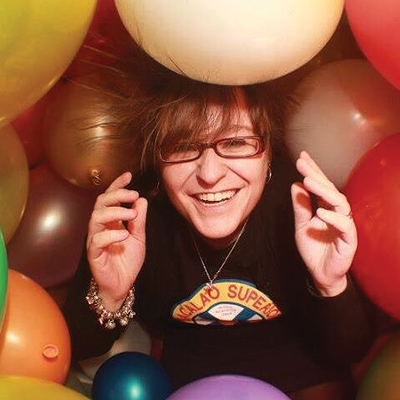

Nico the cat judders before springing atop a cafe-style table as comedian/teacher/writer Sherry Lee Hunter, set to swear off the lung rocket habit, fires one up. She inhales, then beats a beeline for an open side window above the sink counter in her compact kitchen. Trim, she moves around the room with the easy grace of a seasoned performer.

Perched astride the counter’s edge, she exhales a blue stream of smoke. From two walls, the broad grin of a pleasant-faced, middle-aged man beams from several pictures. Not the Dalai Lama, but the “Salvador Dali of mime,” Tony Montanaro.

The late Montanaro, a world-renowned teacher, performer and authority on mime, was for Hunter and fellow rascalians, a mentor, nurturer and friend. Hunter—who performs this weekend in On the Waterfront Festival’s Buffoon Buffet—says that meeting him was the beginning of her serious training. “Montanaro was the master, a man surrounded by comedy people from all over—you name it. He taught disciplines from slapstick to subtle character work to broad ensemble work. No better training to be funny.

“There’s a bunch of broad physical slapstick humour you can learn,” she continues, feigning a trip, a stumble into a wall, first driving a foot into the baseboard for the “THUMP!”—before bouncing back, clutching her “bruised” nose. “Like learning dance steps. But as Montanaro would always say, ‘Intent and premise is the most important thing. Who wants to see an illusion for its own sake?’ I want to see a character. Who walks into a room,” Hunter walks her open palms along an invisible wall, “and feels a wall. Right? It’s got to be a character that’s feeling for something.”

Looking vertigo-spooked, Hunter ascends an imaginary ladder. “Or climbing, going somewhere. Same with broad humour. Don’t just have a bowl of something fall on my head. It’s who the character is and why the bowl is falling.”

Hunter first saw the light while in her mid-teens: “When I was 15, I went to Toronto by myself to visit someone. Fresh from Dartmouth, I saw somebody masturbating on Yonge Street. A man dressed as a woman. Different things. Then I saw this mime on the street. Not what I call ‘shmimes’—those white-faced people that terrorize people in shopping malls. Don’t like those. But this guy was doing the most brilliant pantomimes and it blew my mind. I thought, ‘I have to learn how to do this!’ I’d never seen that before. The illusion. I just loved it. To see him imitate people and be so precise. That really opened my eyes.

As a kid, Hunter favoured TV’s exceptional comedic character actress Carol Burnett over Lucille Ball. But her real comedic love—also a particular fave of her mother’s—is the comic chameleon Peter Sellers; specifically, his brand of broadly subtle humour. “I liked physical comedy with brains,” Hunter makes clear. “The Three Stooges? No. They just gave my brother more instruments of torture. He tried all their moves on me. Oh yeah.”

Family humour swung between squishy soft to dryly dark.

“My father —corny. He’d tell a knock-knock joke and laugh for half an hour. At his own joke! He loved Red Skelton, that kind of soft, sweet humour. My mother —more dry. She’d say things like, ‘Do you kids want some hotdogs?’ We’d reply, ‘Yeah, mommy, yeah.’ And she’d say, ‘Seen the dog lately?’ And I’d look for my adoption papers. I couldn’t possibly have come from this family.”

A Navy brat knows about moving around. A lot. Hunter’s family relocated from Manitoba (her birthplace) to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Dislocation and the spillover effects of alcoholism, then so rampant in the armed forces, proved at times stressful—a sensitive issue with Hunter. “I wanted to be involved with comedy since I was little, “she says. “A lot of comics came from hard times and we had some hard times. That’s probably why I was drawn to comedy—although that’s psychoanalyzing it now. As a kid, I just liked it. I loved to make people laugh.”

And make people laugh she did, achieving national and international acclaim on stage and TV specials with the seminal comedy group Jest In Time. Along with Mary Ellen MacLean, Shelley Wallace and Christian Murray, Jest In Time dazzled audiences and critics alike for 20 years before recently disbanding. And, always there, as principal mentor to help shape their ingenuity, Tony Montanaro.

It’s a fact that must be faced by every ambitious comedian. Just being gifted and brilliantly funny is not enough to cut it, given current neo-conservative corporate media control. “It’s going to be so interesting to see what happens with comedy over the next four years with the right in power,” Hunter muses. “Montanaro was always saying he thought there’s going to be a resurgence in the artform of live physical theatre.”

So what’s a funny girl to do to showcase her stuff?

Hunter pauses to think. “Standup is brutal. Even harder for women. Much harder. So I haven’t gone that route. Jest In Time is interesting because we had three women and our token male, as we always teased Christian. So many comedy groups are six guys and one woman. They have to have that little bit of feminine. The creation of Seinfeld—they had George; they had Kramer. But the creators realized they had to have a girl. It just wasn’t going to work. Why is that? Because men, just by themselves, it isn’t enough. The thing with Jest In Time is we played male and female. All the time.” A smoky chuckle interrupts the flow. “Christian played female, which he hated.”

She feels that theatre is the strongest forum for women who want their voices heard in comedy. Theatre shows like Lily Tomlin in The Search for Intelligent Life in the Universe.

“Jane Wagner wrote that. It worked brilliantly. We need to see women being funny. We have a sense of humour that’s broader because women have a lot more on their plates; a wider spectrum to work from and to present as funny. That’s why Ab Fab worked. Women watch TV as much as men. We need to be able to see ourselves on television.”

Nico the cat drops to the floor and skitter-skatters off to explore the adjacent living room.

“I think I’m going to stick with theatre,” Hunter says. “Networks can’t control—they can’t own live theatre. It gives me faith. The play I’m writing, called After The End, is all about isolation and aloneness and it’s going to be a comedy. And I’m playing...”

Hunter transforms into a funny character.

“It’s going to be neat. It’ll be an idea of what I can do in live theatre I could never do on television. I don’t think there’s a better high than performing on stage when you know it’s working. And people are laughing.”

Did Montanaro’s grin just get bigger?