What's the definition of "organic?"

If you're like me, you think of "organic" as a series of sustainable agricultural practices—growing food without synthetic chemicals or genetically modified food, and in a way that takes account of the long-term health of the broader environment.

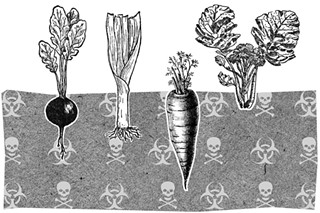

But, I've discovered, when it comes to fertilizer use in Canada, "organic" doesn't mean what we think. And, if the multi-billion dollar fertilizer industry has its way, farmers may soon be using synthetic fertilizers to grow "organic" food.

People are increasingly seeking out organic foods—take a peek inside the crowded courtyard of the Halifax Farmer's Market. But, despite popular demand for organic products, there's been no nation-wide regulatory definition of "organic produce" or "organic meat." To help sort through the confusion, and to ensure consumers know what they're buying, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency is working to create such a definition. "Organic will mean "organic' as certified by the organic standards we're drawing up," explains Michel Saumur, national manager of the Canada Organic Office. "It's a list of specific practices, controls and substances."

The new organic standards will apply to all organic food that is imported from other countries, or that crosses provincial lines. The standards become effective December 14, 2008. But CFIA has an older, existing definition of "organic" as it applies to fertilizers. "Organic fertilizer is defined as "the partially humified remains of animals and plants,'" says Anthony Parker, national manager of CFIA's fertilizer section.

As an example of what confusion might result from conflicting definitions of "organic," Parker points out that manure collected from a typical feed lot—where the cattle are injected with growth hormones and fed genetically modified corn grown with synthetic chemicals—now qualifies as "organic fertilizer."

Such "organic fertilizer," as well as synthetic fertilizers, won't meet the new organic food standards, for obvious reasons. But the fertilizer industry is working overtime to get itself exempted from the new standards.

"They've threatened us," Saumur says of the fertilizer industry. "They want to be exempted. They threaten to write letters to the minister , to the President and Vice-President ." In short, to make life miserable for bureaucrats trying to do good. A demonstration of the fertilizer industry's clout is that the federal Department of Agriculture has spent $707,600 to establish the Canadian Fertilizer Products Forum, whose mission is "to build a national consensus on fertilizer...and advise government on the policy and regulation of fertilizers and supplements." The executive director of CFPF is Clyde Graham, who is also vice president of the Canadian Fertilizer Institute, an industry lobbying group.

"We do have concerns that the standards are not entirely based on science," Graham tells me. "The same basic chemical compounds are found in all fertilizers, and there are some implied claims by organic produce growers that their processes are more environmentally beneficial than the use of traditional products. But the nutrient value is exactly the same."

Graham makes it clear he isn't speaking of manure, which plays a minor role in large-scale agriculture. Rather, he means that completely synthetic fertilizers—made from fossil fuels, usually natural gas—are exactly the same as truly organic fertilizers.

It takes a jaundiced eye to see farm operations as merely the nutrient uptake of plants, disassociated from the web of relationships making up the natural world.

But if the fertilizer industry successfully gets itself exempted from the new organic regulations, that's what "organic" will mean in Canada.

Send your pure, wholesome feedback to [email protected].