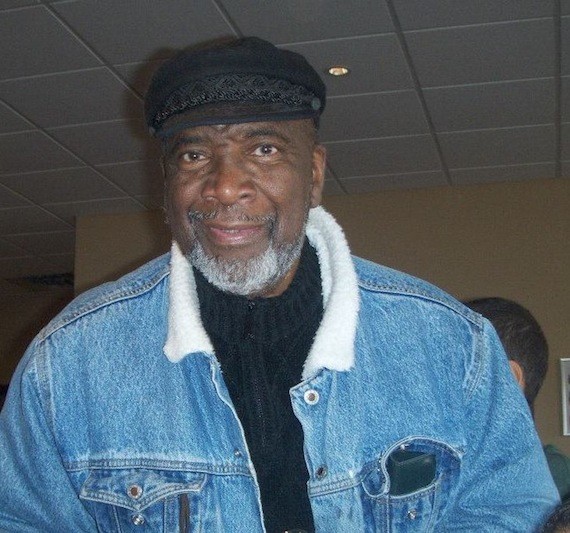

Editor's note: Burnley Allan "Rocky" Jones died Monday night. The following piece was written by Coast intern Rana Encol after Jones gave perhaps his last media interview, earlier this year. It is one of several profiles of prominent Haligonians we've collected as part The Coast's 20th anniversary year, and which will run over coming months.

Rocky Jones: “The kids will react”

In 1968, Stokely Carmichael, a political mover in the US and Africa, met up with Rocky Jones at the Black Writer's Congress in Montreal. Jones invited Carmichael up to Nova Scotia to go fishing, but when Carmichael arrived, the FBI, the CIA and several police cars swarmed outside the airport like flies.

“We can't organize revolution around a car accident,” joked Carmichael to Jones, cops in hot pursuit. The pair had only planned to go fishing, a chance to decompress amidst the freedom rides, race riots and other tumultuous events of the 1960s. At the time, Carmichael was fighting for civil rights and Jones was actively organizing as a student and activist in the peace and disarmament movements in both the US and Canada. Fast forward to the 1995 G7 conference held in Halifax, and once more the FBI and CIA settled on town to patrol the streets and spy on its citizens. Sewer covers were welded down and police cars wouldn’t stop to let pedestrians by. Despite the oppressive presence of the policing apparatus, singers, dancers and activists flock to the Halifax Common for the Alternative People's Summit. Jones co-chaired the event.If you told Rocky Jones that he'd lead a people's summit when he was growing up in the marsh in Truro, he'd say you were crazy. There were 10 kids in his family. His mother scrubbed floors before she became a teacher. His father worked in a boiler room. They had nails sticking out of the walls which turned white in the winter from the frost.

Freshly called to the bar in 1993, Jones ended up defending a black kid from Mulgrave Park against a white cop who claimed he was assaulted by the kid while making an arrest. The optics of the case were divided along racial lines: On one hand, there was a black court reporter, the only black judge in Nova Scotia at the time and a black lawyer (Jones) representing the accused. On the other hand, a white cop and a white attorney. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada to determine what Jones calls the “ruler stick” or apprehension of bias in the judgment of a case: How much should context inform a judges' decision? In this case, the black judge had ruled in favour of the accused, citing that young officers tend to overreact when dealing with non-whites. Rocky Jones objected: “I'm not non-white anything. That is a pejorative term.” The police union and prosecution appealed the judge's decision by claiming racial bias against the police. “I had just graduated law school and here I was in a crash course in courts and legal concepts, going against the best lawyers in the province before the top judges and legal minds in the country,” recalls Jones. But that was only the beginning of his career. Then there was the defamation case, when three young black girls were brutalized by a cop looking for a stolen $10. Representing the girls, Jones and then-lawyer, now-judge Anne Derrick held a press conference where they claimed their clients were searched without their parents’ knowledge because they were poor and black. The police officer, inferring that she’d been called a racist, sued for defamation and won a huge award against the lawyers. But that ruling was thrown out on appeal, the judges making clear in their decision that Jones and Derrick weren’t just within their rights to say what they said, but actually had a duty to speak out on behalf of the girls. The biggest problem facing the black community today, says Jones, is a lack of unity. Developers are slowly encroaching on the historical land base of Nova Scotian blacks and their political power is diminishing, partly as a result of internal divisions within the communities. Black students rank on the bottom of the academic ladder—people point to individual successes, but the masses are poorer than they were 20 years ago, he opines. Communities once held together by church and social agencies are disintegrating because of poverty and unemployment. What remains are unmoored individuals, often enticed by cars and other status possessions “held out as carrots.” “But people have survived this long as a collective,” says Jones. “We have survived because of our tightly-knit communities which are being dismantled. We cannot survive as individuals: divided we fall.” Racism. Sexism. Poverty. These are the root causes of the internal violence. “We're not the big employers in this province,” he says. “We cannot open doors for our own young people.” While many struggle to carve out their own dignified paths in life, many others choose antisocial behaviour instead. “The kids will react if it’s a racist society,” he says. And that's beyond a reasonable doubt.XXX

For more background, here's Stephen Kimber's profile of Rocky.

And this National Film Board documentary from 1967, "Encounter at Kwacha House," is particularly interesting:

Encounter at Kwacha House - Halifax by Rex Tasker, National Film Board of Canada

And here's Rocky himself, from last year, giving a TedX talk:

And finally, from yesterday, here's El Jones discussing Rocky.