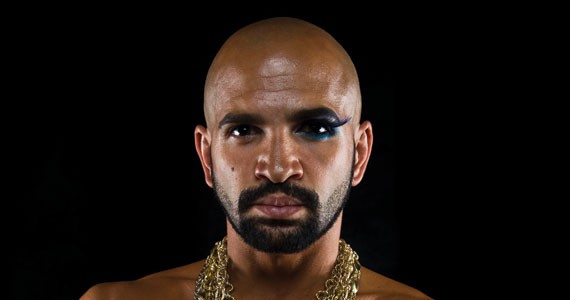

Odds are no one on earth has ever said "nigger fag" as candidly as Berend McKenzie. "I'm not one to sugarcoat things," he says. "If we ban those words, does that mean they don't exist? And if they don't exist, what happens to my stories of being called a nigger?"

The answer to that question is nggrfg (say it aloud), McKenzie's autobiographical one-man show, coming to the Queer Acts Theatre Festival next week at the Bus Stop Theatre. The play is made up of four stories, each examining what it's like to grow up black and gay in an Albertan community with little tolerance for either.

"I started writing from pain," McKenzie says. It sounds corny, but when he says it, you believe him. "Writing literally saved my life."

Yet he didn't start out a writer. Ten years ago, his goal was to move to LA to become an actor, "making movies and all that crap." And it happened: you can watch him exclaim, "Man sandwich! Twelve o'clock!" to Halle Berry 13 minutes into Catwoman.

"I found in that split moment my dreams came true—-that dream of being in a room where the director stands up and says, 'You're the guy! You're the one!'" But when producers found out that he's been HIV positive since the late '80s, he stopped getting roles: "In that moment, the rug was pulled out from under me. And I had no outlet. And I almost got out of the business completely, because I felt devastated."

That's when he began therapy—-a year and a half of delving into his shame over HIV, and his subsequent drug and alcohol abuse in the early '90s. When he needed an outlet, his friend and future collaborator, Darrin Hagen, told him to write. So he did.

His first full-length play was a puppet show involving a queer disco remake of The Passion of the Christ. "It forces me to come from an honest place," McKenzie says of his penchant for shock value. "It forces me to just get to the point."

He had his next play, nggrfg, all planned out: it would be four real-life stories. He would play every character, from himself at age seven to his mother and high school girlfriend. This onstage solitude is something that still terrifies him before each performance: "Before I step out onstage, there's that moment where I go, 'OK, if you mess up anywhere, the show's on you.'"

And he has messed up—-on opening night at Edmonton Fringe last August, he had a coughing fit, apologized onstage and called out for his line more than once. And when that performance received a standing ovation, he began to cry. "It's been an amazing journey," he says. "Every step in the process has been this sort of awakening... It's encouraging people to have a dialogue."

His latest venue has been the Vancouver school system. After debuting at Vancouver Fringe, the city's school board saw the show and decided to pick it up. He's since performed nggrfg in all sorts of schools, from secondary down to kindergarten. (And yes, for the latter group, he replaces "nigger" and "fag" with "black" and "sissy.")

McKenzie noticed that the kids understand the content in a totally different way, because "they're living it daily." And in some cases, they're the ones most affected, who need affecting the most. "I get the big buff jock kid that comes up with tears in his eyes, that can't really look me in the eyes, and doesn't really want to say thank you, but finds himself saying, 'Thanks man, thanks for the show. Thank you.'"