This is a story about a man and an idea, an idea that became a story, a story that became a media circus and the important issue that got lost in all of that.

We'll start with the man.

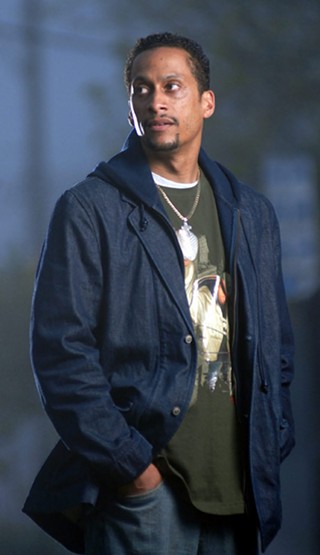

Physically, Wade Smith towers an inch taller than the six feet St. Francis Xavier University's online statistics boards claim he is. St. FX is where Smith played basketball and set records as an undergrad. These days he's approaching 40, but when he's not wearing his suit at work, you'll still often find him dressed in a track suit and carrying a large gym bag on his way to, or from, the basketball court.

He's confident, comfortable in his own skin. He often sports a gold Nefertiti pendant, a gift from his mother, a connection he says makes him think of "mother earth, the power of the black queen, all that wonderful stuff." His handshake is firm and he looks directly into your eyes when he speaks. He has no trouble in speaking his mind. His words spill out in complete, coherent thoughts. He's a bit cautious around the press. But then, he's learned to be.

You know his name. If you go to St. Patrick's High School, you know him as vice-principal Smith. If you frequent the Gottingen Street Y, where he once played basketball and now coaches, you know him as Mr. Smith, or maybe just Wade. If you read the newspapers or listen to the CBC, however, you might know him as the African Nova Scotian teacher who, last year, floated the idea of an all-black school.

The idea isn't new. It isn't even Smith's. But it is worth talking about.

Which brings us to the story.

In late April, 2006, Wade Smith was in his office in the decaying building that is St. Patrick's High School at Quinpool and Windsor, when he got a call from a former student who'd become a CBC radio reporter. Maggie Rahr was interested in Smith's reaction to the release of a new report criticizing Halifax Regional School Board for its "modest steps" in responding to the challenges African Nova Scotian students face.

We'll get to Smith's reaction, but to better understand it, we need to look further back. Thirteen years or so.

In 1994, the Black Learners' Advisory Committee submitted a landmark report to the province on the challenges faced by African Nova Scotian youth, including documenting the province's sorry history of separate, segregated, underfunded black school boards that existed in the province into the 1950s. It recommended that "African Nova Scotian children must be given the opportunity to experience an appropriate cultural education which gives them an intimate knowledge of, and which honours and respects, the history and culture of black people." The report makes a number of suggestions on how the situation for black learners could be improved, including what it called an "Afrocentric Learning Institute," imagined as a resource centre to assist in curriculum development. The report recommends changes to teaching materials and the role of the Nova Scotia government, community involvement, and advocacy for both teachers and parents.

But change is slow to come. It wasn't until 2001 that an African Nova Scotian Advisory Committee was formed at the school board. The committee made a series of 22 recommendations in October 2002, looking at what had been done since the 1994 BLAC report, reiterating some of its suggestions and adding new ones. They included position papers, sensitivity training for teachers, mentoring opportunities and developing cultural communication strategies.

Forward to April 2006. School board member Doug Sparks and the African Nova Scotian Advisory Committee presented a new report to the board which showed just how little had been accomplished—of the 22 recommendations made in the October 2002 report, two were implemented, 13 partially acted upon and seven ignored. The 2006 report criticized the school board for failing to adequately address the challenges faced by African Nova Scotian learners, citing as evidence "comparative drop-out rates, school suspension rates, graduation rates, academic averages achieved" and the less tangible but no less important "feelings of alienation" felt by both black students and their parents.

Wade Smith was a logical person to talk about the report. He's a black Nova Scotian educator who grew up in Halifax's north end and became a vice-principal at St. Pat's, a small, 400-student high school attended by many members of the inner-city black community.

Rahr thought so, too. "I knew Wade and I thought he could say something a little more reflective and true." Not that everyone agreed. "To be honest," she says now, "when I said I wanted to do this story said, "That's old, it's not news.' I was like, this is obviously a huge deal."

Smith was happy to oblige. "Data is the one thing in society that doesn't lie to people," he told her of the numbers in the report. "People do stand up and pay attention when they start to see numbers." He was thinking as he talked. "Maybe it's time for a change," he said at one point. "Maybe we need to look at an all-black school or other alternatives."

Rahr was intrigued. "An all-black school? What do you mean?"

"Well, you know... something other cultures are doing when they come to Nova Scotia. They have economic independence, they care for their culture, they invest in it, it enhances students as they go through life. It allows them to keep connected, but also go though the mainstream education system." He let that sink in, then added, "It's something that we need to be thinking about if we're truly thinking about doing what's best for our kids."

"Can I quote you on that?" Rahr asked. She wasn't thinking of it as a sensational story, just a really interesting, important one. "I have so much respect for him for coming out and saying that," says Rahr, now a reporter on News 95.7 Halifax. "I really wanted to handle the story with care and respect. I think he's got a lot of integrity."

And that was all there was to it.

Rahr's minute-and-a-half news report ran on the CBC the day after she and Smith spoke. The producers of CBC Radio's Information Morning invited him to come on the show to elaborate on his comments the next day. "Putting forward the notion of a black school is something people might not be comfortable with," Smith acknowledged, "because it suggests that things aren't working." But Smith himself tried to cast the issue in a different light. "I think you have to look at the possibility of a black school as something positive, that's good for our culture and good for our people."

And that's when it all hit the national media fan and the circus came to town. By that afternoon, Smith was getting calls for interviews from as far away as British Columbia. The Globe and Mail called. CTV interviewed St. Pat's students on how they'd feel about going to an all-black school.

Though not all the resulting articles were inflammatory, many reporters took the idea of separate, segregated schools and looked for educators and politicians inside and outside the black community who would speak out against the idea of an all-black school. They weren't hard to find.

Patrick Kakembo, the director of African Canadian Services in the Nova Scotia Department of Education, was among the more rational. He said there is no evidence to say an all-black school would do anything but exacerbate existing problems by "cocooning" African Nova Scotian learners and not preparing them for life and employment in a global culture. "The have to compete with other people. The days of separate education are over," he said, mentioning that black cultural studies already exist in many Nova Scotia schools.

Barry Barnet, the white cabinet minister for African Nova Scotia Affairs, said he didn't think "a segregated school" was necessarily the solution to the problems Smith was trying to address.

The most prominent media opponents of the idea suggested separating white and black learners was itself racist and counter-productive, especially after the long struggle to integrate Nova Scotia's education system. Editorials suggesting an all-black school would be tantamount to a return to those days ran with headlines such as "A Step Back?".

Posts in local online discussion groups were more scathing, branding Smith's suggestions "ignorant." But it got worse. An American white supremacist site picked up the story and used it to garner support for segregating black students.

Alex J. Walling's commentary on halifaxlive.com was entitled "No, No, No to Black Schools," in which he dismissed the findings of the BLAC report, suggesting the real problem is a lack of cultural assimilation into society, and wondered, "if we ever get to a black school, what's next? A black Wal-Mart? A black Tim's?"

The media firestorm seemed to ignore what was partly a case of semantics. The word "segregation" speaks to the history of black education in North America, where, until quite recently, white school boards' mandate was oppression, physically excluding black learners from the schools the white kids went to. All-black and Africentric aren't synonymous with segregation. They can mean something quite different: Focused education for black children to help them feel pride in their history and culture along with an effort to distribute funding to where it's needed, some of the things first suggested in the 1994 BLAC report.

Smith was very concerned the controversy might bleed into the classroom. "I went into a lot of classes and made sure I clarified some of the things," he says, to "make sure that as vice-principal who is responsible for the alphabet from L to Z that didn't mean I was only responsible for kids of colour—I'm responsible for all kids. I needed to put some fears at ease and explain a few things to young students."

For Smith, the issue is not about separating the races so much as it is about preserving culture. "We don't bat an eye if someone Jewish builds a new institution or a temple goes up. Greeks, Italians, they come from different conditions than African Nova Scotian people, but they come with a purpose trying to hold on to what is theirs and we respect that. Had I been a native man that proposed this, maybe it would have been applauded. I think there's a very serious racial undertone that people continue to downplay that made me a little defensive."

He remains unrepentant. "For me to sit here and tell you why we need it is for you to explain to me why we don't need it. We have kids dropping out at a high rate, kids are unsuccessful, they're not doing well at school, they're struggling. I don't understand why I'd have to explain to you why the enhancement of culture in the educational setting would be good. It's about improvement, growth, it's about self-esteem, all the things I thought education was about, for me personally."

If we're going to understand what's really going on here, perhaps we need to circle back to the man himself. Who is Wade Smith? Why would he speak his mind and risk his reputation?

Wade Smith was born on Creighton Street and grew up on Bauer Street. His father Bobby was "a postman, a bartender and an umpire," and his mother Muriel a clerk, until a back injury made her a stay-at-home mother.

Smith was the youngest of five, with three older brothers and a sister. Smith's brother Robert Mark was a fast-pitch softball star and coach, and is in both the Canadian and American Softball Halls of Fame. His brother Craig Marshall was a classmate of poet George Elliot Clarke's at Queen Elizabeth High School in the late '70s. Craig went on to become a corporal in the RCMP and is the author of a number of books, including Journey, an African Canadian educational resource guide, and the recently published history of black officers in the RCMP, You Better Be White By 6am.

Wade Smith's best friend growing up was Augy Jones, the son of local lawyer and civil-rights activist Burnley "Rocky" Jones. They were classmates and teammates; they played mini-basketball at the Community Y and continued to play together all the way through school at St. Francis Xavier. Augy Jones also went into education and is now a teacher in the Bahamas.

Captain or co-captain of virtually every team he played on, Smith won a number of provincial championships in high school and spent three years with the junior national team. He credits his basketball mentors as well as his family with not only giving him strength and values as a young man, but also eventually leading him into teaching.

"All the mentors in my life had very high expectations of the core group of young men I grew up with," he says. "All of them saw beyond basketball. They said, we can work on our game, but that's not why you're here. You're here to develop character, you're here to understand what it means to be a young man. If you realize people put expectations of you that you can live up to, think what happens when you reach them."

Bev Greenlaw, who coached the Nova Scotia Men's basketball team to gold at the 1987 Canada Games, describes Smith as a low-key, amiable sort of person—with purpose. "If I had one word for Wade and his entire family, it would be "character.'" Greenlaw is married to Sylvia Hamilton, a teacher at the University of King's College and a filmmaker, in the midst of developing a one-hour documentary about Canada's history of segregated schools called The Little Black Schoolhouse. She's saving her thoughts on black education for the film, but of Smith she will say what's important to know is "how bright and thoughtful he is, and the way things were reported didn't reflect the level of measured thought about the things he might have said."

After graduating from Queen Elizabeth High, where he says he has nothing but good memories—"I remember QE being populated by lots of Greek kids, Italian, black and white kids, the rich and poor" —he studied English and psychology ("I've needed them both along the way") at St. FX, and then education at Saint Mary's.

He began his teaching career at Weymouth Consolidated in Weymouth, before moving on to stints at Sackville High and in Cole Harbour before arriving at St. Patrick's 10 years ago.

Smith just recently finished being a student himself. On May 11, he completed a master's degree through Mount Saint Vincent University. Though he changed its focus to autoethnography—writing about the self analytically—his original subject of study was hip-hop music. "It's fraught with genius, and traditional education doesn't want to admit it. Teachers don't realize that when they are addressing a class of kids, they are in the midst of hip-hop intellectuals. The toughest thing is combatting the small stream of what people get of hip-hop that's extremely negative. It fuels the passion of trying to get the word out that it's not everything you think it is." Smith and his family live in Beechville Estates. "I'd love to get downtown, back to the north end but damn, it's awfully expensive to live in the north end of Halifax," he says. Nonetheless, the north end Y is still Smith's community YMCA.

Shawna Wright, the managing director at the Y, knows the Smith family well. Thane, another of Wade's brothers, also volunteers with him as a basketball coach. "He's real. He's one of the most honest people I've met," she says of Wade. "I trust his opinion, and it's not just him, it's his wife, too." (Smith's wife Sherry is a parole officer and they have two sons, Jaxon and Jaydan, ages five and eight.)

Darnelle Beals, 20, was a St. Pat's student, and knew Smith as both a teacher and a vice-principal. He works at the Y as well. He gets very serious when he speaks of Smith, and his eyes focus on a point in the distance as he explains why he sees Wade Smith as a role model. "He can relate to everybody. He loves kids, he loves to make people laugh," says Beals. "That's the kind of person I want to be, just like that. When you're on your best behaviour he still talks to you, because he doesn't want you to fall." Beals sees Smith's influence on kids at both St. Pat's and at the Y. "It wasn't only me he helped. It's not just blacks, it's every race. It was more the kids out of his community that he got closer to because we all know that we can talk to Mr. Smith. The people that aren't in his community don't know him that way."

Which tells you something about Wade Smith, the person. What about the idea?

The idea of an all-black school is controversial, but it isn't completely unheard of. Or entirely untried.

At Brookview Middle School in the Jane & Finch area of northern Toronto, a school with a roughly 50 percent black student population, an Africentric social studies program has been in the works for the better part of a year, and is expected to be implemented in September 2007. The curriculum, funded by the city, will be instituted in grades 6, 7 and 8, and taught to all students. They will learn about black artists, politicians and the history of black immigration to Canada. (The word "Africentric" has been chosen to denote this Canadian approach, as opposed to the American "Afrocentric," which is seen to be less inclusive of other cultures.)

The program has been developed in response to poor academic performances by black learners and is being overseen by Lloyd McKell, the executive officer for student and community equity at the Toronto District School Board. When McKell was quoted in a September 2005 Toronto Star story as being "in favour of creating a black-focused school as a pilot project for black teens on the brink of dropping out," the charges of racism levelled at him in the Toronto media mirror what Wade Smith had to go through. He's quoted in a story in the University of Toronto newspaper The Varsity on the same subject: "A black-focused school concept is not a skin pigmentation issue. This is not the segregation of black-skinned students from white-skinned students. how institutional or systemic racism currently operates in our city, its effect upon people, and about how racism acts to preserve inequity among people in our society."

We needn't even look as far as Ontario to see where the black community has tried to take steps to help its own. The Nelson Whynder Elementary School in North Preston is an "African-centric" school that last year had an enrolment of 120 children, almost 100 percent African Nova Scotian. Its mission statement speaks of fostering "respect and understanding of our culture and heritage, while developing each learner to their full physical, social and academic potential...in partnership with the community." Acting principal Carolyn Taylor refuses to label the curriculum Africentric, instead saying the education there is "family oriented. Children can learn about their culture in their own community, to draw upon the expertise of their elders."

Last June, a roundtable took place at Dalhousie on the "Current Social and Political Struggles of the Black Community in Canada," hosted by the Trudeau Foundation. It featured three African Nova Scotian community leaders: George Elliot Clarke, Sylvia Hamilton and Rocky Jones. About halfway through the discussion, Jones said he thought the political and socioeconomic situation for African Canadians was worse now than it has been in 40 years. He urged people to talk about things, to get organized and to speak out. Words such as "militancy" were expressed.

When hearing of Jones's comments, Smith doesn't disagree. "Everything comes down to education. You need to have people around that are open to seeing this is how it is for certain groups of people in our society. It's painful. I'm not going to harp on it, but I'll tell you it's real, and I'm going to move forward in it. A lot of people don't want to be real, a lot of people in the educational process of race issues, of sexuality issues, of gender issues, they don't want to be open to hearing it."

Doug Sparks, the former African Nova Scotian representative on the Halifax School Board, says there wasn't enough discussion about Smith's ideas when they were originally tabled. "There needs to be a debate within the community," he says. "But before there's even a debate, it's been already condemned without anybody really knowing what he was trying to say. He was already judged. Who do you put the blame on? Wade has been the conduit for that particular issue. What Wade was really trying to say is: What we are doing now, is it working? We need to look at alternatives. He suggested that this be one of the alternatives."

Sparks isn't the only one who believes Smith was misunderstood. "It was such a small article in the beginning, you couldn't get a sense of what he really meant," says Doug Earle, the acting executive director at the Black Educators Association. As a former principal at Joseph Howe Elementary, he feels there are things that can be done to improve the system as it already exists, but wasn't surprised when Smith offered up an alternative perspective. "Sometimes you look at where you're working and you may have a different idea of what might work."

Edy Guy-Francois is the former principal at Caledonia Junior High in Dartmouth, where she worked for seven years before retiring last June. It is a school with an approximately 12 percent African Nova Scotian population. She says the furor that was raised when Wade Smith went on record was due to his "admitting the system is failing people, and if you say that you have to look at the reasons why it is." Though she says she "thought that he was pretty brave to go way out on that limb," Guy-Francois suggests that a separate school wouldn't be necessary if more money went towards fostering Africentric learning in the existing schools. "The school board put money out there for French immersion, they could put money out there for other forms of education," she says.

Though she points out there simply isn't the economic base in the community here to fund a private all-black school, what about the existing black cultural and historical programs in the public school system? "I know there are programs operating in high schools...it's a beginning," she says, guardedly. And on the subject of Smith and the media glare, she adds, "He was out of the gate before he really had an opportunity to formulate everything he wanted to say, and then everyone was jumping on him for what they heard, and I'm sure with all the pressure that went with that he still wasn't able to clarify."

What would he clarify if he could?

Smith is nothing but grateful when he thinks about the opportunities he's had, but is unreservedly angry at some of the terms that were bandied about concerning him and his ideas, terms that suggest he is disrespectful of the school and people he works with, something he says couldn't be further from the truth. "Using terms like segregation, anyone who knows me knows the diversity that's affected my life. It would be hypocritical to say that, given my upbringing and the people in my life who I call my friends. It would be a slap in the face to every colleague I've ever had."

He adds that societal issues have come into high schools with teachers and administrators not necessarily prepared to deal with them. "That encompasses a lot of things: young people snubbing their nose at the Young Offenders Act, older people who take advantage of younger people in the drug trade, kids at 15 and 16 getting fed up with mom and dad, coming to the school and going through social assistance and moving," he says. "You take a look at all those issues, they're not for any one group of people in the school. They effect every student from every walk of life, from every socio-economic background, but I think those issues hit marginalized students a hell of a lot harder than they do students who have means."

It's been over a year since Wade Smith's name was in newspapers across the country. The media has moved on, chasing fresh stories. In a recent editorial in the Daily News entitled "High schools need more like Smith," Alex J. Walling, having heard Smith speak at the Nova Scotia School Athletic Federation 10th annual Celebration of Sport dinner, devoted the entire piece to Smith, calling him "a black educator, a terrific role model and a fine human being," adding, "All kids, inner city, black, white or whatever, could benefit from Smith."

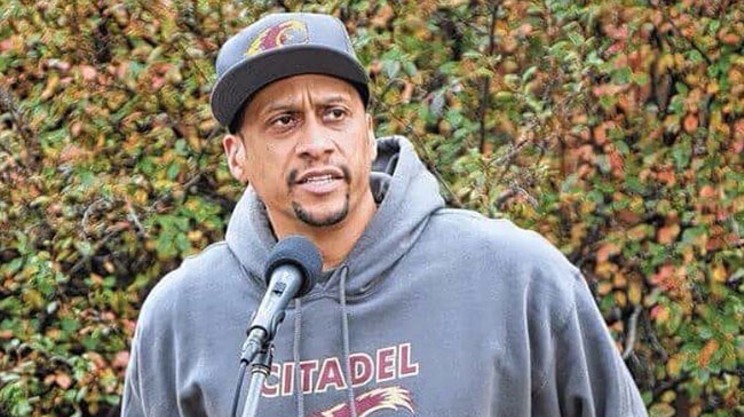

The crumbling St. Pat's campus is in its final weeks as a learning institution. Its student body will be headed to the new Citadel High campus just up the road, now well on its way to being completed. The St. Pat's students will be merged with those from Smith's alma mater, QEH. Smith will be one of three vice-principals at Citadel, though he hasn't had much time to be excited about it just yet. "It's a busy time right now, you don't have the time to reflect. We're closing one building with a tremendous history and that's very exciting unto itself." He refuses to speculate on any potential downside to a larger campus, one that merges two student populations. "I won't spend any energy worrying about things that might happen. I will meet any concerns with a tremendous amount of positivity with a new experience, with the new students."

Smith is philosophical as he reflects on the kind of attention speaking his mind has earned him. "I didn't lose any friends and I didn't gain any friends, but you do end up standing alone. It just goes to show that the subject is still taboo in Nova Scotia. I still struggle with the fact that I think what I said wasn't all that powerful.

"I've come to realize that the one thing I said that was most inflammatory was "all-black.' I am convinced on a certain level, and this is from speaking to students after the fact, it's strange when you say all-black instead of Africentric Learning Institution, ALI. If you say that, well, that's great, that's a really good idea. Ultimately I don't think I would have gotten any media attention if I'd said Africentric. Part of me was a little shocked that people were so far gone in their thinking."

In the end, Smith doesn't really regret what happened. "If people are talking about it, it's a good thing," he says. "Ultimately, education is what I do."

Frequent Coast contributor Carsten Knox was educated in the American International school system, where he had a broad range of learning, but not much of a Canadian perspective. In American history books, the USA won the War of 1812. Just so you know.