It's August 2006, and Toronto producer Laszlo Barna is sitting on a couch in the stately foyer of Shirreff Hall at Dalhousie University, leaning forward as sunlight dapples through the windows behind him. He's keeping his voice down in consideration of his film crew shooting a scene one room over, the spaghetti strands of electrical cable running across the hall through a propped-open door a dead giveaway. Barna's English is accented from his Hungarian upbringing, and his tone is calm but intense.

He repeatedly uses the honourific "The General." For example, he says, "We spent a long time with the General, we tried to follow the through-line in the story as close as we could."

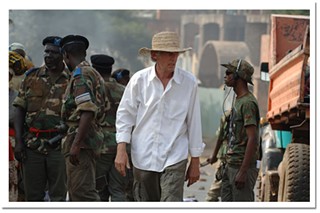

It is a good indicator of the kind of respect the filmmakers have for their story's inspiration. The General is, of course, Roméo Dallaire, and the film being shot here in Halifax is the dramatization of Shake Hands with the Devil, Dallaire's memoir of having been a UN force commander in Rwanda in 1994 during the period when Hutu extremists slaughtered thousands of minority Tutsis. The film is produced by Barna and his company Barna-Alper Productions, and Michael Donovan, with Halifax Film. Donovan also adapted the script from Dallaire's book.

These days most people have heard about what happened in Rwanda 13 years ago, and though the UN and the world community were widely criticized for having ignored the slaughter, Dallaire's book, as well as Peter Raymont's 2004 documentary, Shake Hands With The Devil: The Journey of Roméo Dallaire has gone a long way to clearing the General's name, in this country, anyway. There have been a number of films that have depicted, from various perspectives, what happened there, most prominently Hotel Rwanda starring Don Cheadle, who earned an Academy Award nomination. But the character in that film meant to represent Dallaire, played by Nick Nolte, was shown in a less-than-flattering light.

"Peacekeepers in general in Rwanda were depicted badly," says Barna. "The General in particular was depicted badly...it was simply cruel, untruthful and unacceptable from the Canadian point of view that he would be maligned. The General goes to great lengths...he says, "Do not portray me as a hero.' We don't. We portray him as a witness, a man caught in these circumstances."

The story that is being told here, from the filmmakers' perspective, is more complete than has been told in the other movies about the subject. "I don't want to say we tell the true story because there were elements of truth in those other films," says Barna. "But this film takes a particular look at the role of the UN Security Council, a look at those political events that were unfolding, the French collusion in the genocide. Kofi Annan is in this film. Mistakes were made. People misread this. We want to be forward looking and say we do not want this to happen again."

When it's Michael Donovan's turn to sit on the couch, also keeping his voice down, he is equally as passionate about having shepherded this project to its realization. He says he's "horrified" to admit that it was a story in the newspaper about Dallaire that first made him aware of the Rwandan genocide, as there'd been so little press coverage while it was happening. He optioned the book before its publication, and negotiated with Dallaire on how the film would be made.

"One of the conditions he placed on it was that it be shot in Africa," says Donovan. "Another condition was that the lead be French-Canadian. Though I conceded on the Africa thing I didn't want to on the French-Canadian thing. I didn't want to limit it...the ideal person might be Dutch or American or British. And there's the whole issue of a name in a movie."

The irony, from Donovan's perspective, is that the ideal candidate for the role was French-Canadian: Roy Dupuis. "He was on the back of our mind for a couple of years, but so were a number of Hollywood types. But once Roger,"—Spottiswoode—"our director, met Roy it was clear. He had no doubts. And the more we thought about it the more logical it became."

The door to the room where a scene is being shot opens periodically as crew go in and out, revealing Dupuis standing in a well-appointed meeting space, in full make-up. The grey in his hair and moustache goes a long way to aging him toward his late 40s, which Dallaire would have been in the mid-'90s. Shirreff Hall is standing in for an Ottawa therapist's office: the scenes deal with Dallaire's time after Rwanda, his struggling with a well-publicized case of post-traumatic stress syndrome.

"We agonized about that a great deal, about its relevance," says Barna. "We came down on the other side, that we had to tell a complete story. It's a character-driven film. It had a tremendous impact on him and it's common knowledge that he was suicidal."

Shake Hands With The Devil took years from inspiration to shooting, a 42-day schedule, with 38 in Kigali, making use of many of the sites where the actual events took place 12 years earlier.

"It was inconceivable to go to Rwanda at the beginning," says Donovan. "We thought of South Africa. But slowly, we saw that other films had been shot in Rwanda. And what we wanted was a completely authentic film. Everything vigorously real."

The concern was, besides the fact that Rwanda has no film industry, the populace had so recently participated in this incredible trauma that was going to be reimagined before the eyes of locals, many of whom would be playing roles in the film. The situation required unusual precautions to be taken while on set in Kigali.

"Twenty-four-seven we had a psychologist," says Barna. "From time to time, when were doing recreations with dead bodies or machetes it was very upsetting. People were crying, sometimes people freaked out. The psychologist talked to people before and handled anything that came up on set. And Rwanda is very densely populated, so any time we'd set up, boom, there'd be a lot of people. We had to be really careful not to create psychosis."

Barna says that the Canadian crew, a third of whom were from Halifax, were overwhelmed by being in Africa, by the sudden understanding of people who are living with so little, and at the same time, a country that is rebuilding. "We felt we were a part of that, we were spending the money in the right place, part of the process of setting the history right."

The main character of the film, says Donovan, is the country, the place. He's only a few days off the plane from having joined the crew in Kigali and it's clear as he speaks that he was transformed by the place. "You have to be there to understand this," he says, in deliberate, measured tones, "but it's just that it is the most beautiful place in the world.

"Full stop, period. In other words, it is paradise, it is heaven on earth. More than just physically, it is mystically beautiful. It's hard to say why, but you have a sense that this is where life began. So, heaven on earth turned overnight into hell on earth. That has deeply affected this story. We could not capture that in a location outside of Johannesburg."

The director of Shake Hands with the Devil, the Canadian-born Roger Spottiswoode, has worked in the British film industry and in Hollywood for many years and was chosen for his diverse body of work, everything from the Nick Nolte political thriller Under Fire (1983) to the AIDS drama And The Band Played On (1993), even a Bond movie, Tomorrow Never Dies (1997).

"I'd be dishonest to say that it was the James Bond film that attracted me," says Barna, laughing. "That would have meant certain bankruptcy. But I was really interested in getting someone who'd done a body of work that was edgy and focused on a certain complicated storytelling...and still root it in character. And he was fearless in telling the story as it was."

"He is delivering a truly great movie," says Donovan. "Very possibly the movie of his career, definitely the movie of my career. I personally think, that on my death bed, this will be the one that I remember."

He adds, "But nobody may see it."

He's a realist when it comes to making a film on a difficult subject. And though Barna praises the investors who helped make the film a reality—they include Corus, Astral Media, Telefilm, The Harold Greenberg Fund and the CBC—Donovan is a bit more blunt about the struggles to get Shake Hands With The Devil made.

He describes it as "the most difficult film for me by far in 27 years, to finance and to organize. Because who actually wants to see a movie about a man who goes off into a mission to Africa—and who cares about Africa—that fails miserably and a million people die? I've had over 1,000 conversations with various funders around the world, and almost every one of them saying, "Who wants to see a movie like this? It's such a downer. And besides, hasn't Rwanda been done?' And they say one other thing: "Between you and me, no one wants to see Africans on screen. Lets get real.'"

But they were wrong, as the critical and modest commercial success of a films such as The Last King of Scotland, The Constant Gardener and Blood Diamond indicate.

Donovan has a rule with his projects: When he encounters too many obstacles, at a certain point he acknowledges that the fates are telling him to stop.

"So you just walk away...but, for some reason, on this one we just kept persevering, me and Laszlo," he says. "We just kept on going."

Shake Hands with the Devil, September 13 at the Oxford, Oxford at Quinpool, 6:30pm and Park Lane, 7pm and 7:05pm, $16, 422-6965, atlanticfilm.com

Carsten Knox spent three years of his childhood in Africa. Of movies set there, he can recommend The Constant Gardener but thought DiCaprio's Rhodesian accent in Blood Diamond was ridiculous.