If they’re not careful, the Liberals’ election promise to end Canada’s discriminatory gay blood ban could end up slipping through the bureaucratic cracks.

The newly-elected Liberal government promised to end the restrictions Canadian Blood Services has in place preventing the donation of blood by men who have been sexually active with other men, but ending the blood ban could take years of detangling red tape.

Until 2013, Canadian Blood Services outright barred men who have sex with men (MSM) from donating blood. The policies were revised two years ago to allow donations from men who had refrained from sex for the previous five years. It was a glimmer of progress, at least, but still based on what LGBTQ advocates call an outdated, homophobic viewpoint.

“Any deferral period is discriminatory,” says Rebecca Rose, board chair of the Nova Scotia Rainbow Action project. “It needs to be a behaviour-based model...there is nothing intrinsically less safe about queer sex, about gay sex.”

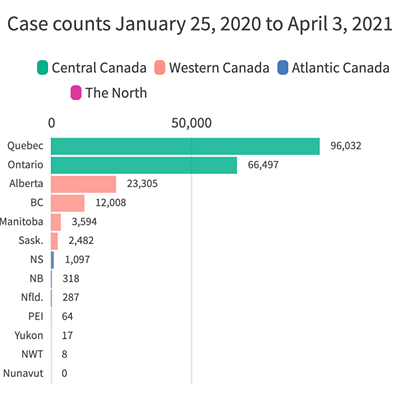

Statistically, MSM account for the highest proportion of HIV cases in Canada—roughly 49 percent nationally and in Nova Scotia. This means Canadian Blood Services classifies men having sex with men as a high-risk activity.

The Liberal Party, under new prime minister Justin Trudeau, has said it will bring down the ban, stating this ban ignores scientific evidence and “must end.”

“A Liberal government will work with Health Canada, CBS and HM-QC to end this stigmatizing donor-screening policy and adopt one that is non-discriminatory and based on science,” a Liberal party statement reads.

But LGBTQ advocates say actions will speak louder than words. “As of right now, it’s a campaign promise,” says Rose. “We need to see them re-commit to it post-election. We need to see a timeline and action.”

Mindy Goldman, medical director of donor and clinical services at Canadian Blood Services, says the organization looks forward to having an “open dialogue” with the Trudeau government about any policy changes. Canadian Blood Services doesn’t have total control over its own operations. Requests for policy changes must be submitted to its regulator, Health Canada, which requires a two-year observation period and scientific data proving the new operational orders are safe.

Even in a perfect world, removing the ban completely will be a logistical nightmare. Layers and layers of governance are set up around Canada’s blood supply, making it among the world’s safest, but impeding change.

Canadian Blood Services says it is working towards requesting transitioning the blood band to a one-year deferral period for MSM donors. CBS defines itself as an “independent, not-for-profit organization that operates at an arm’s length from government,” and aims for that change to take effect in 2016.

Besides being discriminatory, the current blood ban places less weight on possible contaminants brought in by heterosexual donors, and ignores the fact that donors of all sexual orientation can lie when filling out the questionnaire. Ultimately, blood testing is the surest way to determine if blood is safe for use.

Last year, CBS reported the rate of HIV detections per 100,000 donations to be 0.4, and the risk of an undetected HIV infectious donation at one in eight million. With current testing methods, CBS says HIV can be detected within one to two weeks of a donor being infected, though CBS cannot fully guarantee against infection through transfusion.