Through 1868 and 1869, Stephen Martin Saxby, a lieutenant in the English navy, repeatedly warned that astronomical conditions would create exceptionally high tides on the upper reaches of the Bay of Fundy on October 5, 1869. “There will be time for the repair of unsafe sea walls,” wrote Saxby, but that warning was largely ignored.

The high tides Saxby predicted for October 5, 1869 were joined by a hurricane, retroactively called the Saxby Gale, that swept just to the west of the Bay of Fundy, bringing an additional storm surge of two metres up the bay. The extensive network of dykes was overtopped, and hundreds of people lost their lives in the Amherst, Nova Scotia and Sackville, New Brunswick region.

Exceptional tides are now easily predicted but, like Saxby, a modern-day forecaster’s warnings of dyke-topping floods in the upper Bay of Fundy seem to be just as ignored. At risk are Nova Scotia’s transportation links to the rest of the continent, valued at $50 million a day.

In 2009, Tim Webster, a research scientist with the Applied Geomatics Research Group at Nova Scotia Community College's site in Middleton, was contracted by the Nova Scotia Department of Environment to study flooding potential across the Chignecto Isthmus that connects Nova Scotia to New Brunswick. His report was published last year, but has been largely ignored by the media.

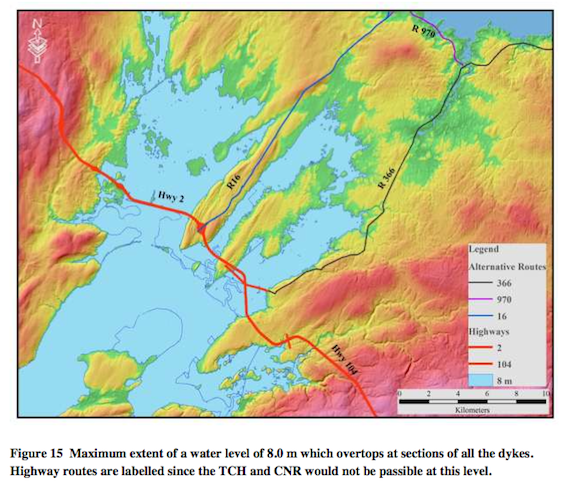

Using new elevation measurements of the isthmus and predictions for sea level rise, land subsidence (Nova Scotia is sinking at a rate of about 15 centimetres per century), high tides and assumptions of storms bringing two-metre surges, Webster was able to map out various flood scenarios. A simple eight-metre tidal/surge event equal to that of the Saxby Gale would overtop the dykes and put about four kilmetres of the Trans Canada Highway under water, as well as make the CN tracks impassable.

“It’s really hard to figure out and predict how long it would take us to get rid of that water,” says Webster in a phone interview. “All of that low-lying area is totally saturated with a bunch of wetlands. You know, the ducks love it. There’s nowhere for that water to go in terms of into the ground, so we’d have to depend on getting rid of it again at low tide, through the dyke somehow.” Even if we were prepared for the break in transportation, it could take many days to repair they system, says Webster. If we’re not prepared, it could take weeks or months.

And, notes Webster, while his modelling is based on a two-metre storm surge, last year’s Hurricane Sandy brought a four-metre surge to New Jersey. “I don’t think it’s a big leap for us to think that with climate change the storms hitting New Jersey and the Carolinas now are going to be able to maintain their strength farther to the north.”

Webster says that a combined 12-metre rise in water from high tides, sea level rise and storm surges could make Nova Scotia an island. That sounds like a lot, says Webster, “but take the IPCC new projections for sea level rise for the century, two metres, then you add some storm surges...and you have some problems.” In his report, Webster notes that the IPCC’s “worst case” sea-level rise models have already been exceeded, and that NASA climate scientist James Hansen has be warning of a five-metre rise in sea levels by 2100.

In the short term, Webster has real worries about storms during high tides. The highest high tide in the next few years comes on October 28, 2015, still in hurricane season.

“If we ever get a prediction of a hurricane or another big storm occurring when we have a new moon, like Hurricane Sandy—either a full moon or a new moon, when the tides are higher than usual," says Webster. "And it happens to be tracking up the Bay of Fundy, especially if the eye goes to the left of the bay, that means the winds are pushing seas up the bay—if I was planning a trip to New Brunswick by car, I’d be looking at alternatives.”

Webster makes three recommendations to prepare for flooding: We could "retreat"—move the highway to higher ground—"but that's a huge investment." Or, we could "defend"—put more money into maintaining and raising the existing dykes. In the wake of last fall's flooding near Truro, the province has added about $2 million annually to dyke maintenance, but that's probably not enough to prepare for really big surges. Lastly, says Webster, "we could do nothing, and hope we don't get hit."

See Webster's full report here.