According to first quarter statistics released yesterday by Halifax police, violent crime is down in 2016, compared to the same period last year. Doesn't feel like a very peaceful year, though, does it?

Despite a recent string of gun-related homicides that shook the city, violent crime has generally been on a downward trend for the last several years, and police are seeing fewer guns on the streets. But according to Halifax Regional Police, there remains a sizeable demand for firearms amongst those involved in criminal activity. So how are crime guns getting into the city?

The short answer is they’re stolen from legal gun owners or bought through straw purchases. The long answer is, well...long.

Detective sergeant Darrell Gaudet, head of HRP’s Special Enforcement Section, says the majority of guns Halifax police confiscate originate from domestic break and enters. That’s part of the reason HRP are working on education programs to make sure legal gun owners keep their firearms secured.

Most of those guns will be non-restricted rifles and shotguns. Police also confiscate handguns, modified rifles (with shortened barrels) and increasingly, realistic air-soft BB guns.

By their nature, though, there’s a lot we don’t know about illegal guns. It’s hard to gauge the impact of straw purchases (legal gun owners buying firearms to sell after-the-fact) on the market, for instance.

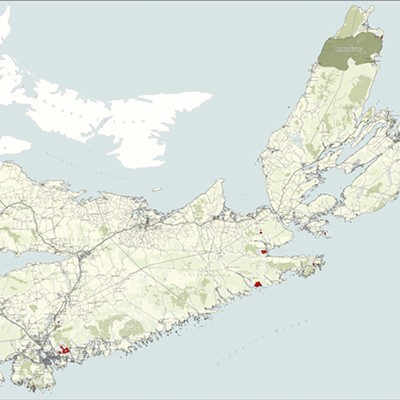

There are also the guns that are being brought into Nova Scotia after being stolen elsewhere. That happens, Gaudet says. There’s also the black market of illegal guns that get smuggled into the country (largely from the United States).

Border services seize hundreds of guns coming into Canada each year—mostly from trigger-happy Americans who “forget” to declare. A Toronto Star report found 2,641 guns seized at the border between 2005 and 2009, most of which were those legally-owned “mom and pop” guns. The Star also found border services is confiscating half the number of guns they did a decade ago. Meanwhile, upwards of 70 percent of guns recovered at Toronto crime scenes come from the United States.

A 2014 story by the

But Nova Scotia doesn’t share a border with Michigan. Unless the CAT ferry really takes off, a similar scheme won’t work as easily here. Likely any illegal guns being brought into Nova Scotia are coming from other provinces, even if they originate in America.

Except, that doesn't appear to be happening either.

The Vancouver Sun recently found that more and more of British Columbia’s criminals are buying local. Area RCMP said 61 percent of crime guns are either stolen from legal gun owners or bought domestically through straw purchases. National Weapons Enforcement Support Team inspector Chris McBryan tells the paper that the shift to locally-sourced crime guns is happening right across Canada.

“The idea that most crime guns are domestically sourced now is consistent.”

All of which is to say that without a comprehensive audit conducted by the criminal underworld, it’s a little hard to pinpoint with any certainty the source of every crime gun in this city. It’s unlikely the police are lying about the majority of their confiscated crime guns coming from domestic break and enters, but a lot remains shrouded by untraceable weapons and the impact of “grey market” straw purchases.

“I wish I had those stats,” says Gaudet. “That would be great because then we’d know who’s selling illegal guns.”

We do, kind of. Or at least, we know who used to be selling them.

At 4:30am on January 15, 2009, about 100 police officers assembled at RCMP headquarters for Operation Intrude’s “take-down” day. Launched in 2007, Intrude was a massive police investigation into the “Spryfield Mob” (or SMOB) for violent assaults, attempted murder, drug dealing and gun trafficking.

That morning, officers took part in a series of orchestrated raids and arrests across the municipality. Kyle Cater, then in Grade 12, was arrested during gym class at J.L. Isley High School after police found guns (including a Cooey 84 shotgun, a Lakefield Mark II rifle and an AA Arms Model AP 9mm handgun) at his father’s house. Cater was one of Intrude’s main targets and a major source for guns in the city.

He was “valued as a potential supplier by individuals looking for working guns that offered his confederates the opportunity to employ deadly force,” trial judge Anne Derrick noted in her 2012 decision.

The evidence against Cater gives a small window into how he was getting his guns into Halifax. During one wire-tapped phone call in 2008, Cater tells a friend looking for a “clip” not to worry because “I got people that live out Edmonton and they send them down like it’s nothing.”

It’s possible, of course, that Cater might have been embellishing the ease with which he could acquire new merchandise. A subsequent incident, caught on tape by police, showed the panic when a handgun briefly went missing from Cater’s dad’s house. Here’s ex-Herald journalist Dan Arsenault, reporting on the incident as it was recounted at trial a few years later.

“They discussed who was at the house that night and decided to round them up. Kyle Cater was later told that two of the three people who were at the house were brought back. They had already been ‘patted down’ and didn’t have the gun.“During the call, Kyle Cater was agitated and repeatedly asked how it could have gone missing because it was supposed to be kept hidden. He asked if it was misplaced.

“Minutes later, the gun was found.

“In a subsequent call, Cater’s stepmother tells him that the two boys they rounded up and patted down ‘were scared as fuck’ and ‘had things in their face.’

“‘Thing’ is a code word for a gun, a police expert told the court, meaning the two boys had had weapons pointed in their faces because of the mix-up.”

“In 2011 metropolitan Halifax had the second highest rate of homicide among CMAs in Canada and in 2012 the fourth highest. HRM has the highest rate of firearm-caused homicides in Canada. As a well-known and knowledgeable public housing resident/leader observed, in describing the circumstances of violence as so different from previous decades, ‘the boys got guns now.’”

tweet this

—Don Clairmont’s 2014 update on HRM’s roundtable on violence

Arsenault reports that a shotgun on the street can be worth $400 to $800. A hunting rifle would be worth just $200, and a handgun could go for between $4,500 and $5,000.

The price of an illegal gun depends on who you are “in the pecking chain,” says Gaudet. Given that a handgun is potentially 10 times the cost of a shotgun, or 20 times the price of a rifle, simple economics would suggest it's not a leap to assume there are more long guns than pistols on the street.

Hunting rifles actually work quite well if you’re looking for a concealable weapon that packs equal parts intimidation and stopping power, says Gaudet. A sawed-off rifle can easily be slipped down the leg of your pants or held in a jacket sleeve. Plus, there are a lot of hunting rifles in Nova Scotia.

So we're pretty much right back to where we started. Halifax police say the guns they confiscate are mostly non-restricted and largely stolen from local, legal owners.

But all of that data is just for the firearms police can trace back to a point of origin. Filing a serial number off a gun, which police often see, will obviously makes it harder to track. Dianne Woodworth, spokesperson for HRP, also notes that non-restricted firearms (such as hunting rifles) no longer need to be registered and therefore “there is generally no way to trace the origin” of those guns.

In which case, your guess is as good as mine.