There is still a sheet of snow on the hills around Windsor, waiting for the brisk pull of springtime to shake it loose and blanket the countryside with lush greens, to start the cycle of life. As the road winds through the muted winter scene towards the farm, you see the green and yellow of the Quality Meats sign long before that last turn onto Sheep Farm Road where the Mike Oulton Meat Store, the home of Martock Glen Farm, sits.

The farm spans around 1,500 acres, a little under half is livestock farmland with the rest made up of an apple orchard and sprawling woodland and wood lot. Mike Oulton and his wife, Dianne, built the farm in 1963, opening the Meat Store in 1979. “It was a livestock operation, cattle and some sheep,” says Wayne Oulton, who runs the operation with his father and his brother, Victor, “and they started a slaughterhouse.” He returned to the farm after he finished college in 1997 and oversees the Meat Store with his wife, Nicole.

“Farming is in my heart. I couldn’t go to the city,” he says, laughing. “I wouldn’t want to commute to the city every day to work, so if we can make it work here that’s great. Farming provides a living and it’s a lifestyle, but it can be hard to thrive at it. People struggle to make a living for their family like what we’re doing, or what we’re trying to do.”

“We value the way of life,” says Nicole, who calls their five young children “free-range kids” with a laugh of her own. “And I really enjoy the animals.”

Each year the farm produces 100 head of beef, 70 lambs, 30 deer and a handful of goats for their plant, along with 10,000 free-range chickens, 1,300 turkeys, around 2,000 ducks. But they don’t just process their own meat. “The business has grown so much that we’re just not focusing on our own farm, we have a lot of neighbouring farms that grow a lot of our product on their farms and we purchase it and slaughter it and so it creates a value chain in the community and it allows us to bring more local farm products to the city,” Oulton says. “We sell a lot of exotic meats to restaurants, and to consumers as well.”

The farm has been direct marketing a variety of meats: Your standard beef, lamb and poultry and a diverse mix of niche products like goat, emu, wild boar, elk and yak. You find it at Pete’s Frootique and at farmers’ markets under the Martock Glen Farm brand, and see reference to Oulton’s farm on menus at the Stubborn Goat, Morris East, Bistro Le Coq and dozens of other restaurants from Halifax to New Minas to Bridgewater.

“It’s growing for us. We’re trying to grow different things all the time. Even though we try to stay as local as possible we want to stay interesting and have a variety, so we’ve actually brought in things like camel and kangaroo which are not feasible to grow here,” Oulton says. They buy that type of exotic meat from a broker in Montreal.

“We carry a couple of little things like that—things that keep the conversation going—as long as it’s interesting and it’s good meat. It’s a very marginal part of our business, but, on the other hand, it’s also a growing part.” The Meat Store also makes an effort to provide specialty products, like burnt goat and Halal meats, to growing communities. ”We are able to accommodate different types of butchering and meat upon request for our customers and their cultures,” says Nicole. “We have been able to adapt to these requests and needs of our customers because we are a small scale abattoir.”

Growth interests Oulton, but sustainability is what is most important. “We’re farmers at heart and we farm all we can. We’re kind of maxed out on our land, but we’re farming what we can on that land,” he says. “But of course the marketing business—the slaughterhouse and that part of our business—has definitely grown and requires more and more time all the time. Just to manage that as well as try to keep all of our customers happy requires more and more time and takes us away from the farm but because everything is situated on the farm it makes it a little easier.”

The Meat Store is actually just a hop and a skip from the barn, in a lot just past a shed where the sun-baked skulls of deer and sheep throw their empty gazes out over the pile of stacked wood. You can’t avoid the gruesome nature of the business: Animals are killed here.

The air inside the shop itself is tinged with a heady smell like summer rain hitting rusty garden tools. Warm, metallic, earthy. But even with the pinky-red gore splayed across the butchers’ aprons, and the sanguine curves of animal carcasses hanging from industrial hooks, the atmosphere is cheery. The small details are macabre, but the big picture is pleasant.

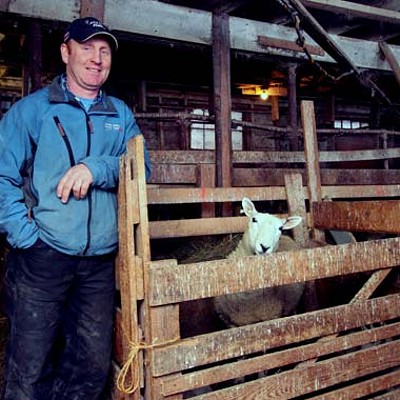

The thing is, you can see the care and regard for the animals in Oulton’s treatment of them as he wanders through the barn checking the stalls, in the interest the butchers take in their work in the shop. There is dignity in the lives of the animals at Oulton’s Farm, an obvious respect for the creatures on whose literal backs the family makes their living.

Right now the barn is a cozy refuge from the snow for the various animals. A heat lamp keeps two pet kangaroos extra warm and happy; when Oulton opens the door they hop over to greet him. An emu pokes its head through an opening in its door in a moment of lazy curiosity, while a zebu across the aisle stands calmly next to her tawny calf. At the back of the barn, just past a couple of wild boar and a small herd of goats, sunlight streams through the slats, giving a flock of sheep with a handful of knobby-kneed lambs hazy, wooly halos. Elk and yak wander in the fields out back. It’s a series of serene tableaus that belie how busy it’s about to get busy for the Oultons.

“From the first of April through Christmas time—that’s when we grow the bulk of our products. All of our poultry is grown in that period. So we go from eight-hour days to 12- or 14-hour days, seven days a week,” Oulton says. “All our calves are being born right now, our lambs are being born. In May the deer are being born. Starting this week we hatch several hundred ducks and chickens every week. This is the start of the cycle of life for the Meat Store.”