Armco Capital has a lot of work ahead if it wants to earn back the trust of Beechville residents for the company's new subdivision.

Helping ease the tensions built up from 200 years of false promises and racist planning decisions is Joachim Stroink, the former MLA who made national headlines in 2013 after posing for a Christmas photo with a man in blackface.

On Tuesday, regional council unanimously approved a motion to move forward with Armco’s subdivision proposal, provided the developer adheres to several amendments designed to preserve important heritage sites for

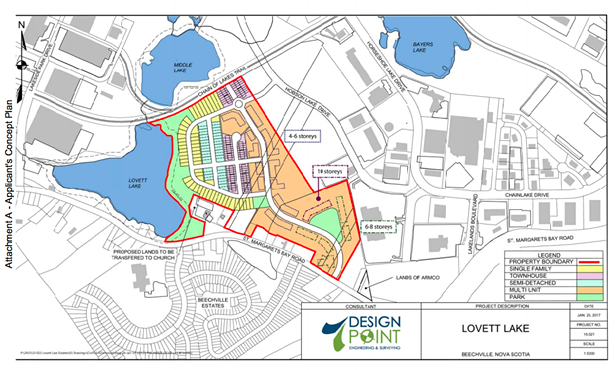

The developer is hoping to build nearly 1,300 residential units on land north of the St. Margaret’s Bay Road, between Lovett Lake and the Bayers Lake Industrial Park. It’s an expansion of a previously approved land-use agreement from 2014, and the latest battleground in an erosion of

Among the 2,000 Black refugees who arrived in Nova Scotia from the War of 1812, two dozen were granted a license to live on a 10-acre lot called Refugee Hill. Much like the Black Loyalists and Jamaican Maroons before them, the refugees were given small, rocky pieces of land considered of no real value.

The 1948 book, A Documentary Study of the Establishment of the Negroes in Nova Scotia, recounts how the original settlers were told that if their conduct was “industrious, peaceable and loyal” their land grants would be confirmed by the government. But deed and title never came, and as the community grew it was pushed back further into the woods to a 5,000-acre parcel that became known as Beech Hill (later, Beechville).

The residents made do with their lot. They built homes, farms and a school. Richard Preston founded the community’s Baptist church in 1844. But over the centuries a pattern of expropriation and land-use changes whittled away borders at the expense of heritage.

Watershed management caused a growing Halifax to expropriate several properties in 1917 and push Beechville residents further into county lands “for the preservation of the purity of the City’s water supply.”

Families were offered “groceries for land,” as one resident put it, to give up their properties. Huge chunks were carved off for the Bayers Lake and Lakeside industrial parks. An urban renewal scheme in the '70s forced Beechville residents to relocate to a single small subdivision after the city switched property zoning for their lands to industrial use.

Unlike Africville, Beechville wasn’t destroyed overnight, says former resident Carolann Wright-Parks when speaking to The Coast back in May. It took many, persistent planning decisions.

“I used to call it a high-tech bulldozing,” Wright Parks says. “Africville was bulldozed overnight. For us, it took several years.”

Given its history, the current residents of Beechville aren’t unsurprisingly

Armco’s previous development in the area, Beechville Estates, was built in the '90s at the protest of community members who felt their wants and needs were ignored, says Wright-Parks.

“There’s still a lot of bitterness around that process. You can say you can have consultations and all that, but who’s really to hold you accountable on the community side? The only real contract is between the city and the developer.”

The expansion of Armco’s newest subdivision plans came to council in May but was deferred by area councillor Richard Zurawski pending a supplemental report on its impact to the Black community.

As established in the motion approved Tuesday, the developer is now required to produce a Heritage Impact Statement for the Baptist Church, ensure the protection of the church’s property and heritage assets and work with Beechville residents through a newly formed community liaison group.

To help ease tensions, Armco has also hired former Halifax Chebucto MLA Stroink to act as a go-between. Stroink tells reporters his first meeting with community members last week was a “great first step” but there’s still a lot of work to be done in getting Beechville residents on-board with Armco’s plans.

“I want to hope that we can exude the trust that needs to come forward on this,” he says. “That’s why I’m playing a part of that role, is to really have that conduit of a relationship and listening to their needs.”

Stroink isn't an unknown to African Nova Scotians. The most infamous moment of the former MLA's political career came in

After meeting with the minister of African Nova Scotian Affairs, a teary-eyed Stroink held a press conference apologizing for the debacle.

“I do acknowledge that the whole blackface culture...there is no place for that in Nova Scotia, nor in our [Dutch] culture as well,” said Stroink. “There was no malicious intent whatsoever. This is a Dutch tradition that I grew up with and never ever in my deepest heart ever thought that this would be portrayed in this manner.”

He’ll now be working closely with Beechville residents to preserve historic sites like the Baptist Church graveyard. Staff are also asking the developer to integrate parkland and community uses into its new subdivision that honours the area’s heritage. Stroink says Armco will transfer the land it currently owns containing marked graves to the church, and incorporate the history of Beechville into signage and street names.

Who will live in those new homes is another matter. Planning staff are hopeful the subdivision will enhance the community without gentrifying it. Stroink suggests that still needs to be worked out.

“That’s part of the dialogue we’re having with the community—figuring out what the homes look like and the development looks like,” he says. “We’re still early stages of costing and all that stuff.”

City staff note in their latest report to council that no specific outcome can be guaranteed to either the Beechville community or the developer. The municipality can only commit to facilitating an open, transparent and collaborative process.