Don’t let the plot fool you: Splinters is not based on a true story. It’s just a story that happens to be true.

“The actual events of the play are not autobiographical,” insists playwright Lee-Anne Poole. “Besides the fact that, you know, I have experienced some of them.”

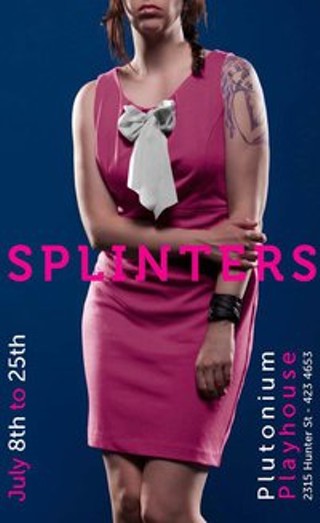

She calls Splinters, opening at the Plutonium Playhouse (July 8-25, Tuesday-Sunday $15-$20, 423-4653), a “fortune-teller” for her life: it’s about a lesbian, Belle, who has secretly been dating a man for over a year. Poole, who until recently considered herself a lesbian, began writing the play years ago while dating a woman. It was only after finishing both the script and relationship that she too began seeing a man—-and, like Belle, it’s been over a year. “I’ve been thinking a lot about the validity of sexuality and how much people’s identity relies on that,” Poole says. “I felt like I was betraying or hiding a side of myself when, suddenly standing next to a man, you’re automatically assumed totally straight.”

That’s Belle’s problem in Splinters. Prompted by her father’s death, Belle returns to visit her mother in Sambro, Nova Scotia (where Poole’s own mother lives—-still not autobiography, though). Belle brings her beau, but she hides their romance from her mother, worried about proving her right—-maybe the whole “lesbian thing” was just a phase after all. “It’s less about just blanketed homophobia,” Poole explains, “and more about where I think sexuality is going, where sexuality is splintering off, and it doesn’t so much matter whether you’re straight or gay or bi, and people are just attracted to people.”

Maybe that’s why it’s so easy for straight folk to (mostly) fill the production. Three out of the show’s four actors are straight (including Stephanie MacDonald as Belle), as well as the director, Simon Bloom.

“Ultimately, whether or not it is a play about sexuality, it is a play about human beings,” Bloom says. “Not being able to be heard and not being able to be understood is something that people experience regardless of sexuality.”

That’s why Bloom finds it so easy to bring out other themes in the play, like what he calls the show’s “undercurrent of scopophilia.” Imagine, onstage, walls of a house made of long, broken-up pieces of thin wood, and characters shadowed in the background, watching the action before them.

“It’s still a naturalistic play,” Bloom says. “It just has elements of storytelling that are not naturalistic.”

Call it naturalistic if you want. Poole prefers to call the style one “where things are shitty and hard and they suck, but lots of funny stuff happens.” In summary: “It really is just real life.”

Just not her life. Sort of.