Monday night at Gus' Pub is a quiet affair, though the tables are dotted with tiny beer glasses. Chairs are filled with a mostly hoodie-wearing crowd. The disco twinkle of Christmas lights and the leafy wallpaper transform the stage into a "magical forest," according to comedian Evany Rosen. Other than the VLT-room regulars, everyone else is settled in for a long winter's laugh.

The Halifax Comedy Lounge is a weekly, open-mic stand-up comedy event. Every Monday, eight to 10 brave souls get up on stage for about five minutes each. Some are experienced comedians, testing out material or finding new routes through old jokes. Sometimes travelling comics stop by or, if you're lucky, members of sketch troupe Picnicface, like Rosen or Great Canadian Laugh-off winner Mark Little, are on the bill. Those new to the experience are easy to spot, nervously clutching notes in sweaty palms. But the Comedy Lounge is an ideal place to pop that comedic cherry: A $2 cover buys you an appreciative, easygoing crowd of anywhere from four to 40 people. All you need to do is call ahead to secure a spot.

For the most part, the comedians are a fairly homogeneous group of mostly white, Farrelly-weaned guys in their 20s. Not surprisingly, variations of the same bro jokes dominate (warning: if you're offended by stories of masturbation gone wrong, this isn't your place).

It's usually clear who has spent loads of time on stage, and who's still finding their way. Originally from Vancouver, Ben Mills confidently leans his lanky body over the mike. With a TV-ready voice, he already has that offbeat Comedy Central sitcom thing going on. Marc Hartlen, who comes with a fanbase of friends, flips through a tiny notebook. He finds a joke about the south end creep who was watching women as they slept: "Hey, I'm going to let you finish, but there's a girl next door who's the best sleeper of all time...Wait..." he scratches his head. "This joke's out of date, right?"

"Yeeeah," someone up front acknowledges. There's sympathetic laughter. To his credit, Hartlen quickly moves on to a joke about Whitney Houston's comeback.

More often than not, jokes fall flat, but usually with a gentle tumble rather than a thundering meteor. Over a couple of Monday nights at Gus', there's only one occasion when an audience member booed: right after Comedy Lounge organizer and host Gerry Farmer made an off-the-cuff quip about painful sex with an overweight woman. Bomb.

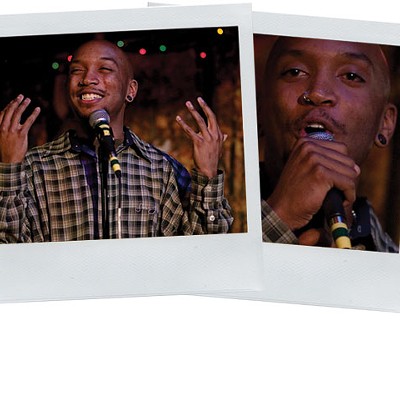

Steve Mackie from Carter Flinn on Vimeo.

But here comes Steven Mackie, yelling "whooo-hoo!" at the crowd like he's the reluctant king of Daytona spring break. The Spryfield telecommunications salesperson appears mild-mannered enough in his tucked-in shirt and sweater, but there's this underlying edge, an off-kilter energy. It spills into his deep drawl—-he could be a voice double for actor Chris Cooper. Mackie is probably the only comedian who can make dead babies and midget porn palatable. (Mackie on Mormon wives: "Four wives? C'mon...You gotta have sex with them all at once. Flapjacks. Four of them stacked up. Four, three, one, two, three. It's like power chords. It's rock 'n' roll!")

Mackie started in 2001 before there were any comedy clubs in town, opening for drag shows at the gay bar, Toolbox. He's one of the hardest working stand-ups—-with a house full of sticky-note jokes, Mackie performs four to five times a week, downtown and around Halifax, often at charity events. He and Kevin Dupuis, a former competitive swimmer from Cole Harbour who does a bizarre scorpion impression, can transform a conventional room of normal, ordinary-looking boys into a volatile place, where anything could happen.

Often, where you'll find Mackie, there's Catherine Robertson. Robertson epitomizes the cool girl from the smoking area: the foul-mouthed tough lass that the boys secretly crushed over, and slightly feared. She puts herself in the middle of her jokes: she's the one making out with the guy on the street, who gets undercut for a sexual favour by a toothless bag lady.

Though she's one of few ladies in the scene, and once was asked by a club to write some "men and women are so different" jokes, Robertson says sexism isn't an issue. "I think that if you felt that was a problem, you wouldn't keep doing it," she says.

Robertson started about three years ago when Yuk Yuk's opened. "I never really thought about it as concretely as I want to be a stand-up, but I always loved comedy." Her first night, she says she was hooked. "I loved it. It's kinda like drugs," Robertson says with a junkie's smile.

There's never been a shortage of funny people in Halifax, longtime home of 22 Minutes, Nikki Payne, Trailer Park Boys. We have the Halifax Comedy Fest. But the local stand-up comedy scene is still in its infancy, at only about five years old.

Paul Ash, a Montreal comedian, moved back to his native Nova Scotia, and started Comedy Dawgs in 2005 at the now-closed Ginger's Tavern, the first regular comedy night that the city had seen in almost 10 years. Picnicface's Mark Little, Kyle Dooley and Cher Hann were all regulars. According to Picnicface's Andrew Bush, who got his hosting job on CBC's Street Cents thanks to a high school comedy set, there was no scene: "With Paul Ash and Comedy Dawgs, people started at zero."

Comedy Lounge's Gerry Farmer also got his start with the Dawgs about four years ago. "I had five or six jokes, that's about two minutes of material," he explains after a show. "Supposed to be about five. I spent the time trying to stretch it out as much as possible."

The call-centre worker and Extreme Championship Wrestling referee (insert joke here) began the open mic night as a charity event for the Metro Food Bank. The Gus' show was so popular, the entrepreneurial-minded Farmer started a regular series. After each Monday he asks the comedians if they want to split the small pot or put it toward marketing and getting a big headliner. But really, Farmer wants to see new faces, especially more black comedians. He's not trying to compete with established comedy clubs like Yuk Yuk's or the new Joker's, both of which have amateur nights. Because having those clubs in town means that comics actually have a shot at getting paid. It's good for everyone.

Besides awesome jokes, Andrew Bush thinks there's a little something intangible that good comedians possess. "You have to like them. It's a little bit like, if you go on stage and if people don't like your jokes it's like they don't like you. They don't like that unchangeable spark that is you."

People adore Peter White. ("How could you not remember me? We dated in my head for six years! You were the first girl I had dream sex with. How could you not remember it? It's weird because I was 13 and didn't know exactly what happened, but I think I was OK.")

He was one of the first comedians on the Dawgs stage, falling into that sweet, baby-faced category. There's something inherently sincere and "everyone's friend" about the guy, who had previously only ever been on stage when running for high school president. Yuk Yuk's gave him their vote: They signed an exclusive deal with White to be his agent and manage his cross-country tours.

White's very first comic experience was in Calgary on his last night of an electrical engineering internship from Dalhousie University. "I just hated everything I was doing, I didn't know anybody. I went to an amateur night and it was just horrible. And so logically I couldn't be any worse."

Within a year White was named one of CBC Radio's top five comics to watch in its "So You Think You're Funny?" competition. He's also one of the only comedians in town who makes a living off it—-he's been a writer on 22 Minutes—-falling back on engineering contracts, if necessary. Summer tends to be a lean time; the comedian's bounty comes in the chilly months. But White's a versatile comedian, willing to tone it down for the slightly older, cover-paying Yuk Yuk's crowd and then raunch it out later at the Comedy Lounge.

Reading the audience and knowing their nasty-talk and F-bomb limits is a skill. Unless you're Bob Saget or Sarah Silverman, often comedians are encouraged to be cleaner. "Usually you can say just about anything. I've learned that any comedy club will pay for any comic," says Farmer. "But a comedy club will pay twice as much for a clean comic."

"I've progressed and gotten cleaner as I've gone along, so take from that what you will," Robertson says, laughing. "In the beginning that's the easiest stuff, it's easiest to get a reaction." What does she find offensive? This one goes out to the ladies: "Females, like honestly, if your joke involves a tampon at this point, I don't want to hear it." Robertson rolls her eyes.

"The only question is, 'Is it funny?'" says Bush. "People ask me what the line is, I think the line is whether people laugh or not. I've heard quote-unquote offensive jokes that are so well-told I'm on board. I've heard comedians tell stories where if you heard that from someone else, you'd think 'oh, good god.' It's amazing Louis CK can say some of the meanest things about his children and you're still laughing. He's incredibly charming and his jokes are really well-formed."

Hecklers aren't exactly the best judge for a joke's success, either. Mackie doesn't worry about them, Robertson's dealt with positive, lecherous male hecklers. Most of the comedians agree that this employment hazard is much more about the person yelling than their own performance. Sometimes hecklers think they're useful sidekicks. Booze doesn't help.

A couple of weeks ago, while hosting the first open mic night at Joker's Comedy Club, Bush received the finger from a loud-talking member of the audience. His astonished expression and sputtering laughter almost made the brief interruption worth the $5 admission.

"Usually I don't mind hecklers," he says later. "Most of the time you don't want one, you want to try out your jokes. But hecklers can sometimes be a gift because the audience is almost always on your side. It doesn't take much to bring a heckler down. You have a microphone and there's tension when a heckler says something, so whatever you say is a release for the audience. They usually laugh.

"I can look at a heckler and say, 'Seriously?' and people will laugh at that one word. I don't worry so much about hecklers."

Not all comedians start their careers in a club. When Ann Denny sits down at the keyboard, she becomes her comedic alias Anna Denova. With all the ditzy confidence and quirkiness of a young Victoria Jackson (the Saturday Night Live 1986-'92 era, before Jackson declared Obama a communist on FOX News), Denny belts out songs about "my stalker and me" and putting on an "emotional condom" for a one-night stand.

Denny is a professional singer and voice coach—-she's only been doing comedy stages for about eight months. A self-proclaimed "unfunny" person, catharticism fuelled her funny flame: Denny had her heart broken by a jazz singer and decided to write a humourous song about it. More of a cabaret performer, Denny initially was shocked by the stand-up comedy scene: "Wow...earlier shows, I'd almost leave, I wasn't used to how in-your-face this was."

She started on stage at the Halifax Comedy Lounge. Then Brian MacQuarrie heard her and invited her to be a guest on Picnicface's show at Yuk Yuk's. Her newbie enthusiasm overflows: "There is a definite sense of community and I was embraced and treated as a colleague as soon as I gave an honest effort at making other people laugh and got some reactions."

Josh Dunn has a long, handsome face, not quite sharp, almost gaunt. He seems quiet and serious and doesn't always look at you directly in the eye, but then will slide in a quick-witted line or joke and peer up, like he's registering the reaction. Awhile back he cut off his long curly hair. But that's probably not what people first notice about Dunn. He has cerebral palsy, a non-progressive condition that limits his physical movement. He uses forearm crutches to get around; it's a bit of a struggle for him to get on the Joker's stage but he manages with a half-crawl and a little assistance. But then he's in his chair, in front of an audience. No notes and completely at ease.

"You know I'm a comic, right? My friends and family want me to do well. They wish me good luck. So what they say is 'Good luck Josh, break a leg...'"

It takes a second for the joke to register, and the audience laughs cautiously. Then he's got them.

But Dunn doesn't entirely play on his disability for laughs. He's much more interested in political comedy, American politics specifically. He's a Stephen Colbert fan.

"Having cerebral palsy is something that's very front-and-centre and visible in my movements," he explains a couple weeks later, over hot chocolate at jane's. "I typically open with it, or have it close to the beginning. 'OK, this is what you see so we'll deal with this.'"

Dunn got his start in comedy in 2006 through a young, savvy employment counsellor, "which is a pretty big joke in itself. Who would not laugh, at least not in your face, at wanting to be a comedian?" Through the open-minded counsellor, Dunn learned about the Comedy Dawgs series.

"A big thing for me was wanting to have an employment situation where I could be my own boss," he says. "Obviously you have to play to an audience and there are the club owners' requests, but there's the freedom to do my own job and one that was creative and artistic."

Of course, getting on stage is nerve-wracking. A perfectionist, Dunn put pressure on himself. "I tried to tell myself the first few times: 'It's just an open mic, in Halifax, in a bar, it's not a huge deal.' But I felt like it was, because I had never done it before, that everyone would be so good."

Turns out Dunn, who was good at presentations in high school and received a scholarship to King's—-"I did well but I was miserable"—-is a comedic natural. The stage came with some unintended benefits. When Dunn was a teenager he suffered from se- vere anxiety and depression. "I would have never been able to do anything like that then because my self-esteem was so low," he says. "Comedy is part of my positive progression. I look at it that way and try and stay away from that dark place as much as possible."

Though his setlist is far from kittens and candy, comedy helps Dunn throw a positive spin on issues. But he also knows that too much happy joy can kill a joke. "I think it was Seinfeld who said you have to have a little bit of healthy anxiety, otherwise you'll be too relaxed and that won't be interesting to anybody."

New comedian Michael Smith knows this fact all too well. Diagnosed as bipolar, Smith took a comedy class through the Healthy Minds Cooperative, a members-run non-profit. Stand Up for Mental Health started in Vancouver as an innovative way for mental health consumers to express themselves. Out of the Halifax workshop a troupe has formed, performing mostly government and corporate workplace gigs.

"We tell jokes about mental health and the medications and, well, being crazy, as a way of empowering, getting over ourselves," says Smith, who refers to himself as Crazy Man. "It's one of the best things that's ever happened to me."

Play "pick out the comedians table." Generally they preside Sopranos style around one table, away from the stage. Sometimes there's quiet talking through the set (they've all heard each others' jokes before), but they're also the loudest laughers, filling up the air that gets sucked out the room when a joke fails. "I like it when the comedians support each other but usually when you hear comedians laugh, the audience isn't laughing," says Bush.

Many of them have toured together, sharing couches and offending other patrons in Denny's restaurants. And there's the drinking, too, a side effect of working in clubs.

"I don't really like drinking scenes in bars," says Dunn, who worries whether being a loner works against him getting ahead. "I'm not condemning anyone by saying that, but that scene, it seems like there's a lot of heavy drinking. I used to do a lot of heavy drinking myself, but I got that under control about a year before I started doing comedy, I wasn't going back there."

His challenges are mostly practical: Though his disability isn't degenerative, he's developed a problem urinating. "Of course, because it's a problem, I have to leave and be by myself. I'm in pain and I have to take care of it. Those issues do keep me out of the scene maybe more than I'd like to."

Where will the scene be in another five years? In 2005, no one could have predicted the impact that a group like Picnicface would have on local comedy, and it's naive to think that these talents will stay here, intact, forever.

"It's funny," says White, "you see people starting off now and they're very Mark Little when they start. He has such a unique style, all across the country, and it's funny to watch now, people starting off trying to do that."

White hopes to split his year by writing for 22 Minutes again, and then touring. But like every other Halifax artist, musician and actor, there is always the taunting lure of bigger cities, like Toronto and Montreal. Catherine Robertson says, "If you take this seriously, you know you're leaving at some point. This is a great town to get started in, but of course you have to leave."

In late October, Josh Dunn took a short trip to Montreal, where Paul Ash is now running comedy nights. Dunn won a contest at a club called Comedyworks. The next night he headlined at the Comedy Nest, inside the old Forum. "I've never headlined a show in Halifax, but my first week in Montreal I got to do one at the old Forum. I think that maybe, where I'm at, perhaps would be more conducive to a larger city," Dunn speculates. "I thought, 'If I can't make it here in this little town, I won't be able to make it anywhere.' But maybe not.'"

There's always south of the border, too: Ann Denny just returned from a successful run of shows in New York. Given her quirky cabaret style, she may find more opportunities on different types of lineups. Then again, she's dating a rancher, so who knows what could happen. Filmmaker/comedian Pardis Parker is currently in Los Angeles (see page 18), one of 13 and the first-ever Canadian selected to participate in CBS' industry comedy showcase.

But whether it's at Gus' or Yuk Yuk's or Joker's, or a new venue, Halifax stand-up has momentum, and it's not going away. Neither will our need to laugh shit out.

"When you think about it," White muses, "it shouldn't work. You shouldn't be able to walk into a room of people and make them laugh. If you tried that on the street, and tried to make them laugh, it just wouldn't work."