launched in September) is the way forward. He says having two different commercial fisheries with different seasons creates a double standard that will never work. It will only lead to more tension between the communities and he thinks things will get much worse.

He says he doesn’t dispute Indigenous people’s treaty rights, but thinks a balance needs to be met. Even though the DFO has so far failed miserably to meet the needs for Indigenous people, it’s still the DFO’s responsibility to step up and make a fishery that will work for everyone. He thinks if the government didn’t let things slide for so long the situation today could have been better.

"They've done an extremely poor job of managing it,” says Bishara. "It's just poor gutless bureaucrats and they’ve failed the rest of the country. The fishermen I know, on both sides, are good people and all want the same thing...they want a roof over their head, they want food, they want to share in the bounty, they want to provide for their families.”But McDonald says Indigenous fishers will always need their own time to fish; two months outside of the commercial season, away from non-Indigenous fishers will always be necessary. He says he has experienced harassment and vandalism of his gear even when he’s fished with a commercial licence during the regular season.

“They still cut your traps, they still ‘whoo whoo’ on the radio, they still cause shit at the wharf for being Indian, so either way it's very hard for us to fish amongst them,” says McDonald. “The prejudice is there, and it will always be there. You can't stop it.”

At the wharf, McDonald tries to maintain good relations by making it less obvious he’s been out fishing. When docked, all fishing gear is kept out of sight, to not rub it in that he’s fishing outside the commercial season. On this day last fall, it seems to be working.

“That green boat right there, he does everything like he’s supposed to. He was just here talking to me, I know him pretty good,” said another fisher. “He goes out once or twice a week. He could go out every day if he wanted to, but he doesn’t.”

A pungent smell, like sulfur and rot, wafts into the boat’s cabin. McDonald’s deckhand has begun preparing bait for the traps. He stuffs small mesh sacs with dead mackerel and herring.

“He don’t want to be mentioned and I don’t blame him. Keeps life simple for him,” says McDonald. “Let’s see if that single trap is there.” He steers his boat to what he calls his test trap, not too far from the wharf. Whether the trap is testing the lobster population or the DFO isn’t clear.

The deckhand spots the small buoy and points it out. “OK, good eye, good eye,” says McDonald. “The tide’s coming in too, so we’ll have to work fast.” The deckhand grabs the buoy from the water and wraps the rope it’s attached to around the wheel of the electric hauler. It pulls the line up with speed.

The trap emerges from the water. It appears to be in a state of decay, rusting and growing seaweed. About 10 lobsters are inside. “That’s a small catch, but this trap doesn’t fish well,” McDonald says. “It never did, that’s why we don’t care about it. They can take it if they want.”

The deckhand opens the hatch of the trap and quickly removes the lobsters, placing them in large plastic bins. The empty bait sack is replaced with a full one and the trap is dropped back into the water.

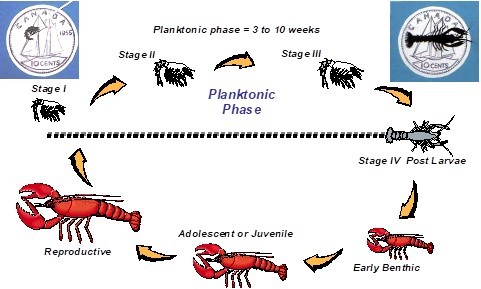

The lobsters are then measured, and the undersized juveniles are tossed back in the water. Female lobsters carrying eggs are v-notched and thrown back too. V-notching is a conservation technique used by lobster fishers—they cut a “V” shape into the lobster’s tail, harmless to the lobster—which notifies other fishers who might catch it later that it’s a fertile female who once carried eggs, and should be thrown back so it can continue to populate. Only the lobsters that are large enough, carry no eggs and are not v-notched are kept by McDonald and his deckhand. Rubber bands are put around their claws.

McDonald believes conservation is important. “There should be something put in place you know what I mean. A hundred percent, I believe that,” he says. But how could a livelihood fishery be managed, what would it look like? “It would look like the very first ones we did,” says McDonald. “I wrote them.”

Set far back from the ocean is the small white bungalow where McDonald lives. Inside, he makes a cup of green tea and sits down at his kitchen table with his take-out lunch of fish and chips.

Beside him on the table is a case thick with paper. He starts to fish through the documents, pulling out management plans, commissioned aquaculture studies and correspondence letters between his band and the DFO dating back to 1997. “We were fishing under that prior to Marshall,” he says.

Before Marshall won his case in 1999, members of the Sipekne’katik First Nation, who were confident he would win, drafted their first management plan to deal with livelihood fishing. The plan included trap numbers per boat, boat sizes and the minimum size of a catchable lobster. It outlined how the plan would be enforced, and how the band would work with DFO to enforce it.

(In the fall of 2020, I asked McDonald about the Sipekne’katik’s management plan that is currently being used for their self-regulated fishery. He said it looks very similar to these plans drafted years ago.)

But after the Marshall ruling, the DFO never agreed to work with any of the proposed management plans, and no new government framework was created to address the need for livelihood fishing. Instead, DFO tried to absorb First Nation fishing into the existing commercial fishery. A controversial buyback program was created by the government, benefiting many non-Indigenous fishers: Commercial licences were bought back from retiring fishers, as well as their used gear, at inflated prices. The gear and licences, as well as money, were offered to the First Nations communities in the Maritimes, in exchange for signed agreements that they would fish under the DFO’s rules. Many communities that were strapped for cash jumped on the opportunity. But some, including the Sipekne’katik First Nation, refused to sign.

Eventually the government gave Sipekne’katik a relatively small number of commercial licences. These licences are owned communally and leased by the band to fishers per fishing season. Sometimes they are leased to non-Indigenous fishers, which has been a contentious issue within the band. Though this system does bring back revenue to the band, the limited number of licences, and high prices they’re leased for, limits access to individual band members and falls short of meeting everyone's needs.

Commercially fished lobster traps need identification tags issued by the DFO to be attached to them. In November of 2019, McDonald fishes with no tags attached to his traps. Any traps without government-issued tags are un-authorized in the eyes of a DFO officer, as there has been no framework created to deal with livelihood fishing. (This year the Sipekne’katik First Nation has issued its own tags for its self-regulated fishery. But until it finds a place within the government’s fisheries act, their tags will remain un-authorized.)

If a DFO boat happens to find McDonald’s traps, they will be seized, and their catch dumped back into the water. If his traps are found by certain non-Indigenous fishers, the lines may be cut, making it very difficult for him to retrieve them from the ocean floor. If they are found by certain other Indigenous fishers, the catches may be robbed. “Sometimes we’re our worst enemies,” says McDonald.

So, to try and avoid all of this, McDonald’s buoys, which mark his traps, are small. They’re about the size of a softball and are dark in colour; on the ocean’s surface they’re virtually impossible to see from a distance. Other than randomly running a boat into one, they can only be found through the markers on McDonald’s GPS.

As McDonald approaches the area where he has laid his second set of traps, there’s a problem—he can’t find his buoy. He circles the boat around. “We’re only at 17 fathoms, we should see it,” he says. Because his buoys are undersized, sometimes they become submerged by the bay’s massive tidal swings, as the strong currents can hold them down. He circles his boat around his GPS marker, positioning his boat broadside between the incoming tide and where the buoy is supposed to be. This is a technique that’s supposed to block the push of the current for a moment, allowing the buoy to pop up to the surface. But it doesn’t.

“The DFO could have cleaned me out,” he says. Giving up on the lost buoy, McDonald steers towards his final line of traps.

But again, there’s no sign of his buoy. “We should be right on top of it.” He circles his boat around, nothing. Then a second time, still nothing. “Get the grapple, let’s do this shit,” he says to his deckhand. The deckhand hauls out a heavy box. I ask what it is. “A lot of work, that’s what this is.” From the box he pulls out something that looks like a medieval weapon. It’s heavy and looks to be made of cast iron; a cone, covered with hooks, about the length of a person’s forearm. Attached to a line, it’s dropped into the water and dragged across the bottom, about 20 fathoms down. McDonald is fishing for his own fishing gear.

Eventually the grapple catches something and the line becomes tight. It’s hauled up, and out of the depths comes a yellow trap in poor condition. Overgrown with seaweed, its line has been cut, but it’s not McDonald’s. Tangled up with the neglected trap is McDonald’s line, leading to the first of his 10 traps. “You see what we have to resort to, dragging this shit up!” The tangled mess of lines is sorted, and McDonald’s traps are hauled up one by one. The old trap is tossed back into the water. McDonald says that he doesn’t like the idea of adding more plastic into the ocean, but the old trap will create a small artificial reef, benefiting lobster and other sea life.

McDonald points to the buoy that was supposed to be on the surface marking his traps. It’s dark and small, not much larger than a clenched fist. One small part of the difficulties and dangerous tactics he has to endure, just to continue doing something he’s always had the right to do. “Cowboys and Indians, it’s the way it’s always been.”