Quentrel Provo knows a lot of people along Lake Major Road in North Preston. All those people, friends and family, asked him a lot of questions one day after the police pulled him over for speeding. He was embarrassed, he says, especially because he was working as his church’s youth pastor.

“I was actually really hurt by it because I felt like I never did anything wrong,” says Provo. “I’m just driving a sports car and it’s almost like you’re not supposed to have that car.”

Provo, 28, is studying to be a paralegal, already having made a mark in the community as an anti-violence activist. Often his volunteer work has involved police, not an easy task for him, he says. He’s had a tense history of police interactions, despite having no criminal record at all.

That afternoon, Provo drove his Mustang from East Preston onto Highway 7 and up Lake Major Road. As he left East Preston, Provo says he saw a police car do a U-turn and follow him. Once they hit Lake Major, on came the lights.

“I pulled over thinking that he had a call or something. He pulled behind me and asked me to get out of the car, said I was speeding,” says Provo. “I was like, ‘How am I speeding? You were behind me the whole time.’”

He says he ended up avoiding a ticket, and arranged a meeting with the local RCMP detachment. He wanted to discuss how he felt the officer had profiled him, a black man driving a nice car.

“He must have thought, stereotyping, ‘From North Preston, what is he doing? Is he selling drugs? Is he out there pimping?’”

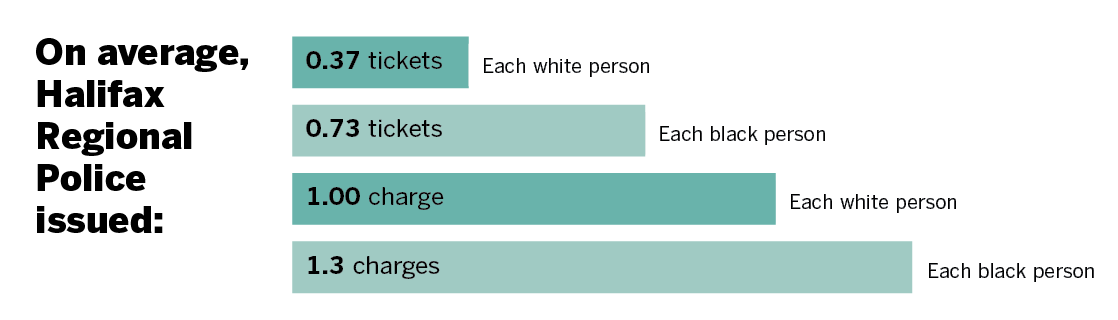

Provo had probable cause to suspect racial profiling: Proportionately, black people are ticketed twice as often as white people, according to data we obtained through freedom of information legislation.

The Coast received Halifax Regional Police numbers for summary offence tickets and charges from October 2010 to October 2014, broken down by race and gender. Police warn the numbers may be slightly inaccurate, due to the ticket recording system going digital in recent years. Race and gender are selected by police in the case of tickets, and are self-reported for charges. These numbers also do not include RCMP data, which would cover much of the municipality.

Summary offences are less serious crimes dealt with in a guilty or not guilty plea. That’s anything from disturbing the peace to speeding.

On average, white individuals receive half as many tickets as black Haligonians. Using Statistics Canada population data with the ticket numbers shows that the average black person in Halifax received 0.73 tickets and 1.3 charges over the four-year span. White people averaged half the tickets—0.37—and a single charge per person. Halifax’s population is 3.6 percent black, roughly 90 percent white.

Provo is the founder of Stop the Violence, an organization dedicated to the memory of his cousin, Kaylin Diggs. In 2012, Diggs was killed on Argyle Street after trying to help out a friend being assaulted by a group of men. “With tragedies, you're never at peace,” says Provo. “You just try to go on with life. They say it gets better with time. It really doesn't, but you learn how to be stronger. You learn how to cope.”

Provo works with youth, visiting schools to talk to students about avoiding violence. For two years, he’s run a well-attended march against violence to bring the community together.

“There’s more good coming out of us in North Preston and East Preston than there is bad,” says Provo, “but the bad is what gets highlighted. Me as a young man and a few other young men that I know are just trying to be the positive role model to set the example.”

In the same way, one bad interaction with police can make it hard for a community to trust the whole force.

A couple years ago, Provo says he was assaulted at a party, the man jumping him from behind.

“Bang, bang, bang, just started hitting me from behind, punching me in the face.”

He then fell, hitting a bicycle rack. Provo says his face is scarred from the bruising. Despite his requests, Provo says police didn’t press charges.

“I got through it, and that's why I'm so passionate about Stop the Violence. That's the thing a lot of people don't understand. I could have lost my life that night.”

Constable Shaun Carvery works as HRP’s diversity equity coordinator and oversees related training. It was the RCMP who dealt with both of Provo’s situations, but avoiding racial profiling is why Carvery’s position exists.

“The complaint comes up a lot. People feel that they’re being profiled,” says Carvery. “Just looking for that explanation of, ‘Why am I being stopped?’ In reality, if you don’t have a good reason for stopping somebody, then we’re acting upon our own biases.”

That training is mandatory, says Carvery. From Halifax’s north end, Carvery joined the police force in part because as a black man he didn’t see himself reflected.

“You're going back into your own communities and people say, ‘I know you. You look like me. We're from the same place’,” says Carvery, now a 14-year veteran officer.

Provo says he’s working towards the same goal, but it’s a tough gig. That’s especially true, he says, when he sees police put their hands on their holsters when talking to tipsy people downtown, or when he hears of an officer charged with drunk driving.

“To this day, that’s why I stay close to the police, but in a certain way, where I’m not close with them. I respect them and what they do,” says Provo, “but just to be offering help to them and trying to partner with them, it’s hard. It really is hard.”